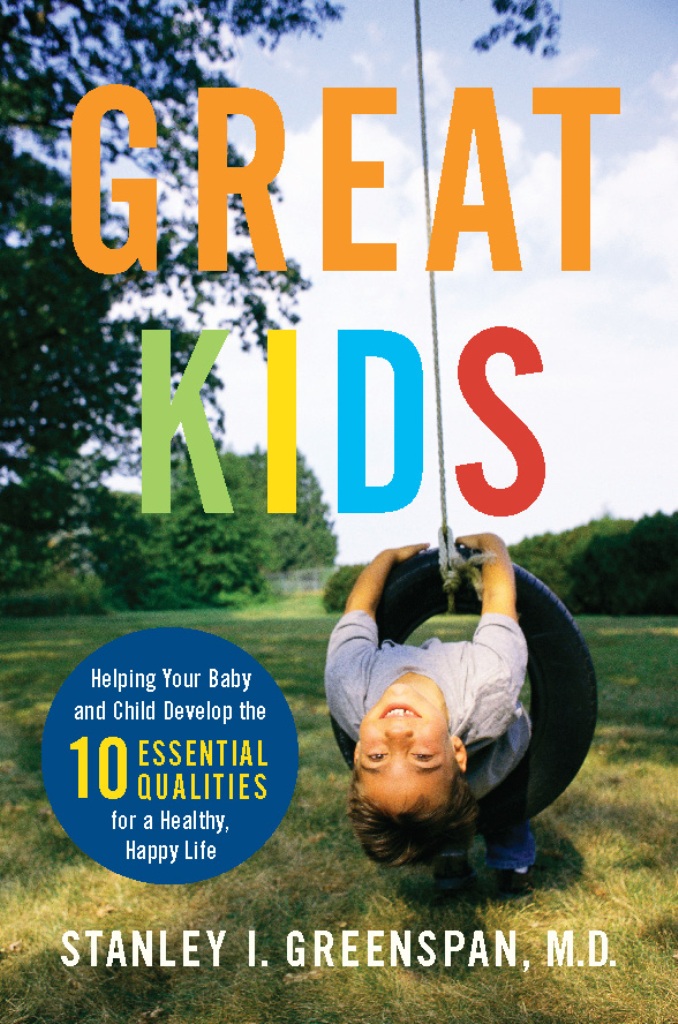

Great Kids

Helping Your Baby and Child Develop the Ten Essential Qualities for a Healthy, Happy Life

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$12.99Price

$16.99 CADFormat

Format:

ebook $12.99 $16.99 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 10, 2007. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Parents all over the world have certain universal aspirations. They want their children to contribute meaningfully to society and to pursue their own dreams. But we appear to be missing the essentials. In this inspiring book, based on 30 years of research and practice, Dr. Stanley Greenspan redefines the qualities of an emotionally and intellectually healthy child and identifies the ways that parents can help their children develop each quality. The qualities that make us call a child a “great kid,” such as empathy, curiosity, and logical thinking, are fundamental and underlie all the academic, athletic, and social talents that a child might develop. We are not born with these traits, Greenspan demonstrates, they come from experience, which suggests that each and every parent can encourage them and that each and every child can strive to acquire them.

Series:

- On Sale

- Sep 10, 2007

- Page Count

- 240 pages

- Publisher

- Da Capo Lifelong Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780738211763

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use