Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

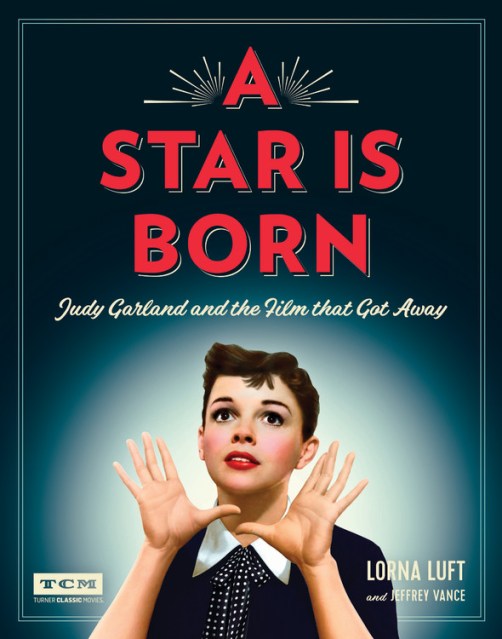

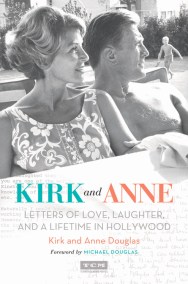

A Star Is Born

Judy Garland and the Film that Got Away

Contributors

By Lorna Luft

By Turner Classic Movies

Formats and Prices

Price

$28.00Price

$36.50 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $28.00 $36.50 CAD

- ebook $14.99 $19.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 18, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

A Star Is Born –– the classic Hollywood tale about a young talent rising to superstardom, and the downfall of her mentor/lover along the way — has never gone out of style. It has seen five film adaptations, but none compares to the 1954 version starring Judy Garland in her greatest role. But while it was the crowning performance of the legendary entertainer’s career, the production turned into one of the most talked about in movie history.

The story, which depicts the dark side of fame, addiction, loss, and suicide, paralleled Garland’s own tumultuous life in many ways. While hitting alarmingly close to home for the fragile star, it ultimately led to a superlative performance — one that was nominated for an Academy Award, but lost in one of the biggest upsets in Oscar history. Running far too long for the studio’s tastes, Warner Bros. notoriously slashed extensive amounts of footage from the finished print, leaving A Star is Born in tatters and breaking the heart of both the film’s star and director George Cukor.

Today, with a director’s cut reconstructed from previously lost scenes and audio, the 1954 A Star is Born has taken its deserved place among the most critically acclaimed movies of all time, and continues to inspire each new generation that discovers it. Now, Lorna Luft, daughter of Judy Garland and the film’s producer, Sid Luft, tells the story of the production, and of her mother’s fight to save her career, as only she could. Teaming with film historian Jeffrey Vance, A Star Is Born is a vivid and refreshingly candid account of the crafting, loss, and restoration of a movie classic, complemented by a trove of images from the family collection taken both on and off the set. The book also includes essays on the other screen adaptations of A Star Is Born, to round out a complete history of a story that has remained a Hollywood favorite for close to a century.

Genre:

-

"A Star is Born: Judy Garland and the Film that Got Away is delightfully full of back story for the first four versions. Ms. Luft and Mr. Vance began their collaboration in 2010 and clearly did all it took to get the final product, a gem for Judy Garland fans, as well as for film buffs and Hollywood aficionados. This semi-biographical book is everything you'll ever want to know about Garland's 1954 version but never thought to ask.New York Journal of Books

- On Sale

- Sep 18, 2018

- Page Count

- 248 pages

- Publisher

- Running Press

- ISBN-13

- 9780762464814

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use