Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

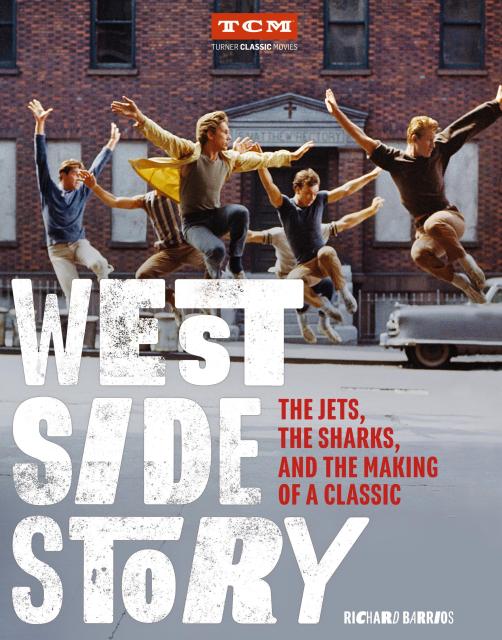

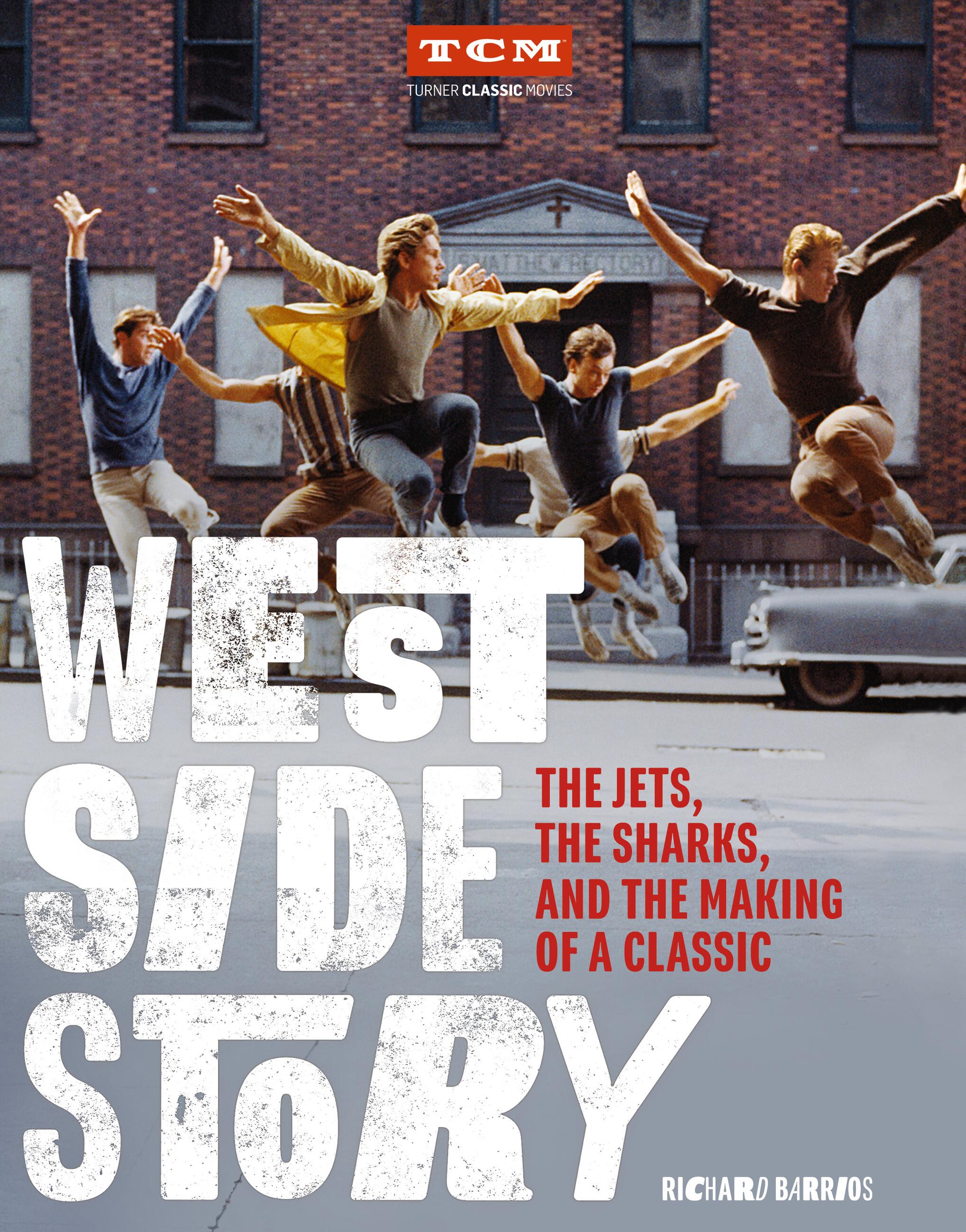

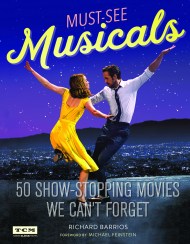

West Side Story

The Jets, the Sharks, and the Making of a Classic

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Jun 30, 2020

- Page Count

- 232 pages

- Publisher

- Running Press

- ISBN-13

- 9780762469482

Price

$28.00Price

$35.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $28.00 $35.00 CAD

- ebook $14.99 $19.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around June 30, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

A major hit on Broadway, on film West Side Story became immortal-a movie different from anything that had come before, but this cinematic victory came at a price. In this engrossing volume, film historian Richard Barrios recounts how the drama and rivalries seen onscreen played out to equal intensity behind-the-scenes, while still achieving extraordinary artistic feats.

The making and impact of West Side Story has so far been recounted only in vestiges. In the pages of this book, the backstage tale comes to life along with insight on what has made the film a favorite across six decades: its brilliant use of dance as staged by erstwhile co-director Jerome Robbins; a meaningful story, as set to Leonard Bernstein and Stephen Sondheim’s soundtrack; the performances of a youthful ensemble cast featuring Natalie Wood, Rita Moreno, George Chakiris, and more; a film with Shakespearean roots (Romeo and Juliet) that is simultaneously timeless and current. West Side Story was a triumph that appeared to be very much of its time; over the years it has shown itself to be eternal.

Series:

-

“Informative and engaging”The Washington Post

-

"Informative and engaging"The Washington Post

-

"While remaining always respectful to the movie and the people who made it, the author lays bare the behind-the-scenes tumult, elevating the book from a typical making-of story to something really special: a no-holds-barred chronicle of what it really takes to get a great movie made."Booklist starred review

-

"In this engrossing volume, Barrios recounts how the drama and rivalries seen onscreen played out with matched intensity behind the scenes, yet still managed to result in an artistic feat."Publishers Weekly

-

“In this engrossing volume, Barrios recounts how the drama and rivalries seen onscreen played out with matched intensity behind the scenes, yet still managed to result in an artistic feat.”—Publishers Weekly

-

"Barrios has a way with words and his elegant turn of phrase along with his thoughtful and informed insights make this a thoroughly enjoyable read. ... This the perfect gift for the West Side Story fanatic in your life. ...an engrossing read."Out of the Past blog

-

“Barrios has a way with words and his elegant turn of phrase along with his thoughtful and informed insights make this a thoroughly enjoyable read. … This the perfect gift for the West Side Story fanatic in your life. …an engrossing read.”Out of the Past blog