By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

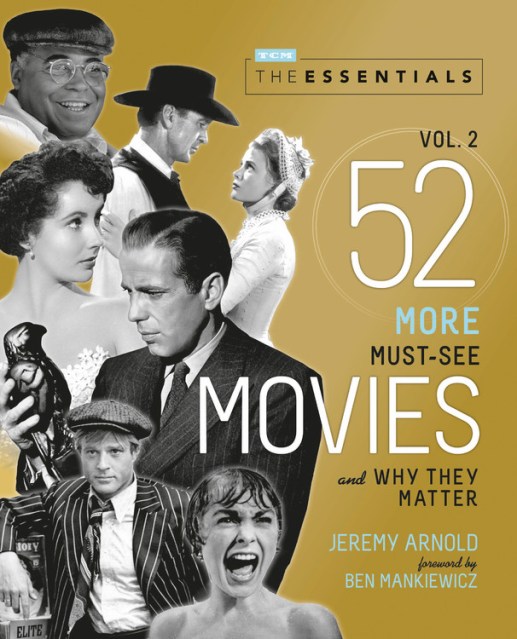

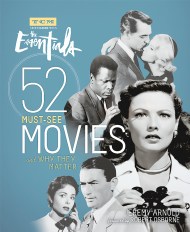

The Essentials Vol. 2

52 More Must-See Movies and Why They Matter

Contributors

Foreword by Ben Mankiewicz

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Oct 20, 2020

- Page Count

- 312 pages

- Publisher

- Running Press

- ISBN-13

- 9780762469390

Price

$25.99Price

$35.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $25.99 $35.99 CAD

- ebook $13.99 $17.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 20, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Since 2001, Turner Classic Movies’ The Essentials has been the ultimate destination for cinephiles showcasing films that have had a lasting impact on audiences and filmmakers everywhere. Enjoy one film per week for a year of stellar viewing or indulge in your own classic movie festival. Spanning the silent era through the late 1980s with such diverse films as Top Hat, Brief Encounter, Rashomon, Vertigo, and Field of Dreams, it’s an indispensable book for movie lovers to expand their knowledge of cinema and discover or revisit landmark films that impacted Hollywood forever.

In this second volume based on the series, fifty-two films are profiled with insightful notes on why they’re Essential watches and feature TCM’s Ben Mankiewicz and the late Robert Osborne, as well as Rob Reiner, Sydney Pollack, Molly Haskell, Carrie Fisher, Rose McGowan, Alec Baldwin, Drew Barrymore, Sally Field, William Friedkin, Ava DuVernay, and Brad Bird.

Series:

-

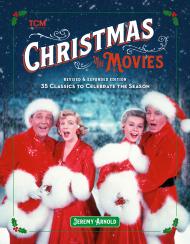

“Film historian and author Arnold (Christmas in the Movies) returns for a second bite at the classics apple with this delightful sequel to 2016’s The Essentials: 52 Must-See Movies and Why They Matter… Arnold’s knowledge is vast, and the joyful tone of his sprightly writing is infectious. With a foreword by current TCM host Ben Mankiewicz, an index and an extensive bibliography, and a list of all the films screened on The Essentials, this book will please film buffs of all ages and levels of cinema knowledge.”Library Journal starred review

-

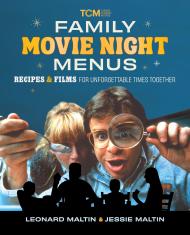

"As in the first collection of essays, Jeremy Arnold provides background information and perspective on each title, while the publisher frames all of this in a handsome package with carefully-chosen stills....You can't go wrong revisiting any of [these] movies and you'll enjoy rekindling thoughts and memories of them in this appealing and well-written survey."Leonard Maltin, film critic and historian

-

“Lavishly illustrated and intelligently written… The new Volume 2 handsomely complements Volume 1 design-wise and sits neatly on the shelf beside its older brother.”Raymond Benson, Cinema Retro

-

“A clear and concise breakdown of why these movies are worth your time… This is the perfect gift for someone that wants to get into classic movies but has no idea where to start.”Journeys in Classic Film

-

“A sequel that is better than the original.”DVD Corner

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use