By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

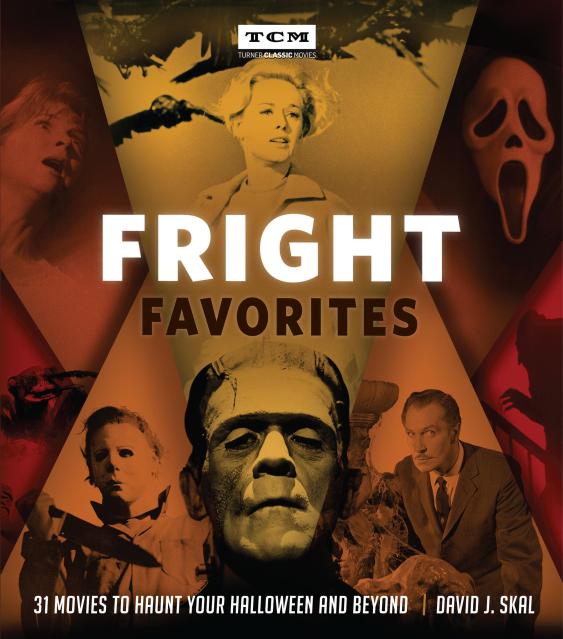

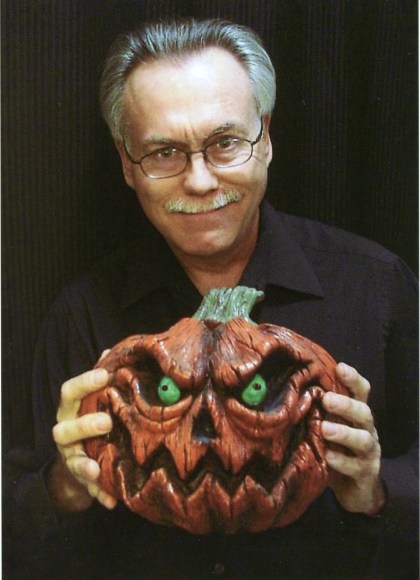

Fright Favorites

31 Movies to Haunt Your Halloween and Beyond

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Sep 1, 2020

- Page Count

- 224 pages

- Publisher

- Running Press

- ISBN-13

- 9780762497621

Price

$24.00Price

$30.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $24.00 $30.00 CAD

- ebook $12.99 $16.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 1, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Turner Classic Movies presents a collection of monster greats, modern and classic horror, and family-friendly cinematic treats that capture the spirit of Halloween, complete with reviews, behind-the-scenes stories, and iconic images.

Fright Favorites spotlights 31 essential Halloween-time films, their associated sequels and remakes, and recommendations to expand your seasonal repertoire based on your favorites. Featured titles include Nosferatu (1922), Dracula (1931), Cat People (1942), Them (1953), House on Haunted Hill (1959), Black Sunday (1960), Rosemary’s Baby (1968), Young Frankenstein (1976), Beetlejuice (1988), Get Out (2017), and many more.

Genre:

Series:

-

"Fright Favorites is like the full-size candy bar in your trick-or-treat bag: it's small enough to hold in one hand, delicious, and is written in digestible, bite-sized sections so that you can savor it or eat read all of it in one sitting!...From its menacing black and orange cover to its full-color end papers featuring horror movie posters, David J. Skal's Fright Favorites: 31 Movies to Haunt Your Halloween and Beyond is a seasonal treat that horror and classical film fans will want to keep on their coffee tables all season long."Ally Russell, Out of the Past Blog

-

"An essential book especially for those just starting their journey into horror movie history."Reviews Coming at YA

-

"Turner Classic Movies presents a gorgeous coffee table style collection of modern and classic horror that captures the Halloween spirit. It's full of curated images, reviews, and behind-the-scenes stories to expand your annual Halloween viewing horizons."Bloody Disgusting

-

“I must say that Fright Favorites is almost a perfect list of films that could easily serve as a haunted advent calendar to count down to Halloween.”Waylon Jordan, iHorror.com

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use