Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

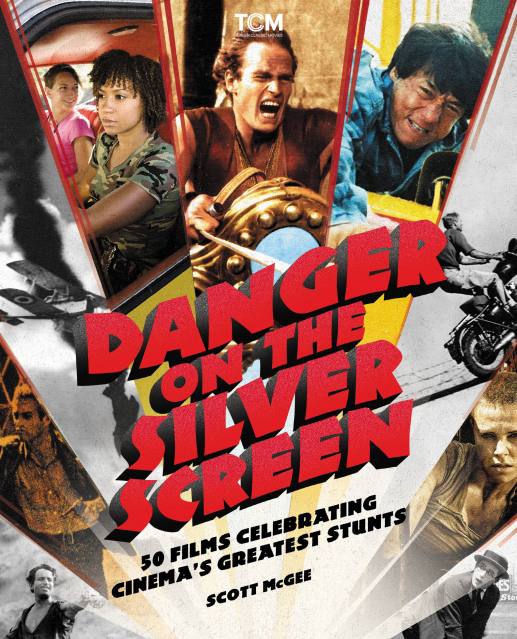

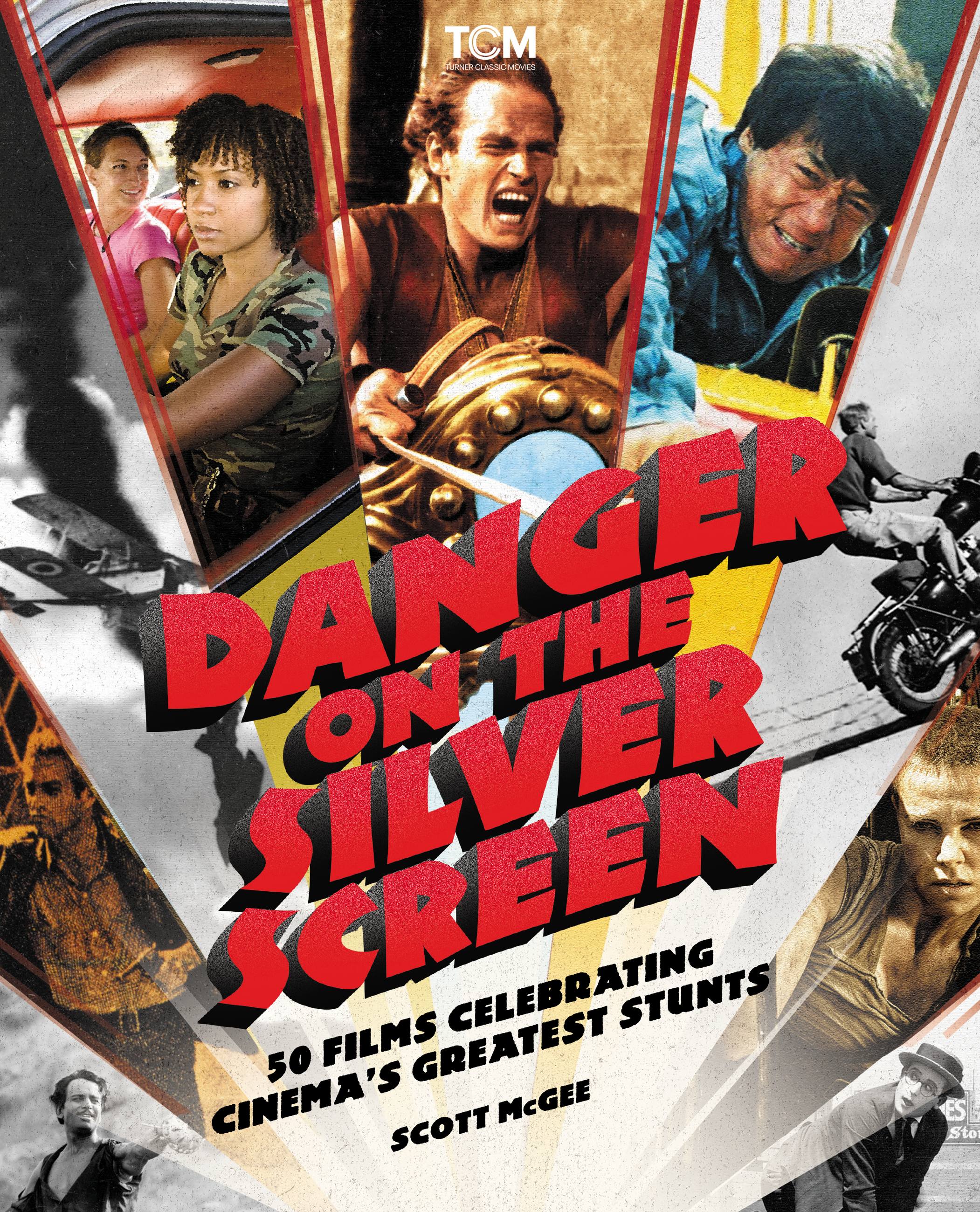

Danger on the Silver Screen

50 Films Celebrating Cinema's Greatest Stunts

Contributors

By Scott McGee

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Apr 5, 2022

- Page Count

- 288 pages

- Publisher

- Running Press

- ISBN-13

- 9780762474844

Price

$25.99Price

$32.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $25.99 $32.99 CAD

- ebook $13.99 $17.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 5, 2022. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Buckle in and join TCM on a action-packed journey through the history of cinema stunt work in Danger on the Silver Screen. This action-packed guide profiles 50 foundational films with insightful commentary on the history, importance, and evolution of an often overlooked element of film: stunt work. With insightful commentary and additional recommendations to expand your repertoire based on your favorites, Danger on the Silver Screen is a one-of-a-kind guide, perfect for film lovers to learn more about or just brush up on their knowledge of stunt work and includes films such as Ben-Hur (1925 & 1959), The Great K&A Train Robbery (1926), Steamboat Bill Jr. (1928), The Thing from Another World (1951), Bullitt (1968), Live and Let Die (1973), The Blues Brothers (1980), Romancing the Stone (1984), The Matrix (1999), The Bourne Supremacy (2004), John Wick (2014), Mission: Impossible—Rogue Nation (2015), Atomic Blonde (2017), and many more.