By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

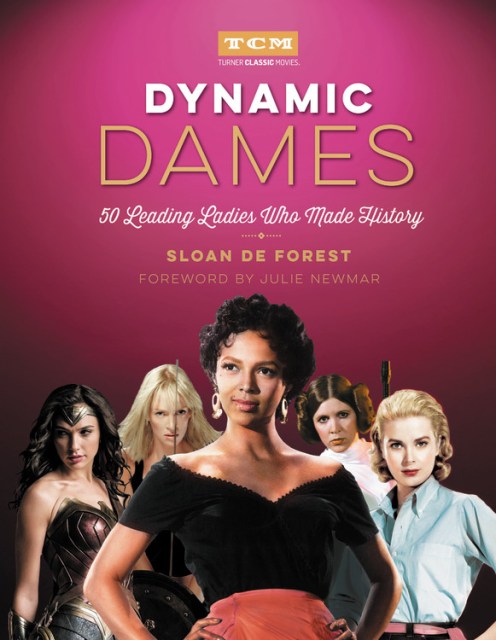

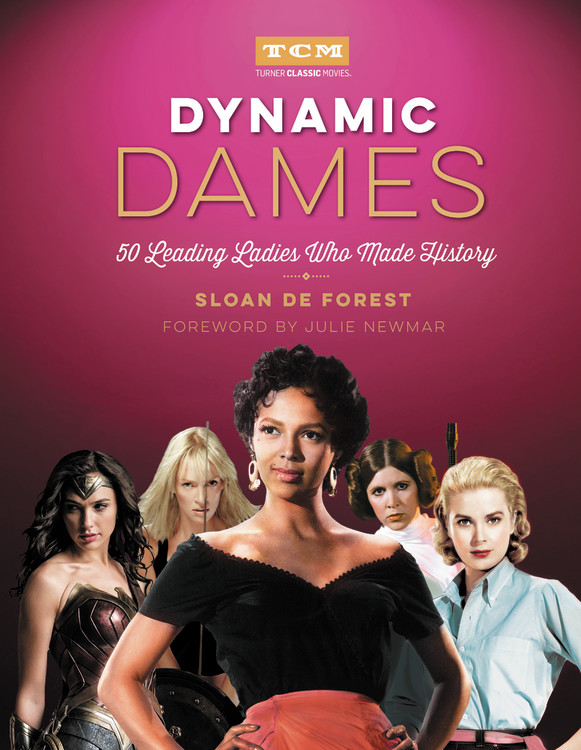

Dynamic Dames

50 Leading Ladies Who Made History

Contributors

Foreword by Julie Newmar

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Jul 2, 2019

- Page Count

- 248 pages

- Publisher

- Running Press

- ISBN-13

- 9780762465521

Price

$23.00Price

$30.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $23.00 $30.00 CAD

- ebook $12.99 $16.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around July 2, 2019. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Celebrate 50 of the most empowering and unforgettable female characters ever to grace the screen, as well as the artists who brought them to vibrant life!

From Scarlett O’Hara to Thelma and Louise to Wonder Woman, strong women have not only lit up the screen, they’ve inspired and fired our imaginations. Some dynamic women are naughty and some are nice, but all of them buck the narrow confines of their expected gender role — whether by taking small steps or revolutionary strides.

Through engaging profiles and more than 100 photographs, Dynamic Dames looks at fifty of the most inspiring female roles in film from the 1920s to today. The characters are discussed along with the exciting off-screen personalities and achievements of the actresses and, on occasion, female writers and directors, who brought them to life.

Among the stars profiled in their most revolutionary roles are Bette Davis, Mae West, Barbara Stanwyck, Josephine Baker, Greta Garbo, Audrey Hepburn, Natalie Wood, Barbra Streisand, Julia Roberts, Meryl Streep, Joan Crawford, Vivien Leigh, Elizabeth Taylor, Dorothy Dandridge, Katharine Hepburn, Pam Grier, Jane Fonda, Gal Gadot, Emma Watson, Zhang Ziyi, Uma Thurman, Jennifer Lawrence, and many more.

From Scarlett O’Hara to Thelma and Louise to Wonder Woman, strong women have not only lit up the screen, they’ve inspired and fired our imaginations. Some dynamic women are naughty and some are nice, but all of them buck the narrow confines of their expected gender role — whether by taking small steps or revolutionary strides.

Through engaging profiles and more than 100 photographs, Dynamic Dames looks at fifty of the most inspiring female roles in film from the 1920s to today. The characters are discussed along with the exciting off-screen personalities and achievements of the actresses and, on occasion, female writers and directors, who brought them to life.

Among the stars profiled in their most revolutionary roles are Bette Davis, Mae West, Barbara Stanwyck, Josephine Baker, Greta Garbo, Audrey Hepburn, Natalie Wood, Barbra Streisand, Julia Roberts, Meryl Streep, Joan Crawford, Vivien Leigh, Elizabeth Taylor, Dorothy Dandridge, Katharine Hepburn, Pam Grier, Jane Fonda, Gal Gadot, Emma Watson, Zhang Ziyi, Uma Thurman, Jennifer Lawrence, and many more.

Series:

-

"Sometimes a book comes into your life that you didn't know you needed until you start reading. And when you do things start to fall into place. That's Dynamic Dames for me. Film historian and author Sloan De Forest delivers with this captivating feminist manifesto.... The writing is engaging and the narrative voice is whip smart and clever."-Raquel Stecher, Out of the Past Blog

-

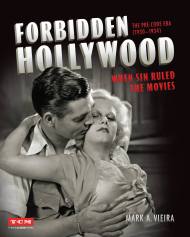

"This gift-worthy volume selects famous leading ladies from the 1920s "pre-code" films, where rebellious behaviors were on display from Clara Bow and Josephine Baker, until the present day... The result is a very satisfying and notably diverse group of talented professionals that have created some of the most memorable moments in film."- Booklist, starred review

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use