Promotion

Shop now and save 20% on your back-to-school purchases & get free shipping on orders $45+ Use code: SCHOOL24

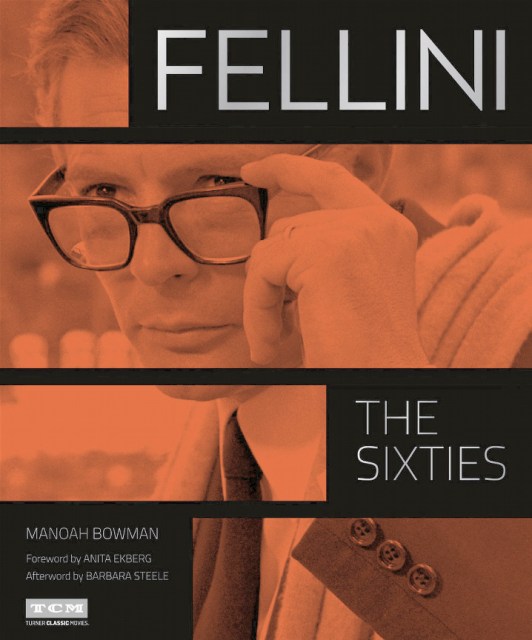

Fellini: The Sixties

Contributors

Foreword by Anita Ekberg

By Turner Classic Movies

Formats and Prices

Price

$65.00Price

$79.95 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $65.00 $79.95 CAD

- ebook $44.99 $58.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 27, 2015. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

These are just a few of the words often used to describe the films of the single most celebrated director in Italy, and one of the most important directors the world has ever known — Federico Fellini. Fifty years since their initial releases, his films of the 1960s still inspire, shock, and delight. More than just encapsulating the ’60s, these films also helped define the style of the decade. With a staggering twelve Academy Award nominations between his four feature films during this period, Fellini reached the heights of fame, film artistry, and worldwide prominence. Studied, analyzed, and re-released over the years, these films continue to amaze each new generation that discovers them. Their impeccable style makes them timeless. Their images make them unforgettable. Their passion brings them to life. And their singular vision makes them unique in all of cinema.

Fellini: The Sixties is a stunning photographic journey through the director’s most iconic classics: La Dolce Vita, 8 1/2, Juliet of the Spirits, and Fellini Satyricon. Carefully selected imagery from the Independent Visions photographic archive, many published here for the first time, illuminate these films as they have never been seen before, and reveal fascinating details of the director’s working style and ebullient personality. With more than 150 photographs struck from original negatives, these images spring to life from the page with the depth and quality of the films themselves. Complemented with insightful essays from contemporary writers, Fellini: The Sixties is a true testament to the man and his work, a remarkable compendium of the legendary filmmaker’s greatest achievements.

About TCM:

Turner Classic Movies is the definitive resource for the greatest movies of all time. It engages, entertains, and enlightens to show how the entire spectrum of classic movies, movie history, and movie-making touches us all and influences how we think and live today.

Series:

- On Sale

- Oct 27, 2015

- Page Count

- 304 pages

- Publisher

- Running Press

- ISBN-13

- 9780762458387

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use