Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

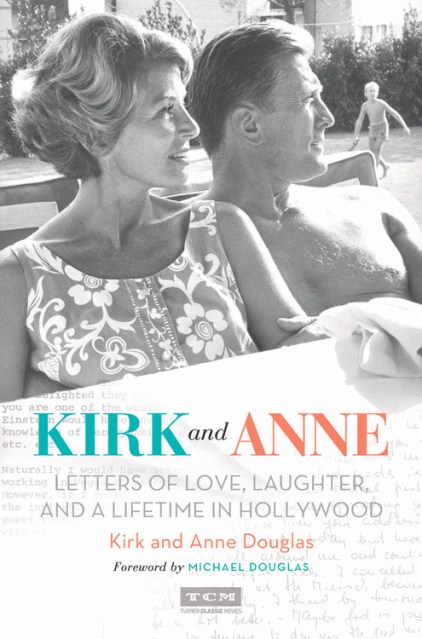

Kirk and Anne

Letters of Love, Laughter, and a Lifetime in Hollywood

Contributors

By Kirk Douglas

By Anne Douglas

Foreword by Michael Douglas

With Marcia Newberger

By Turner Classic Movies

Formats and Prices

Price

$25.00Price

$32.50 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $25.00 $32.50 CAD

- ebook $13.99 $17.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 2, 2017. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

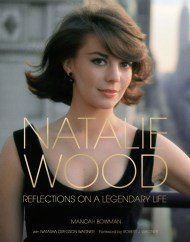

Compiled from Anne’s private archive of letters and photographs, this is an intimate glimpse into the Douglases’ courtship and marriage set against the backdrop of Kirk’s screen triumphs, including The Vikings, Lust For Life, Paths of Glory, and Spartacus. The letters themselves, as well as Kirk and Anne’s vivid descriptions of their experiences, reveal remarkable insight and anecdotes about the legendary figures they knew so well, including Lauren Bacall, Frank Sinatra, Burt Lancaster, Elizabeth Taylor, John Wayne, the Kennedys, and the Reagans. Filled with photos from film sets, private moments, and public events, Kirk and Anne details the adventurous, oftentimes comic, and poignant reality behind the glamour of a Hollywood marriage.

Genre:

- On Sale

- May 2, 2017

- Page Count

- 240 pages

- Publisher

- Running Press

- ISBN-13

- 9780762462179

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use