Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

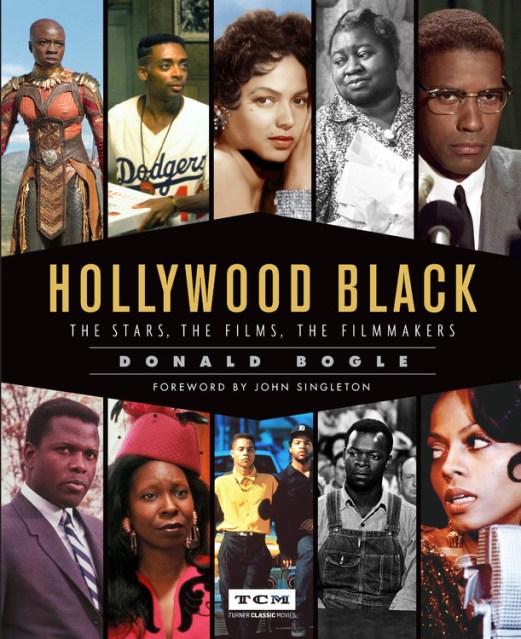

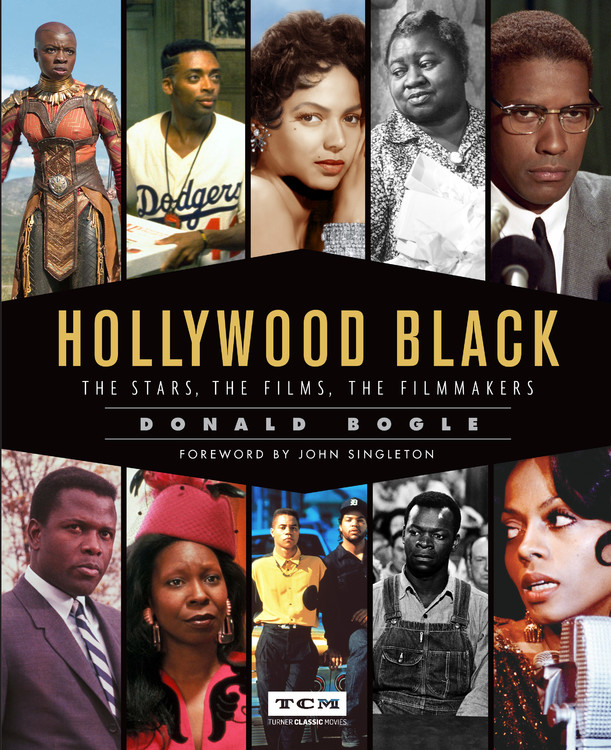

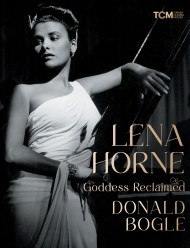

Hollywood Black

The Stars, the Films, the Filmmakers

Contributors

By Donald Bogle

Foreword by John Singleton

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- May 7, 2019

- Page Count

- 264 pages

- Publisher

- Running Press

- ISBN-13

- 9780762491414

Price

$35.00Price

$44.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $35.00 $44.00 CAD

- ebook $16.99 $21.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $27.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 7, 2019. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Filled with photographs and stories of stars and filmmakers on set and off, Hollywood Black tells an enthralling, underappreciated history as it’s never before been told. Explore the rise of independent African American filmmakers and the changes in the film industry with the arrival of sound motion pictures and the Great Depression. More often than not, Black performers were saddled with rigidly stereotyped roles, but some gifted performers, most notably Hattie McDaniel in Gone With the Wind (1939), were able to turn in significant performances.

Dive deep into how Dorothy Dandridge became the first African American to earn a Best Actress Oscar nomination for Carmen Jones (1954) and how Sidney Poitier broke ground in the industry. Follow the emergence of stars such as Morgan Freeman, Halle Berry, Denzel Washington, Viola Davis, Cicely Tyson, Richard Pryor, Angela Bassett, Eddie Murphy, and Whoopi Goldberg, and of directors Spike Lee and John Singleton. The history comes into the new millennium with filmmakers Barry Jenkins (Moonlight), Ava Du Vernay (Selma),and Ryan Coogler (Black Panther) in this enthralling compendium of film.

Series:

-

"This book engagingly chronicles the challenges and achievements of African Americans in Hollywood....Bogle's narrative style makes for absorbing reading, and the book's glossy, photo-filled pages will further attract readers."Booklist

-

"Utterly essential and sophisticated..."-Jeff Simon, Buffalo News

-

"The leading scholar and historian on African Americans in film puts it all in one volume in this well-illustrated study."Milwaukee Journal Sentinel

-

"A superb and detailed book that both educates and informs. I can't recommend this title enough."DVDCorner.net

-

"No one knows more (or has written more extensively) about the history of African-Americans' contributions to cinema than Donald Bogle."-Leonard Maltin, LeonardMaltin.com

-

"Little-known stories, megawatt stars on-set and off, and a sweeping history of Black film—from silent films to the millennium and beyond—make this triumphant tome a must-read for any movie lover.”-Lindsay Powers, Amazon Book Review Editor