By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

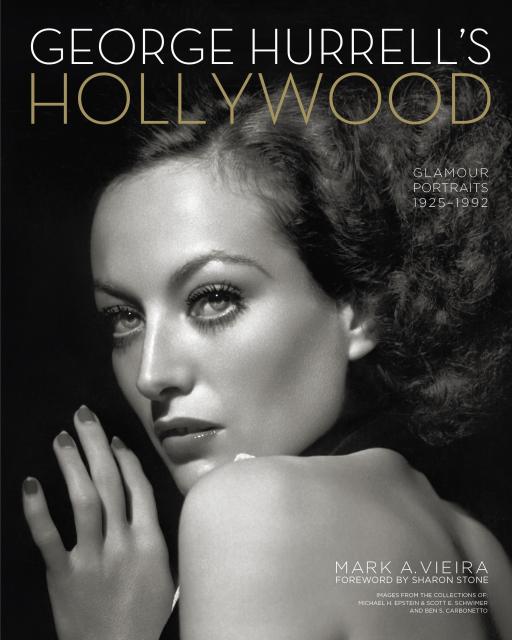

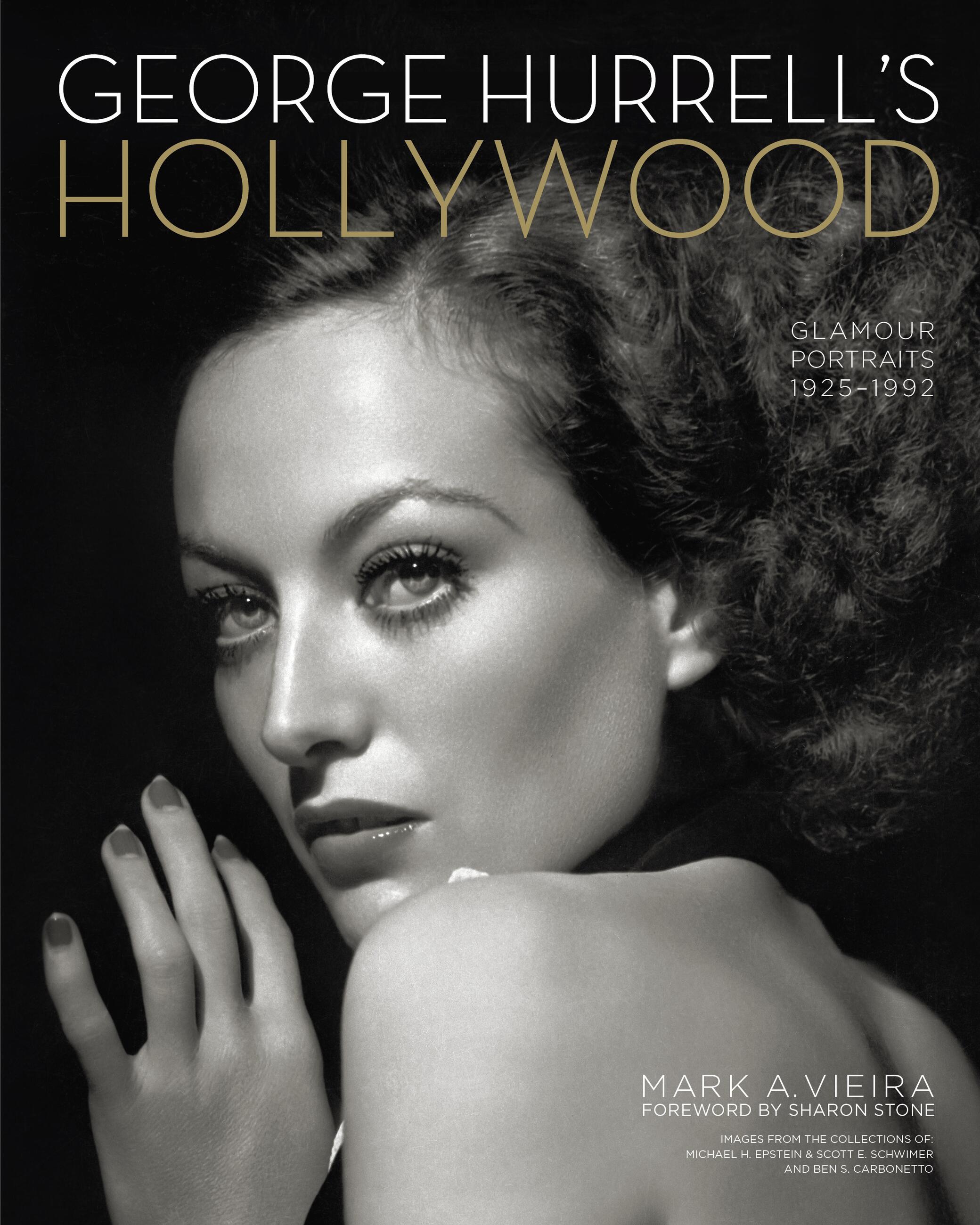

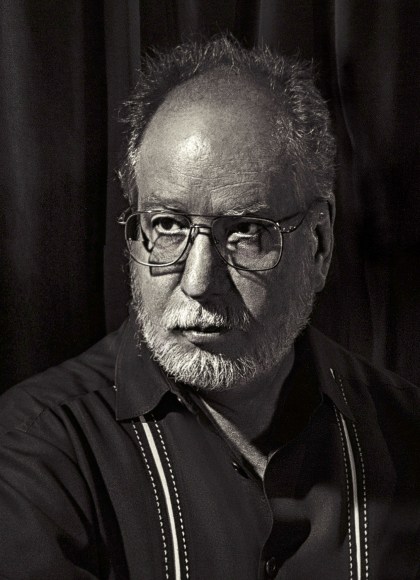

George Hurrell’s Hollywood

Glamour Portraits, 1925-1992

Contributors

Foreword by Sharon Stone

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Sep 19, 2023

- Page Count

- 416 pages

- Publisher

- Running Press

- ISBN-13

- 9780762484607

Price

$34.99Price

$43.99 CADFormat

Format:

Trade Paperback (Revised) $34.99 $43.99 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 19, 2023. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

George Hurrell was called the “Rembrandt of Hollywood.” Before his arrival, movie star portraits were “soft focus” and undistinguished, derivative of the Main Street USA portrait salon. Hurrell instituted a sharp, dramatic look. The vibrant, temperamental artist was an original, loved by the subjects he glamorized. For these performers, a Hurrell portrait was the passport to immortality.

In this paperback edition of photographer and historian Mark A. Vieira’s original volume, the author offers a wealth of new images to illustrate a compelling narrative. Featuring rare and never-before-published portraits and behind-the-scenes shots, George Hurrell’s Hollywood covers Hurrell’s entire career, from his beginnings as a Los Angeles society photographer to his finale as the celebrity photographer who became a celebrity himself. More than 400 pristine images showcase his work with Hollywood icons from 1929 to 1992. Vieira’s text recounts the artist’s life, from his childhood to the heyday of his career as a starmaker, through untold stories of his fall from grace and eventual comeback.

Filled with previously unseen photos of the biggest stars across more than six decades and abounding with fresh insight, this volume is not only the ultimate showcase of the trailblazing artist’s work but an indispensable treasury of Hollywood lore.

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use