By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

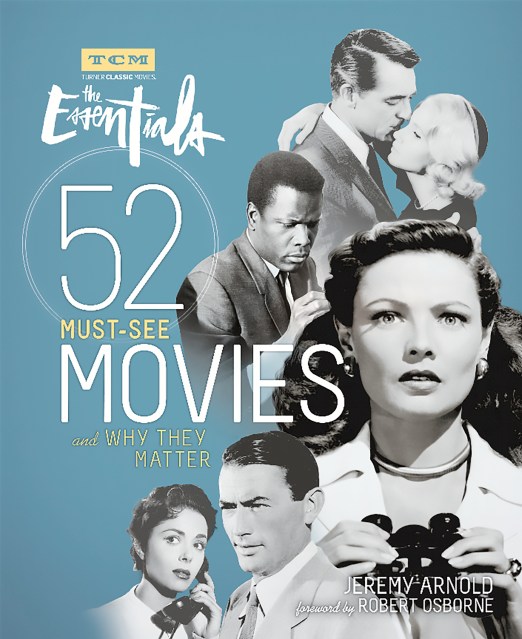

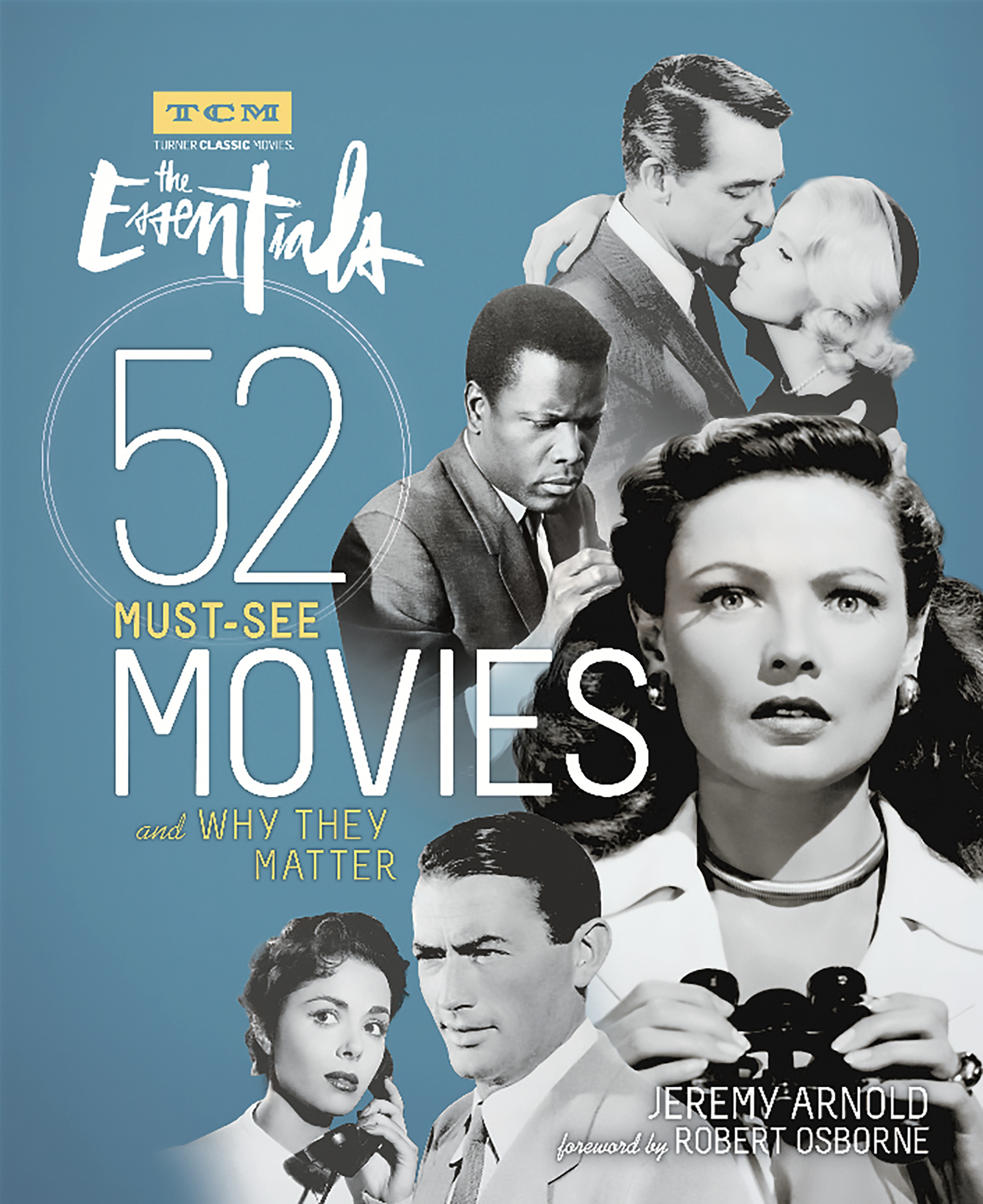

The Essentials

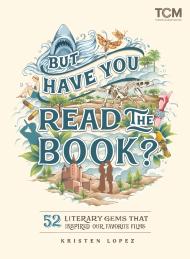

52 Must-See Movies and Why They Matter

Contributors

Foreword by Robert Osborne

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- May 3, 2016

- Page Count

- 288 pages

- Publisher

- Running Press

- ISBN-13

- 9780762459469

Price

$25.99Price

$35.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $25.99 $35.99 CAD

- ebook $16.99 $20.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 3, 2016. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

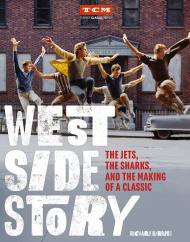

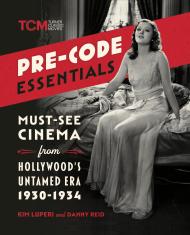

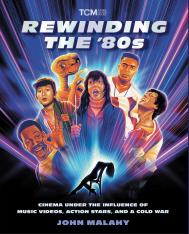

Based on the TCM series, The Essentials book showcases fifty-two must-see movies from the silent era through the early 1980s. Readers can enjoy one film per week, for a year of stellar viewing, or indulge in their own classic movie festival. Each film is profiled with insightful notes on why it’s an Essential, a guide to must-see moments, and running commentary from TCM’s Robert Osborne and Essentials guest hosts past and present, including Sally Field, Drew Barrymore, Alec Baldwin, Rose McGowan, Carrie Fisher, Molly Haskell, Peter Bogdanovich, Sydney Pollack, and Rob Reiner. Some long-championed classics appear within these pages; other selections may surprise you.

Featuring full-color and black-and-white photography of the greatest stars in movie history, The Essentials is your curated guide to fifty-two films that define the meaning of the word “classic.”

Series:

-

"[An] excellent book. Author Arnold distills why each movie is a must-see, and augments his knowledgeable text with sidebar quotes from various TCM hosts... Handsomely designed and packed with great photos, The Essentials would be a perfect gift for a young person who's just dipping his or her toe into these waters…but I found it equally appealing."

—Leonard Maltin, leonardmaltin.com

"An entertaining read... Beautifully-designed and illustrated... Author Jeremy Arnold does a superb job presenting the reasons why a particular film matters."

—Raymond Benson, Cinema Retro

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use