Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

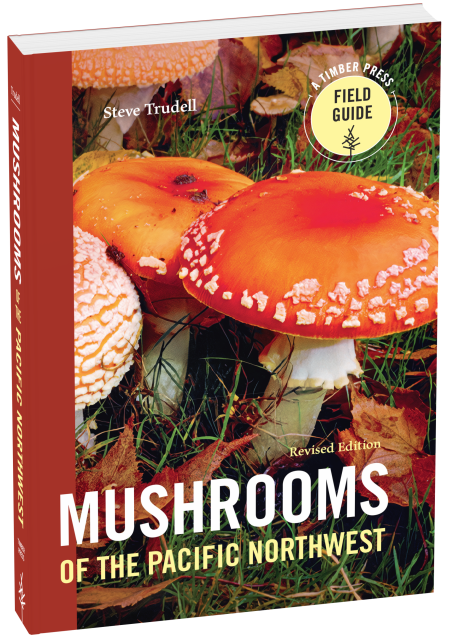

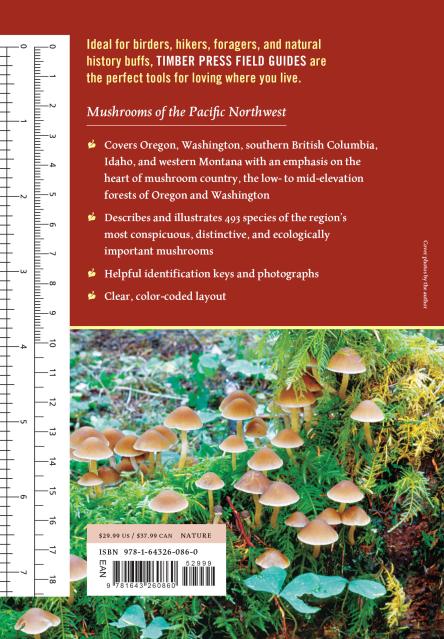

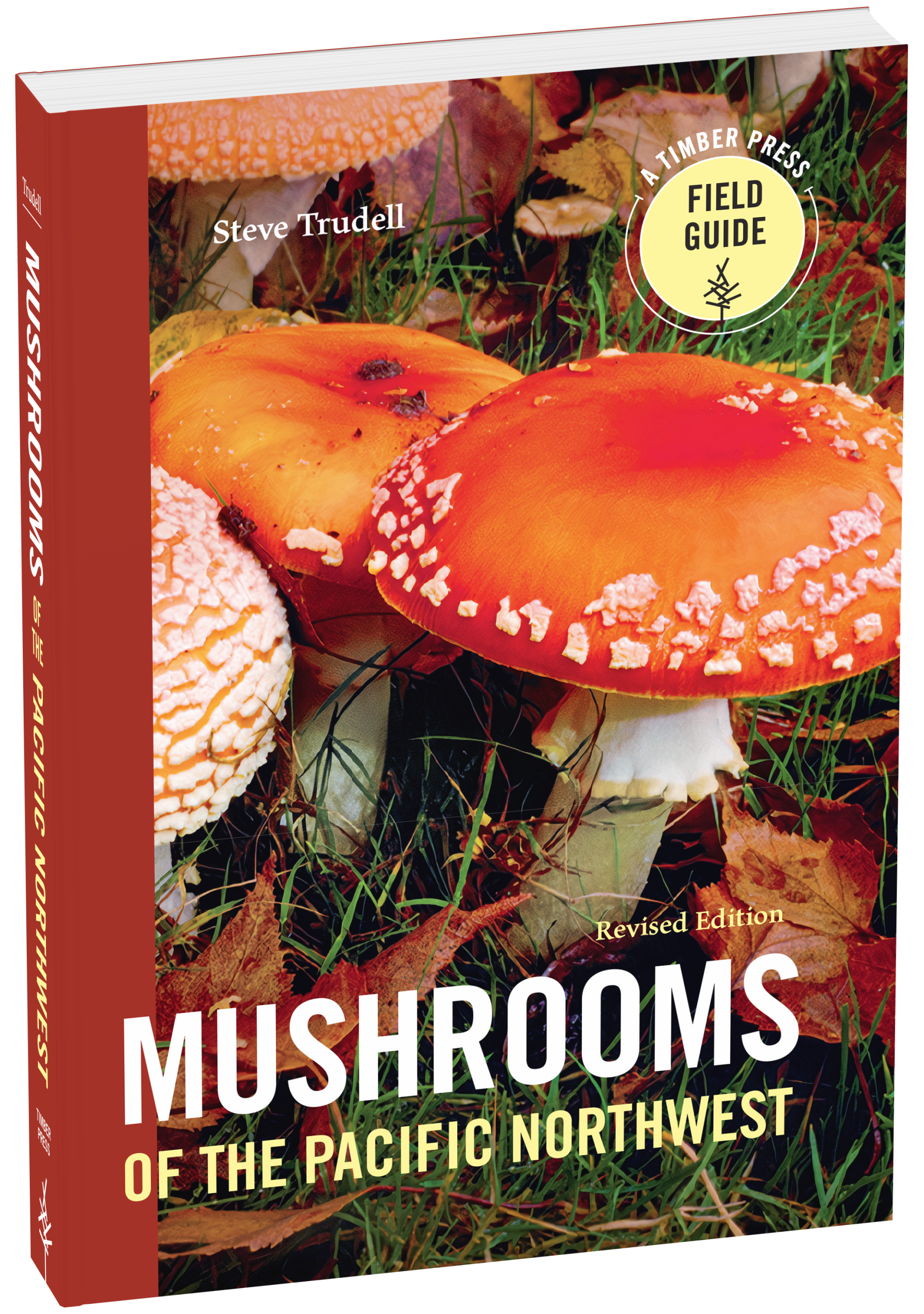

Mushrooms of the Pacific Northwest, Revised Edition

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$29.99Price

$37.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $29.99 $37.99 CAD

- ebook (Revised) $14.99 $19.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 25, 2022. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

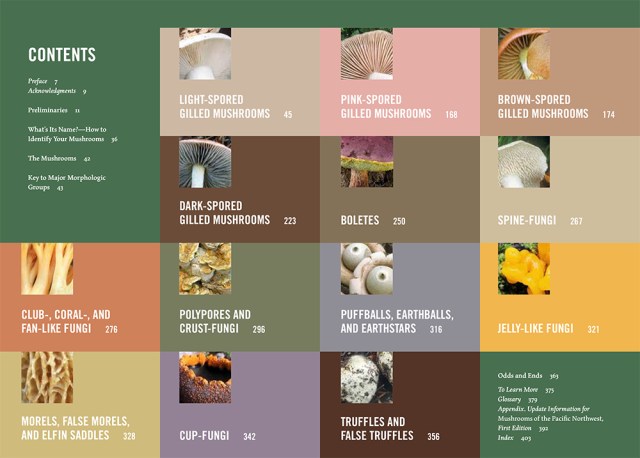

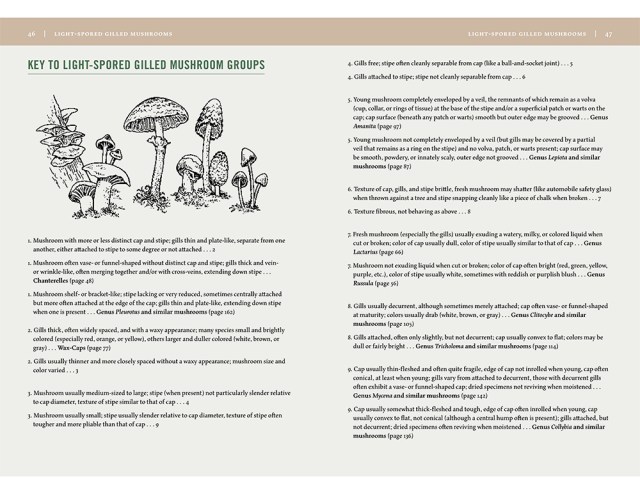

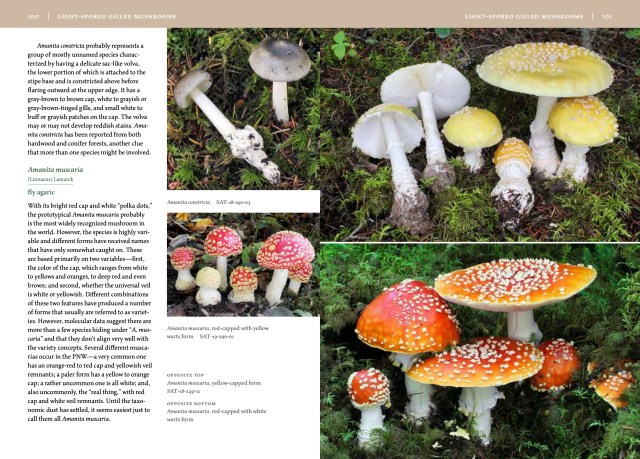

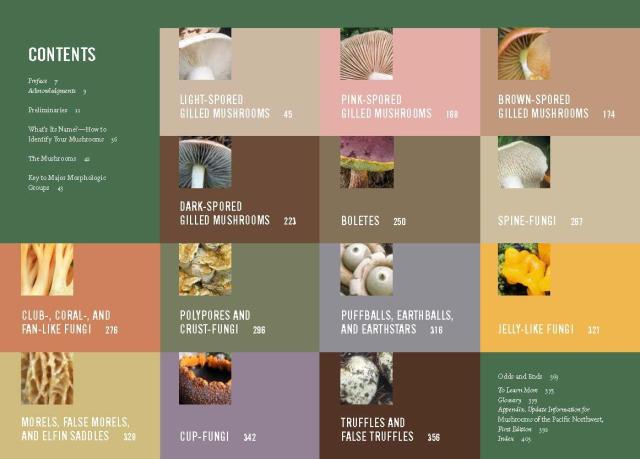

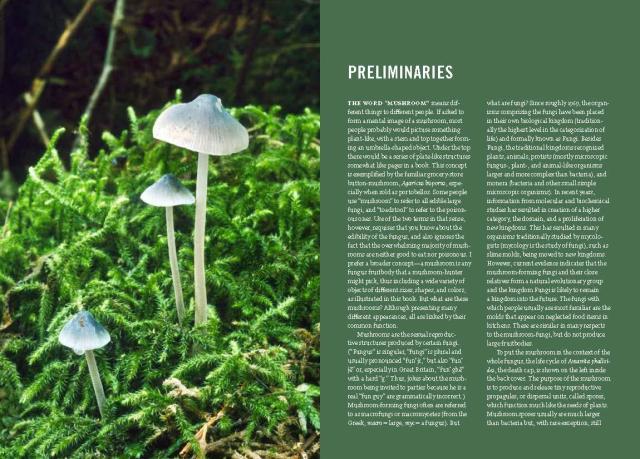

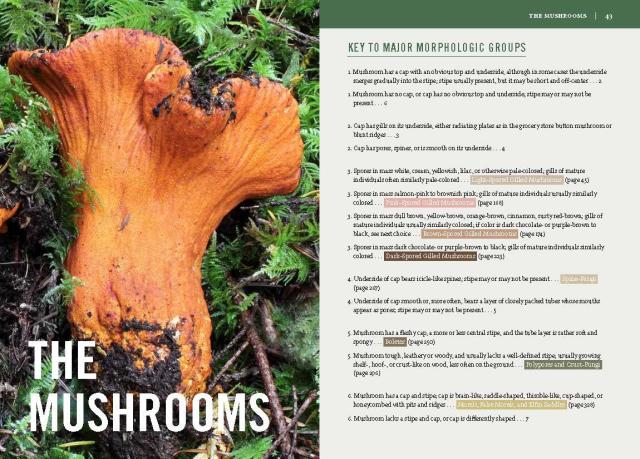

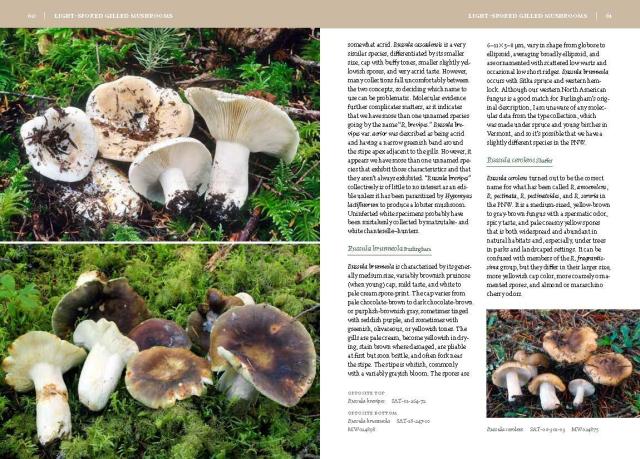

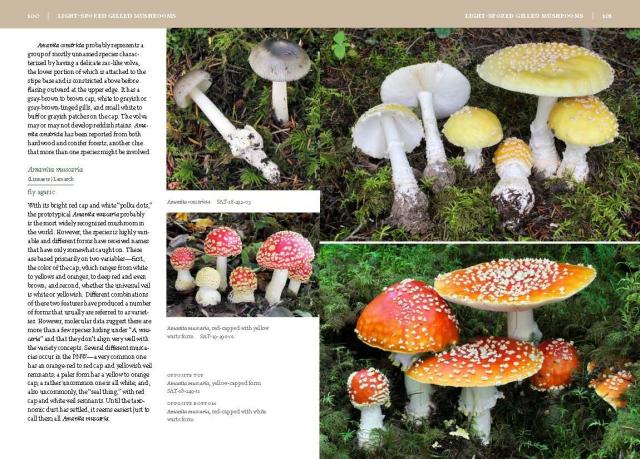

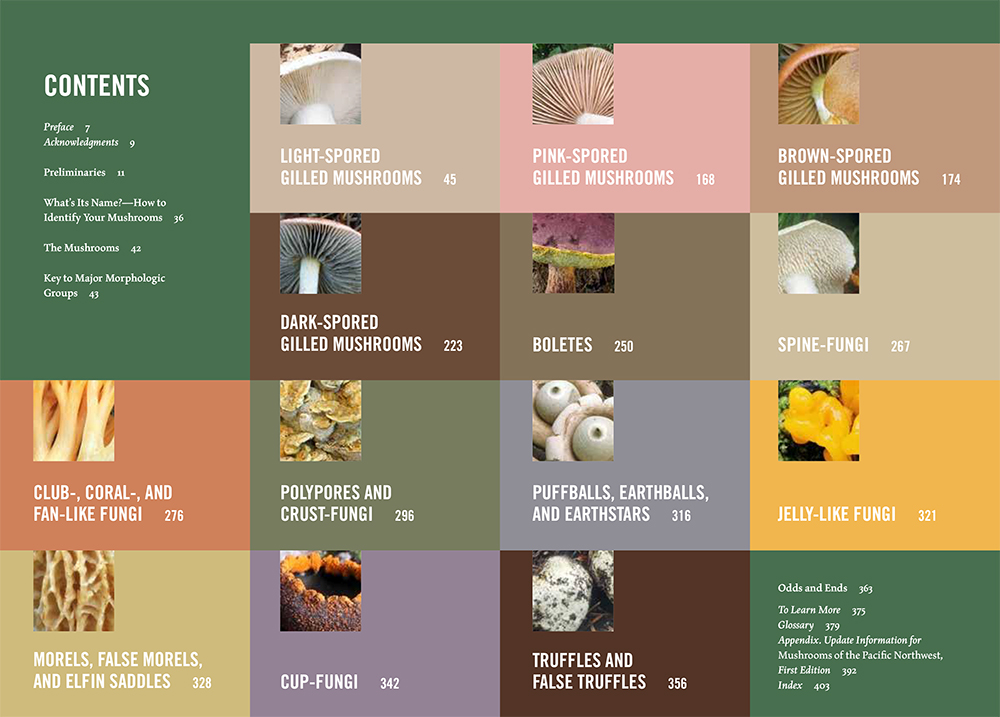

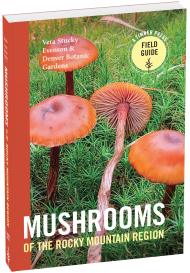

Mushrooms of the Pacific Northwest is a comprehensive field guide to the most conspicuous, distinctive, and ecologically important mushrooms found in the region. With helpful identification keys and photographs and a clear, color-coded layout, Mushrooms of the Pacific Northwest is ideal for hikers, foragers, and natural history buffs and is the perfect tool for loving where you live.

- Covers Oregon, Washington, and British Columbia

- Describes and illustrates 493 species

- 530 photographs, with additional keys and diagrams

- Clear color-coded layout

Genre:

-

“This one goes out into the field with me when I'm foraging.”Discover Our Coast

- On Sale

- Oct 25, 2022

- Page Count

- 416 pages

- Publisher

- Timber Press

- ISBN-13

- 9781643260860

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use