Promotion

Sign up for our newsletters to receive 20% off! Shop now. Exclusions apply.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

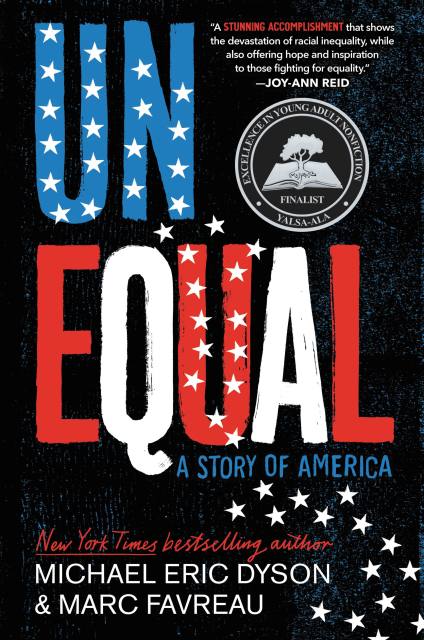

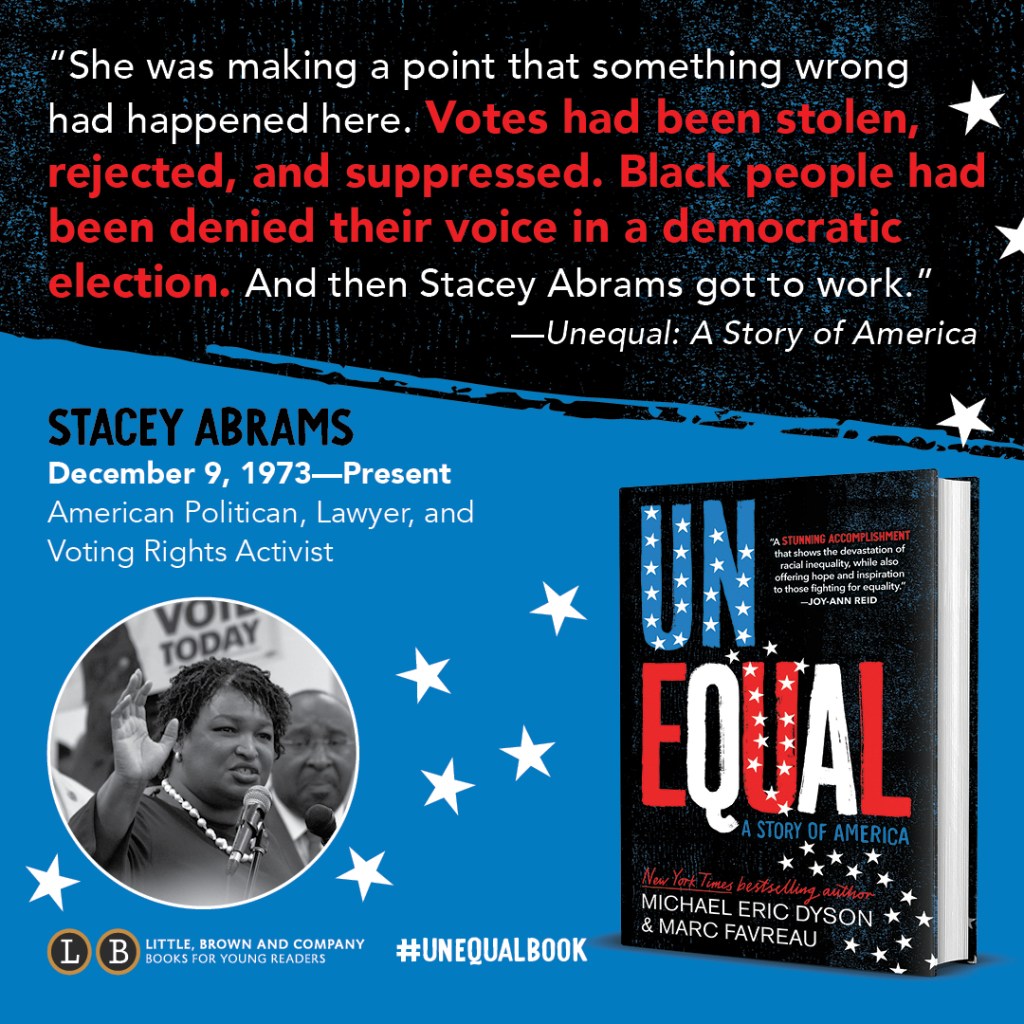

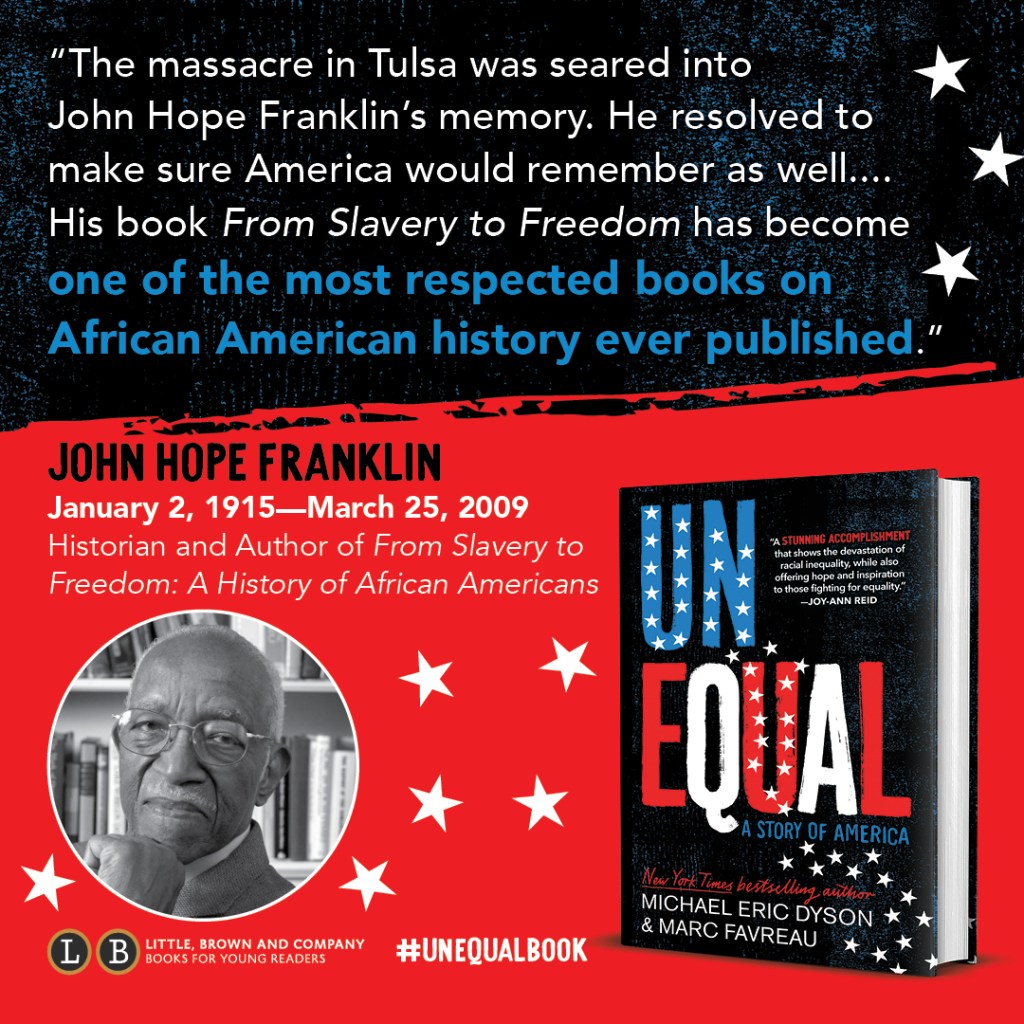

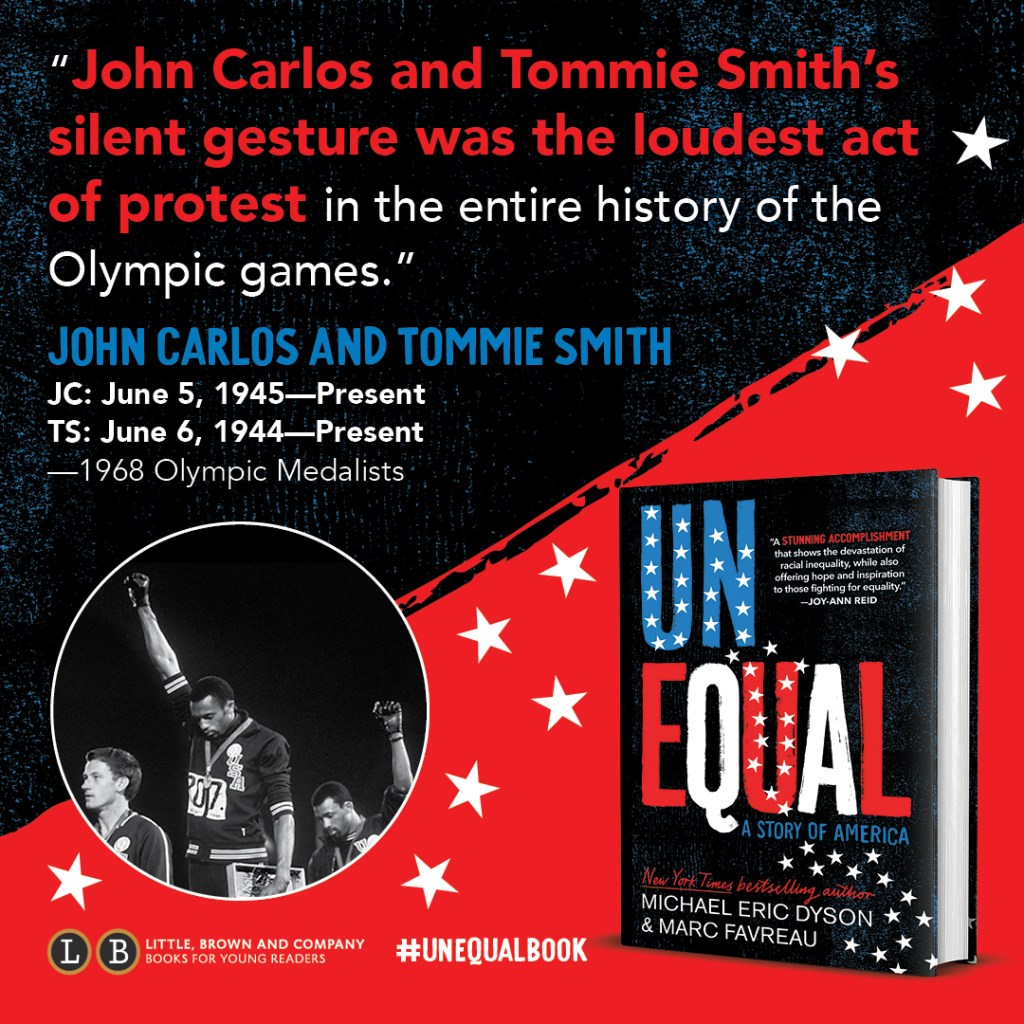

Unequal

A Story of America

Contributors

By Marc Favreau

Formats and Prices

Price

$18.99Price

$23.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $18.99 $23.99 CAD

- ebook $9.99 $12.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $24.99

- Trade Paperback $12.99 $16.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 3, 2022. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Finalist for the YALSA Excellence in Nonfiction for Young Adults Award

New York Times bestselling author Michael Eric Dyson and critically acclaimed author Marc Favreau show how racial inequality permeates every facet of American society, through the lens of those pushing for meaningful change

The true story of racial inequality—and resistance to it—is the prologue to our present. You can see it in where we live, where we go to school, where we work, in our laws, and in our leadership. Unequal presents a gripping account of the struggles that shaped America and the insidiousness of racism, and demonstrates how inequality persists. As readers meet some of the many African American people who dared to fight for a more equal future, they will also discover a framework for addressing racial injustice in their own lives.

-

A YALSA-ALA Excellence in Nonfiction for Young Adult Award Finalist

A School Library Journal Best Book of the Year

A New York Public Library Best Book of 2022

A Cooperative Children’s Book Center Children’s Choices list pick

A Bank Street Best Book of the Year

A Children's Book Council Teacher Favorite -

Common, Grammy Award-winning artist, author, actor, and activist

"Michael Eric Dyson is one the greatest intellectuals and thought provokers of our time. In this book he and Marc Favreau realize we are the fruit of generations of giants who labored for and demanded a more equal America. Read Unequal to learn their stories—and our own."

-

Robin DiAngelo, #1 bestselling author of White Fragility: Why It’s So Hard for White People to Talk About Racism

"With clarity and insight, Unequal illuminates how racial inequality is built into every aspect of American society. In gripping prose, Michael Eric Dyson and Marc Favreau draw clear lines between past and present struggles for racial equality to reveal what is required of us if we truly want to live in a society without racism."

-

Joy-Ann Reid, bestselling author and host of The ReidOut on MSNBC

"Michael Eric Dyson has long offered a vital perspective on race in America. Unequal is a stunning accomplishment, where Dr. Dyson and Marc Favreau transport readers across the country and across time to show the devastation and insidiousness of racial inequality, while also offering hope and inspiration to those fighting for equality."

-

SLJ, starred review

* "Empowering, profound, and necessary, purchase for all collections serving young adults."

-

Publishers Weekly, starred review

* "Crucial…This searing look at attempts to block students 'from learning the truth of inequality in the United States' encourages readers to acknowledge the deep-seated presence of structural racism in America. A must-read and a must-teach."

-

Kirkus Reviews, starred review

* "This accessible, riveting collection will inspire readers to claim responsibility for helping to ensure that the U.S. one day lives up to its most ethical professed ideals. Grounded in evidence and optimistic: uplifts the social power of studying Black American freedom fighters."

-

SLC, starred review

* “This is a necessary resource and will inspire students to promote social justice.”

- On Sale

- May 3, 2022

- Page Count

- 368 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown Books for Young Readers

- ISBN-13

- 9780759557017

Book Club Guide

Praise

-

A YALSA-ALA Excellence in Nonfiction for Young Adult Award Finalist

A School Library Journal Best Book of the Year

A New York Public Library Best Book of 2022

A Cooperative Children’s Book Center Children’s Choices list pick

A Bank Street Best Book of the Year

A Children's Book Council Teacher Favorite -

Common, Grammy Award-winning artist, author, actor, and activist

"Michael Eric Dyson is one the greatest intellectuals and thought provokers of our time. In this book he and Marc Favreau realize we are the fruit of generations of giants who labored for and demanded a more equal America. Read Unequal to learn their stories—and our own."

-

Robin DiAngelo, #1 bestselling author of White Fragility: Why It’s So Hard for White People to Talk About Racism

"With clarity and insight, Unequal illuminates how racial inequality is built into every aspect of American society. In gripping prose, Michael Eric Dyson and Marc Favreau draw clear lines between past and present struggles for racial equality to reveal what is required of us if we truly want to live in a society without racism."

-

Joy-Ann Reid, bestselling author and host of The ReidOut on MSNBC

"Michael Eric Dyson has long offered a vital perspective on race in America. Unequal is a stunning accomplishment, where Dr. Dyson and Marc Favreau transport readers across the country and across time to show the devastation and insidiousness of racial inequality, while also offering hope and inspiration to those fighting for equality."

-

SLJ, starred review

* "Empowering, profound, and necessary, purchase for all collections serving young adults."

-

Publishers Weekly, starred review

* "Crucial…This searing look at attempts to block students 'from learning the truth of inequality in the United States' encourages readers to acknowledge the deep-seated presence of structural racism in America. A must-read and a must-teach."

-

Kirkus Reviews, starred review

* "This accessible, riveting collection will inspire readers to claim responsibility for helping to ensure that the U.S. one day lives up to its most ethical professed ideals. Grounded in evidence and optimistic: uplifts the social power of studying Black American freedom fighters."

-

SLC, starred review

* “This is a necessary resource and will inspire students to promote social justice.”

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use