Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

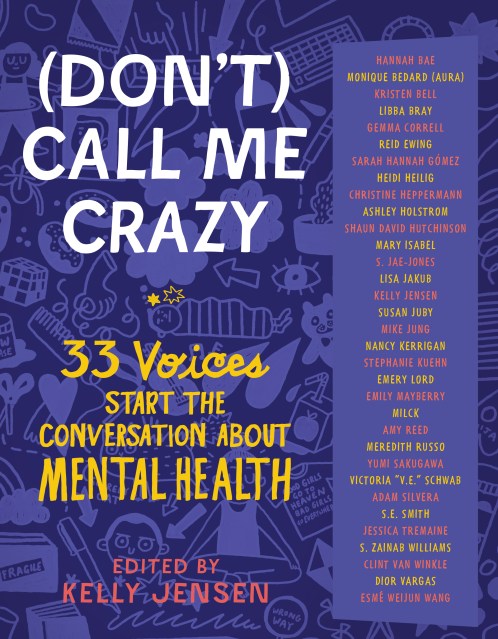

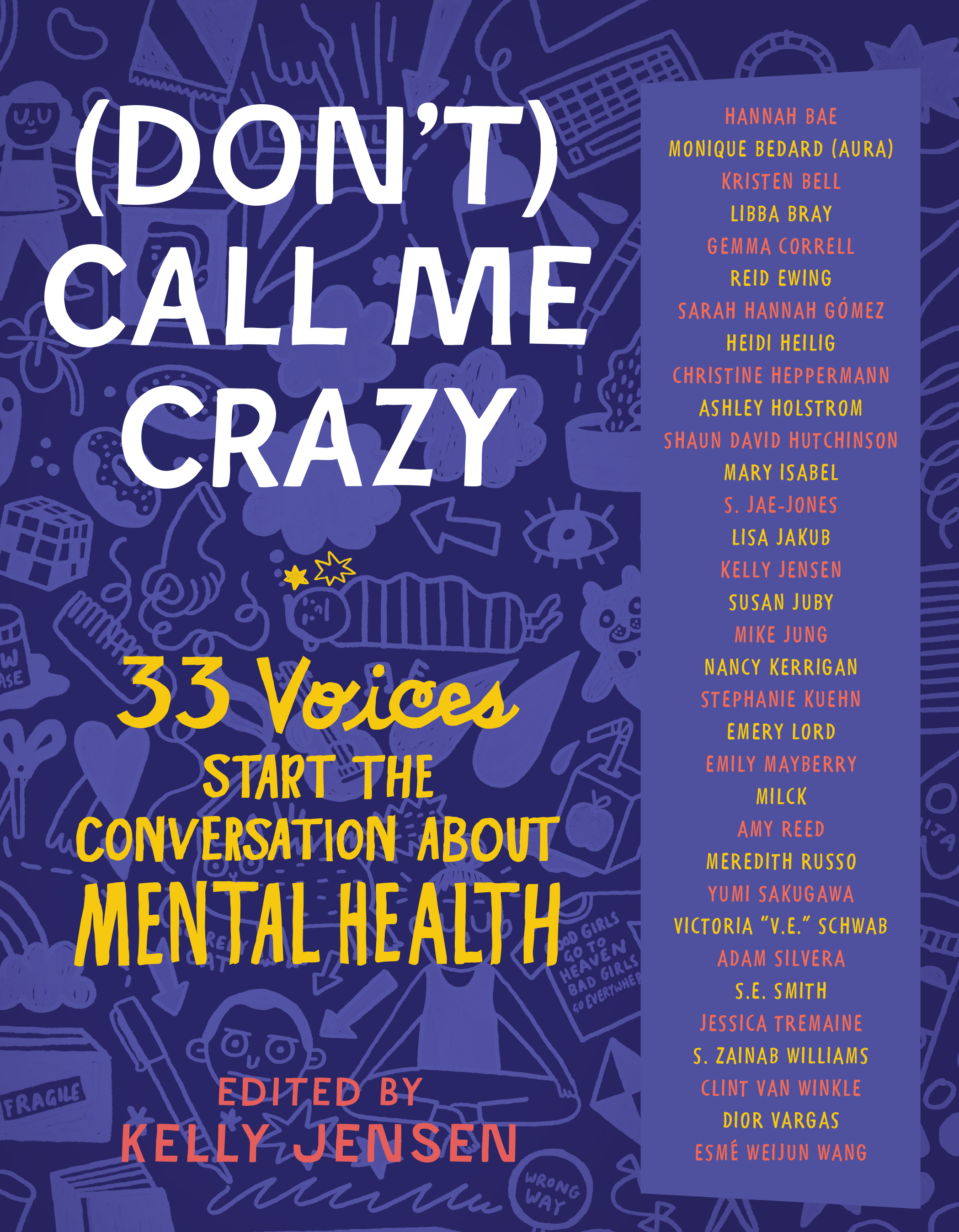

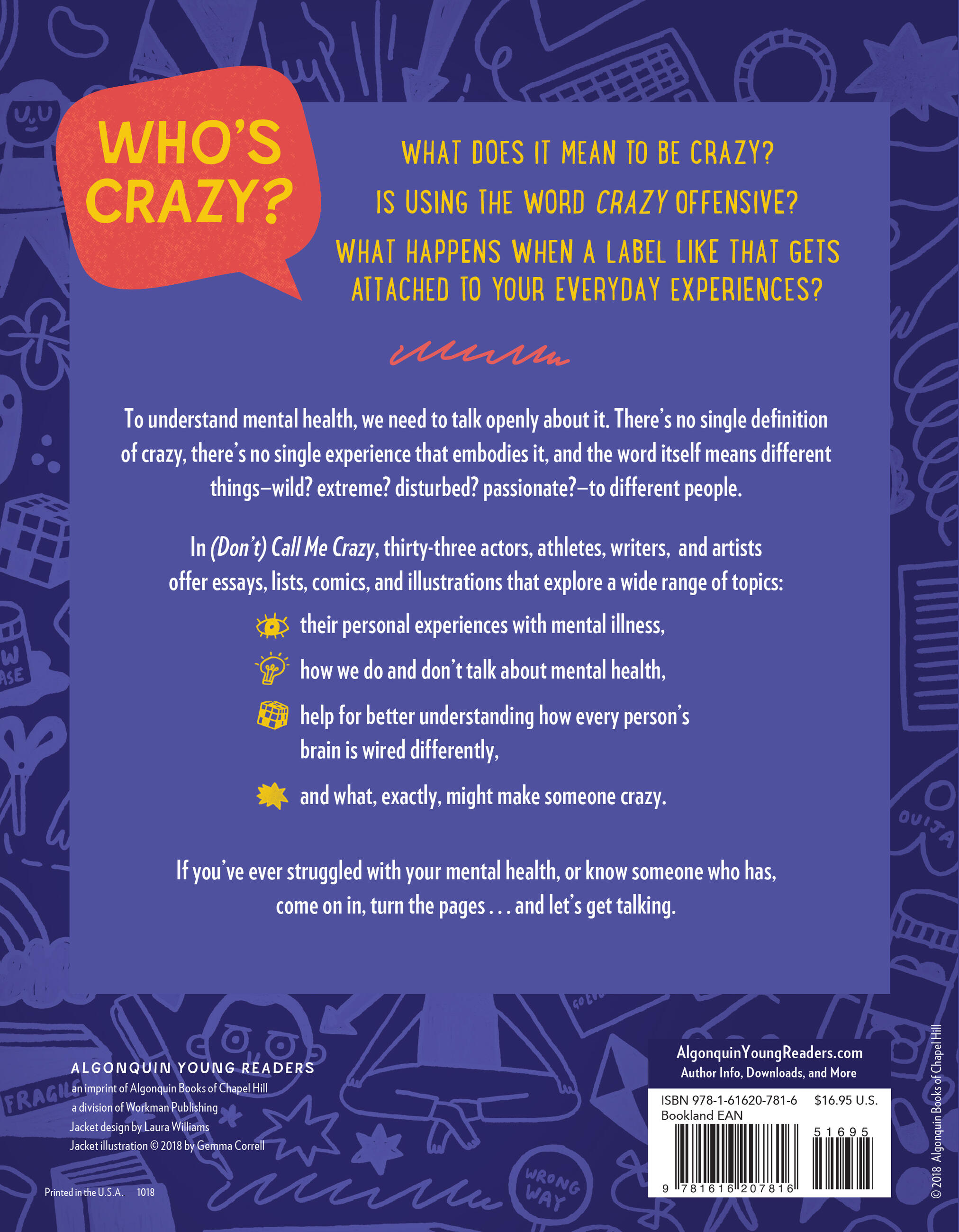

(Don't) Call Me Crazy

33 Voices Start the Conversation about Mental Health

Contributors

By Kelly Jensen

Formats and Prices

Price

$16.95Price

$22.95 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $16.95 $22.95 CAD

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 2, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

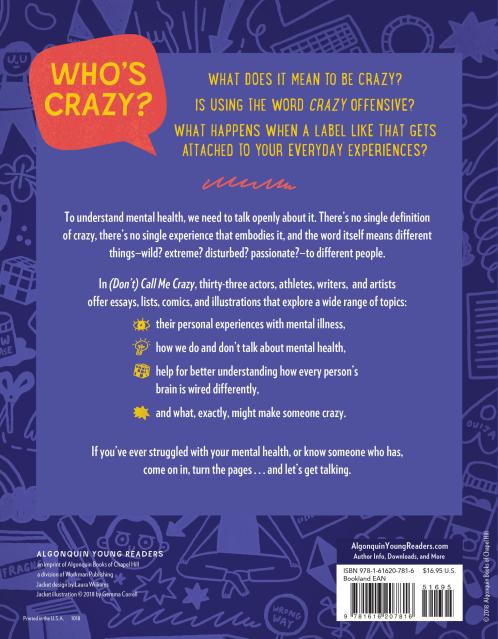

A Washington Post Best Children’s Book of 2018Who’s Crazy?

What does it mean to be crazy? Is using the word crazy offensive? What happens when a label like that gets attached to your everyday experiences?

To understand mental health, we need to talk openly about it. Because there’s no single definition of crazy, there’s no single experience that embodies it, and the word itself means different things—wild? extreme? disturbed? passionate?—to different people.

In (Don’t) Call Me Crazy, thirty-three actors, athletes, writers, and artists offer essays, lists, comics, and illustrations that explore a wide range of topics:

their personal experiences with mental illness,

how we do and don’t talk about mental health,

help for better understanding how every person’s brain is wired differently,

and what, exactly, might make someone crazy.

If you’ve ever struggled with your mental health, or know someone who has, come on in, turn the pages . . . and let’s get talking.

This award-winning anthology is from the highly-praised editor of Here We Are: Feminism for the Real World and Body Talk: 37 Voices Explore Our Radical Anatomy.

.

Genre:

-

A Washington Post Best Children’s Book of 2018

“Jensen has brought together sharp and vivid perspectives concerning mental-health challenges. Featuring writers such as Shaun David Hutchinson, Libba Bray, Adam Silvera and Esmé Weijun Wang, this book asks questions and provides real-life experiences and hope for the future.”

—Washington Post, “Best Children’s Books of 2018”

“This (crucially!) diverse essay collection spans race, gender, sexual orientation, career, and age to hopefully reduce the stigma around mental illness.”

—Bustle

“Empowering . . . deeply resonant . . . With this diverse array of contributors offering a stunning wealth of perspectives on mental health, teens looking for solidarity, comfort, or information will certainly be able to find something that speaks to them. Resources and further reading make this inviting, much-needed resource even richer.”

—Booklist

“Lively, compelling . . . the raw, informal approach to the subject matter will highly appeal to young people who crave understanding and validation . . . This highly readable and vital collection demonstrates the multiplicity of ways that mental health impacts individuals.”

—Kirkus Reviews

“Thought-provoking . . . Misconceptions about mental health still abound, making this honest yet hopeful title a vital selection.”

—School Library Journal, starred review“This is a much-needed collection of writing about mental health and the impact it has . . . with mental health stigma unfortunately still being a serious problem, teens really need books like this right now.”

—Cultured Vultures

“The spectrum of voices and stories is wonderful to read. Not only that, but it mixes already published pieces as well as original memoir type stories. (Don’t) Call Me Crazy deals with the power of diagnosis/labels not being the same for everyone, and the inequality in the mental health discussion. It is an anthology that stresses individual experiences, support, and listening. If you want to read more about it, Jensen also includes a reading list. So it leaves you not only with more experience, but a jumping board of where to go next. It is equally hopeful, cathartic, inspiring and real.”

—Utopia State of Mind

- On Sale

- Oct 2, 2018

- Page Count

- 240 pages

- Publisher

- Algonquin Young Readers

- ISBN-13

- 9781616207816

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use