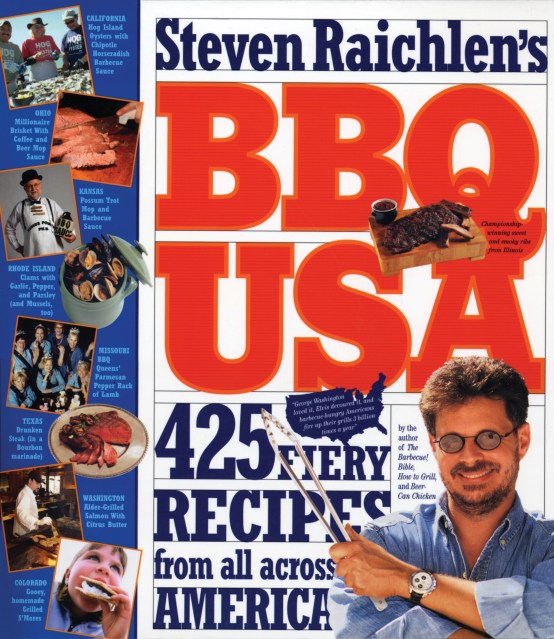

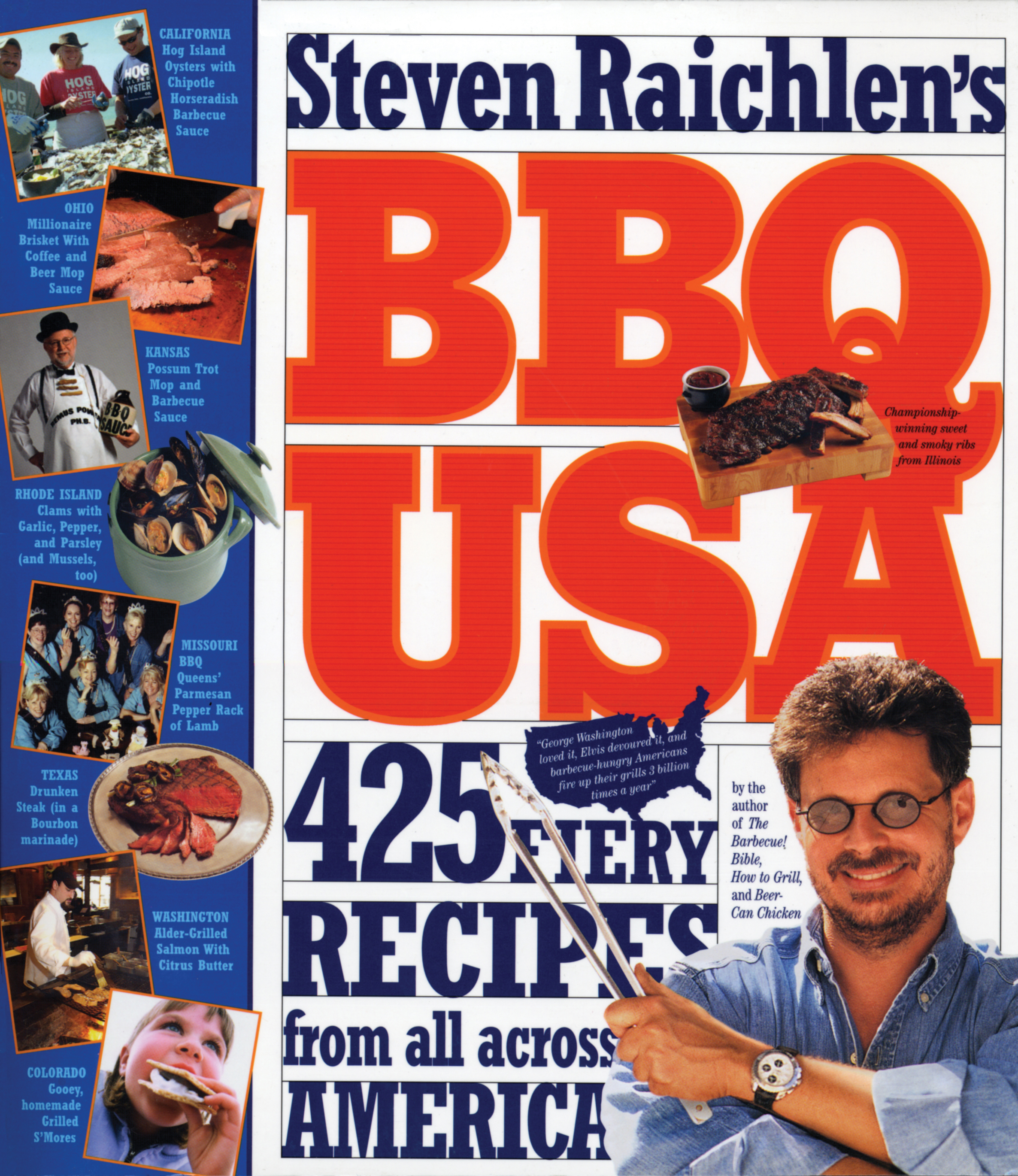

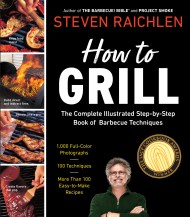

BBQ USA

425 Fiery Recipes from All Across America

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$16.99Price

$21.99 CADFormat

Format:

ebook (Digital original) $16.99 $21.99 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 22, 2003. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

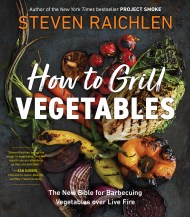

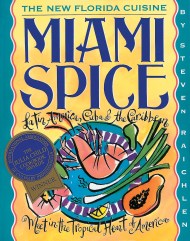

Steven Raichlen, a national barbecue treasure and author of The Barbecue! Bible, How to Grill, and other books in the Barbecue! Bible series, embarks on a quest to find the soul of American barbecue, from barbecue-belt classics-Lone Star Brisket, Lexington Pulled Pork, K.C. Pepper Rub, Tennessee Mop Sauce-to the grilling genius of backyards, tailgate parties, competitions, and local restaurants.In 450 recipes covering every state as well as Canada and Puerto Rico, BBQ USA celebrates the best of regional live-fire cooking. Finger-lickin’ or highfalutin; smoked, rubbed, mopped, or pulled; cooked in minutes or slaved over all through the night, American barbecue is where fire meets obsession. There’s grill-crazy California, where everything gets fired up – dates, Caesar salad, lamb shanks, mussels. Latin-influenced Florida, with its Chimichurri Game Hens and Mojo-Marinated Pork on Sugar Cane. Maple syrup flavors the grilled fare of Vermont; Wisconsin throws its kielbasa over the coals; Georgia barbecues Vidalias; and Hawaii makes its pineapples sing. Accompanying the recipes are hundreds of tips, techniques, sidebars, and pit stops. It’s a coast-to-coast extravaganza, from soup (grilled, chilled, and served in shooters) to nuts (yes, barbecued peanuts, from Kentucky).

Genre:

- On Sale

- Apr 22, 2003

- Page Count

- 784 pages

- Publisher

- Workman Publishing Company

- ISBN-13

- 9780761159582

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use