Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

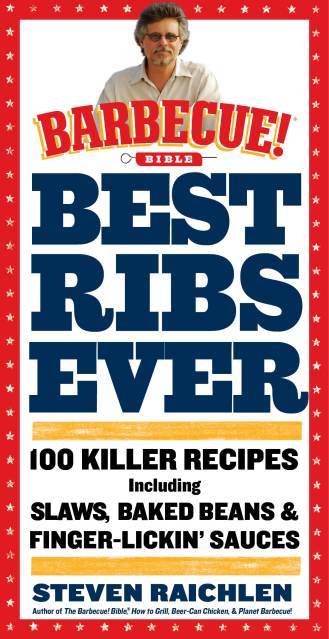

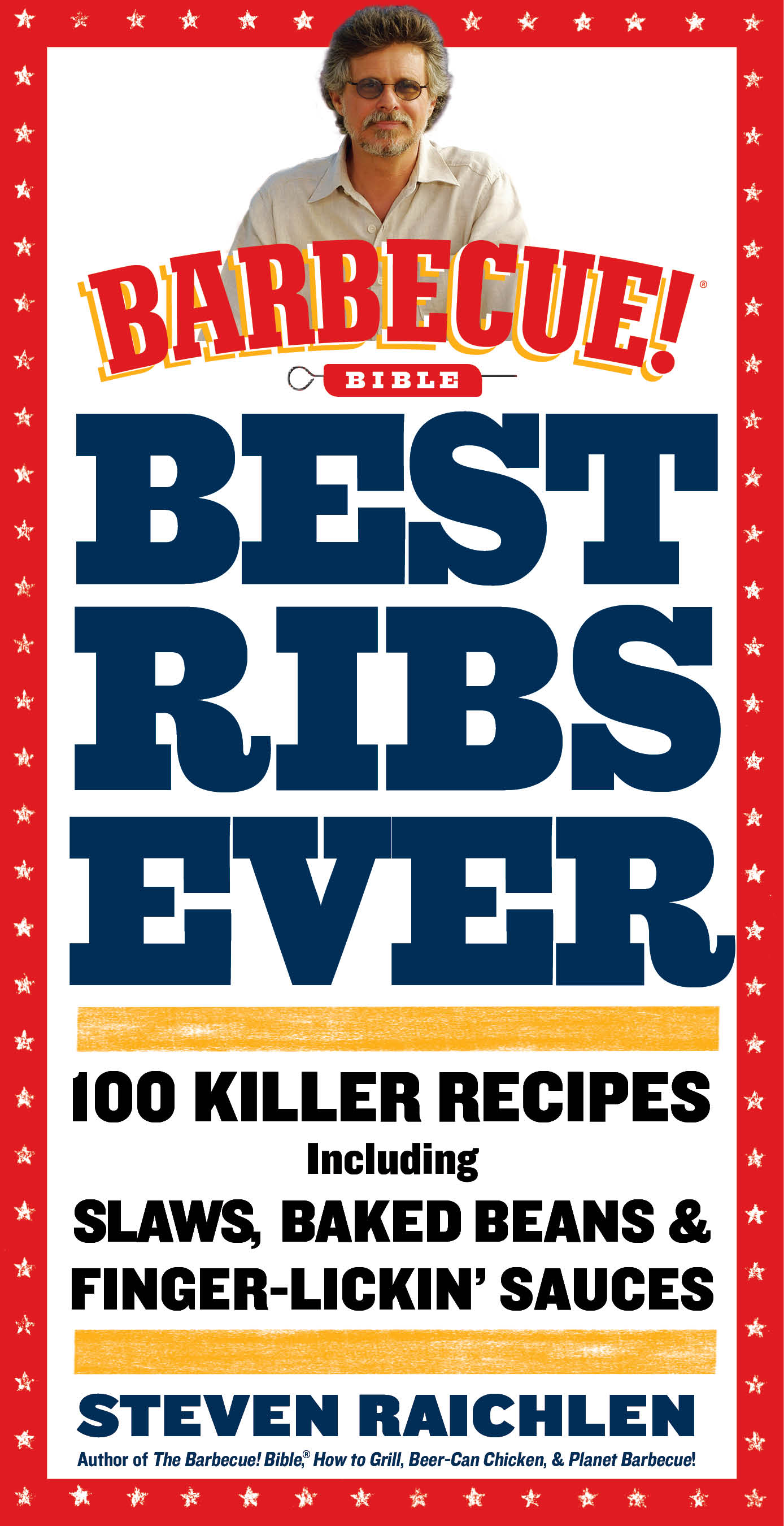

Best Ribs Ever: A Barbecue Bible Cookbook

100 Killer Recipes

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$9.99Price

$12.99 CADFormat

Format:

ebook (Digital original) $9.99 $12.99 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 25, 2012. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

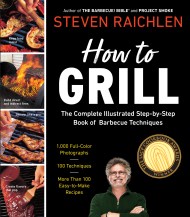

Say it loud, say it proud: the Best Ribs Ever. The perfect single-subject cookbook for every meat-loving griller, this book, formerly titled Ribs, Ribs, Outrageous Ribs, and updated with a menu chapter’s worth of new recipes, delivers a match made in BBQ heaven: 100 lip-smackingest, mouth-wateringest, crowd-pleasingest, fall-off-the-bone recipes for every kind of rib, from the diminutive, succulent baby back to that two-hands-needed Dinosaur beef rib.Best Ribs Ever celebrates the ingredient that epitomizes barbecue and inspires passion, obsession, and almost primal lust in griller and eater alike. And there’s no one better than Steven Raichlen, America’s foremost and bestselling grilling author, to preside over the religion of the rib. Here’s a bone-by-bone guide to choosing, buying, and handling ribs. Eight essential techniques for prepping and cooking. The six great live-fire methods, beginning with direct grilling to spit-roasting. Plus rubbing, saucing, mopping, resting, serving. And then the recipes: Lone Star Barrel Staves. Tandoori Ribs. Buccaneer Baby Backs with Rumbullion Barbecue Sauce. Thai Sweet Chili Ribs. Maui-Style Short Ribs. Grilled Lamb Ribs with Garlic and Mint. Cousin Dave’s Chocolate Chipotle Ribs. Plus the sides—the beans, the slaws, the potatoes—and, new to this edition, menus, like: Grilled Corn Fritters with Maple Syrup followed by Oak-Grilled Country Style Ribs followed by Grilled Lemon Pie.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Apr 25, 2012

- Page Count

- 320 pages

- Publisher

- Workman Publishing Company

- ISBN-13

- 9780761171263

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use