By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

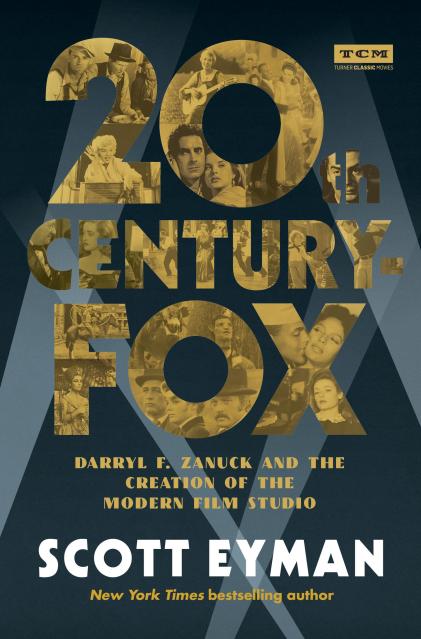

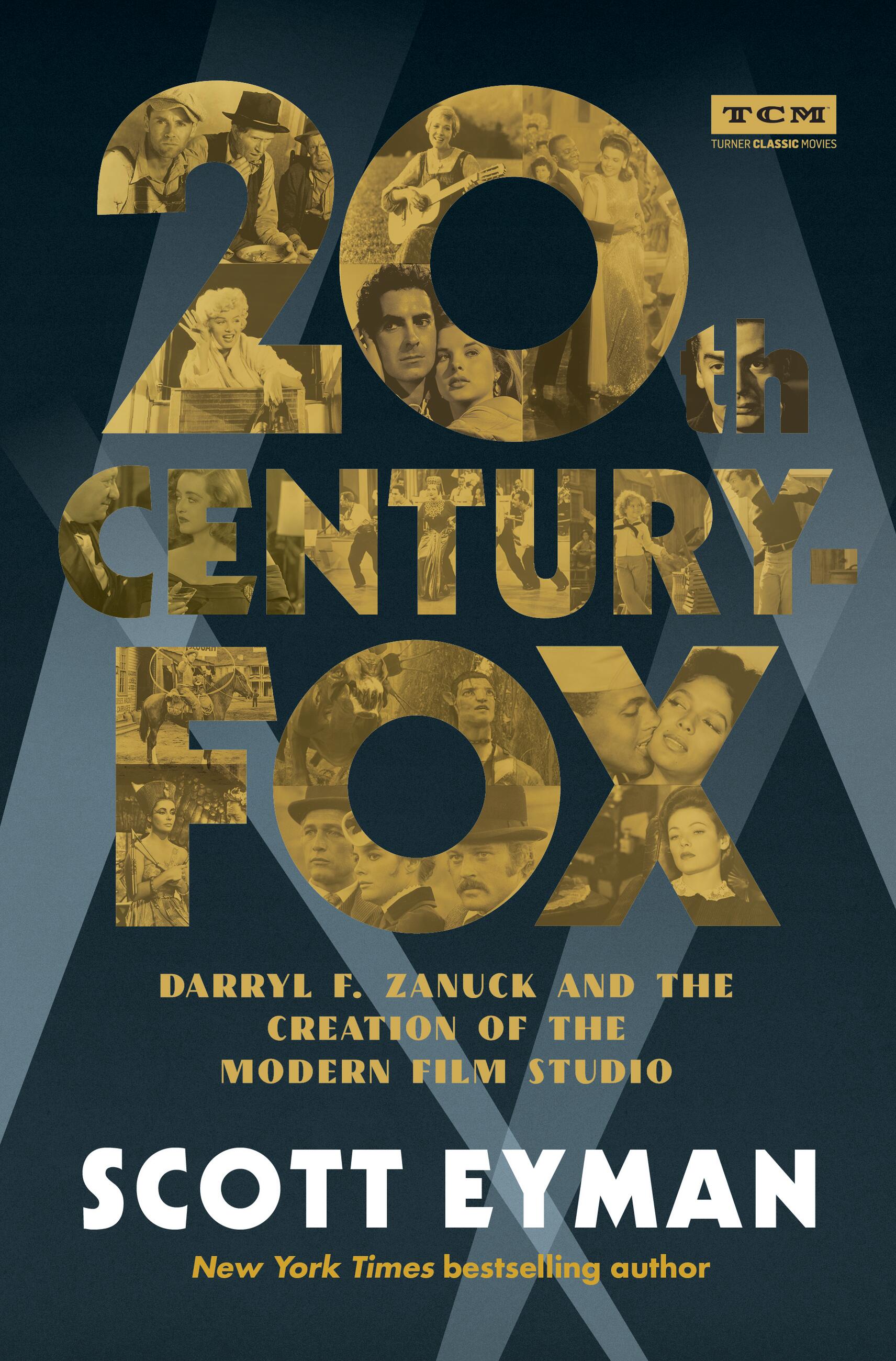

20th Century-Fox

Darryl F. Zanuck and the Creation of the Modern Film Studio

Contributors

By Scott Eyman

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Sep 21, 2021

- Page Count

- 304 pages

- Publisher

- Running Press

- ISBN-13

- 9780762470938

Price

$28.00Price

$35.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $28.00 $35.00 CAD

- ebook $14.99 $19.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $24.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 21, 2021. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

March 20, 2019 marked the end of an era — Disney took ownership of the movie empire that was Fox. For almost a century before that historic date, Twentieth Century-Fox was one of the preeminent producers of films, stars, and filmmakers. Its unique identity in the industry and place in movie history is unparalleled — and one of the greatest stories to come out of Hollywood. One man, a legendary producer named Darryl F. Zanuck, is the heart of the story. This narrative tells the complete tale of Zanuck and the films, stars, intrigue, and innovations of the iconic studio that was.

Series:

-

“There have been many studies of the great American film studios, so any new entry in the field has to supply something new — and that is precisely what Scott Eyman provides in his fascinating and well-researched volume on 20th Century Fox”Barry Forshaw, Crime Time

-

“Film historian and bestselling author Scott Eyman has done it again with 20th Century-Fox.”Danielle Solzman, Solzy At The Movies

-

"This is a lot to cover in 300 pages...but Mr. Eyman is aided immensely by his gift for pithy observation and his ability to draw a portrait with a few deft strokes."Wall Street Journal

-

"There is not, in my estimation, a better way to describe the essence of Darryl F. Zanuck than Eyman accomplishes here, as he widens the lens on Zanuck's drives, vision, and personal philosophy of life, all of which lives on in the dreams of the cinema created under his dedicated and fantastical mind."EDGE Media Network

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use