By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

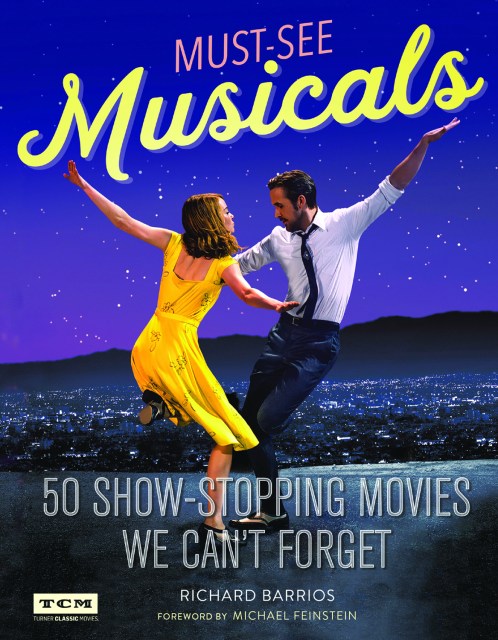

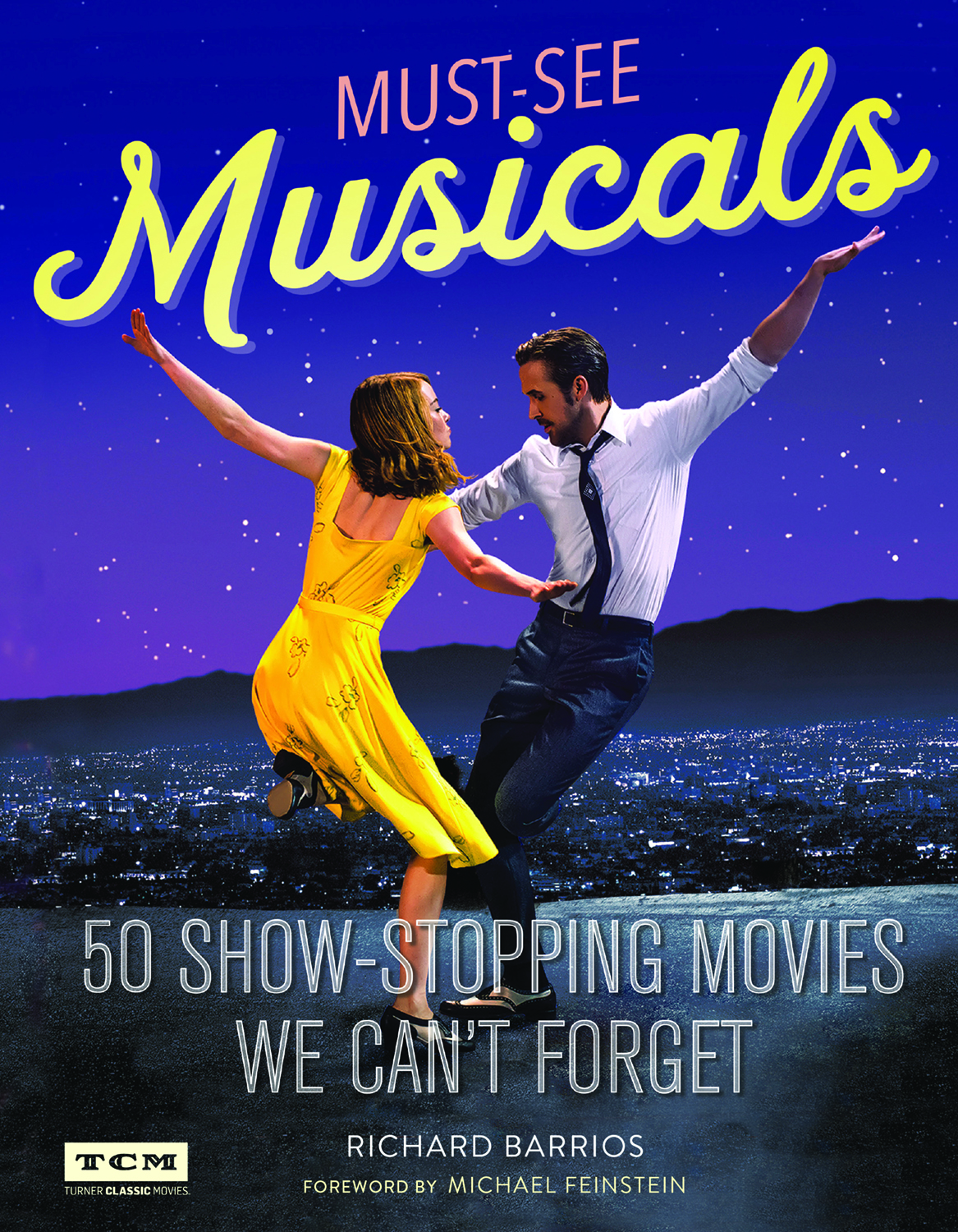

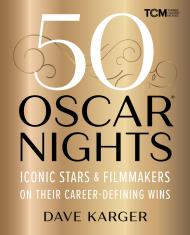

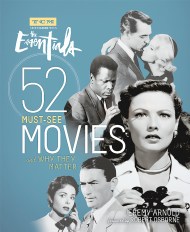

Must-See Musicals

50 Show-Stopping Movies We Can't Forget

Contributors

Foreword by Michael Feinstein

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Oct 10, 2017

- Page Count

- 264 pages

- Publisher

- Running Press

- ISBN-13

- 9780762463169

Price

$24.99Price

$32.49 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $24.99 $32.49 CAD

- ebook $13.99 $16.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 10, 2017. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Movie musicals have been a part of pop culture since films began to talk, over nine decades ago. From The Jazz Singer in 1927 all the way to La La Land in modern times, musicals have sung and danced over a vast amount of territory, thrilling audiences the entire time. More than any other type of entertainment, musicals transport us to marvelous places: a Technicolor land over the rainbow in The Wizard of Oz; a romantic ballroom where, in Top Hat, Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers dance cheek to cheek; a London theater where the Beatles perform before hysterical crowds in A Hard Day’s Night; even to a seemingly alternate reality where eager throngs still throw rice as they watch The Rocky Horror Picture Show. These titles, and many more, show us that a great musical film is a timeless joy.

Covering fifty of the best spanning the dawn of sound to the high-def present, Turner Classic Movies: Must-See Musicals — written by renowned musical historian Richard Barrios-is filled with lush illustrations as well as enlightening commentary and entertaining “backstage” stories about every one of these unforgettable films.

Series:

-

"This is a delight for anyone who loves musicals."-Manhattan Book Review

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use