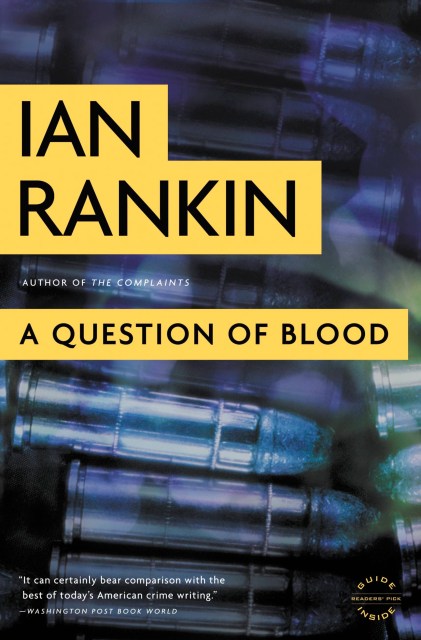

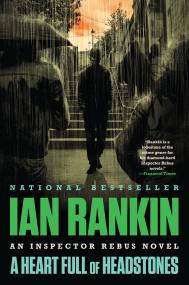

A Question of Blood

An Inspector Rebus Novel

Contributors

By Ian Rankin

Formats and Prices

Price

$24.99Format

Format:

- Trade Paperback $24.99

- ebook $10.99

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 13, 2010. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

When a former soldier and recluse murders two 17-year-old students at a posh Edinburgh boarding school, Inspector John Rebus immediately suspects there is more to the case than meets the eye.

Series:

- On Sale

- Oct 13, 2010

- Page Count

- 432 pages

- Publisher

- Back Bay Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780316099240

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use