Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

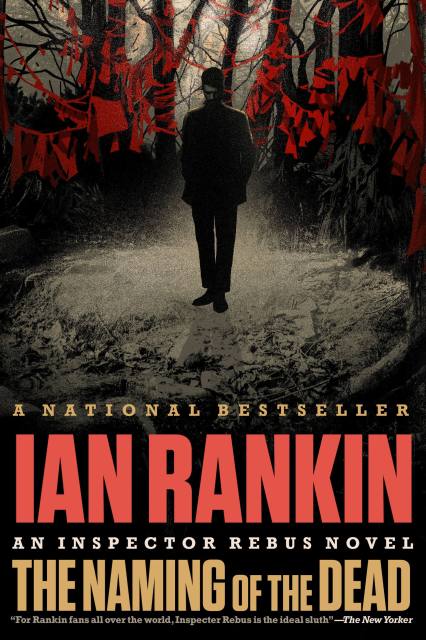

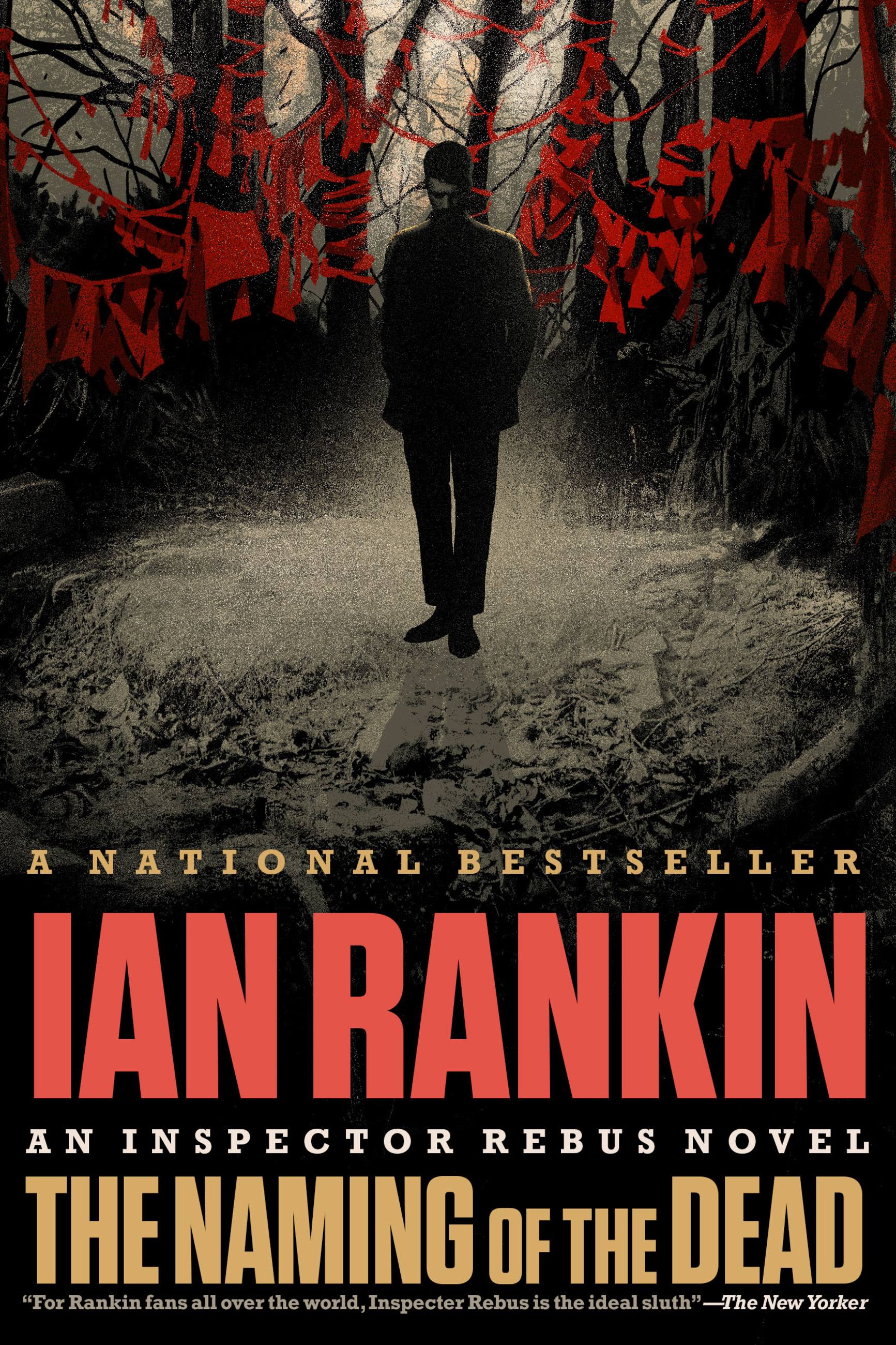

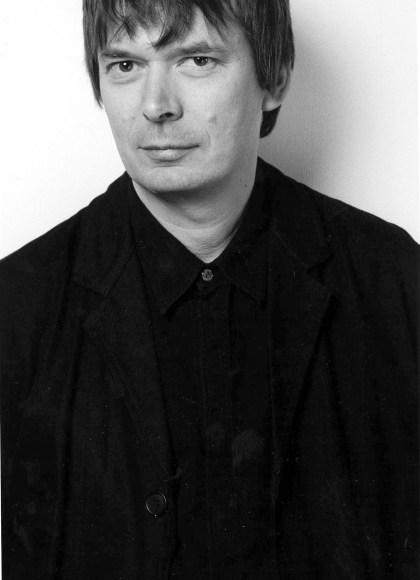

The Naming of the Dead

Contributors

By Ian Rankin

Formats and Prices

Price

$20.99Format

Format:

- Trade Paperback $20.99

- ebook $9.99

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around November 15, 2010. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

The leaders of the free world descend on Scotland for an international conference, and every cop in the country is needed for front-line duty…except one. John Rebus’s reputation precedes him, and his bosses don’t want him anywhere near Presidents Bush and Putin, which explains why he’s manning an abandoned police station when a call comes in. During a preconference dinner at Edinburgh Castle, a delegate has fallen to his death. Accident, suicide, or something altogether more sinister? And is it linked to a grisly find close to the site of the gathering? Are the world’s most powerful men at risk from a killer? While the government and secret services attempt to hush the whole thing up, Rebus knows he has only seventy-two hours to find the answers.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Nov 15, 2010

- Page Count

- 480 pages

- Publisher

- Back Bay Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780316099264

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use