Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

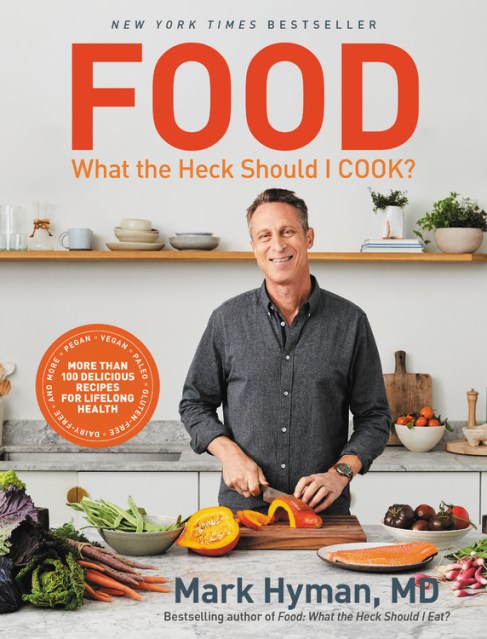

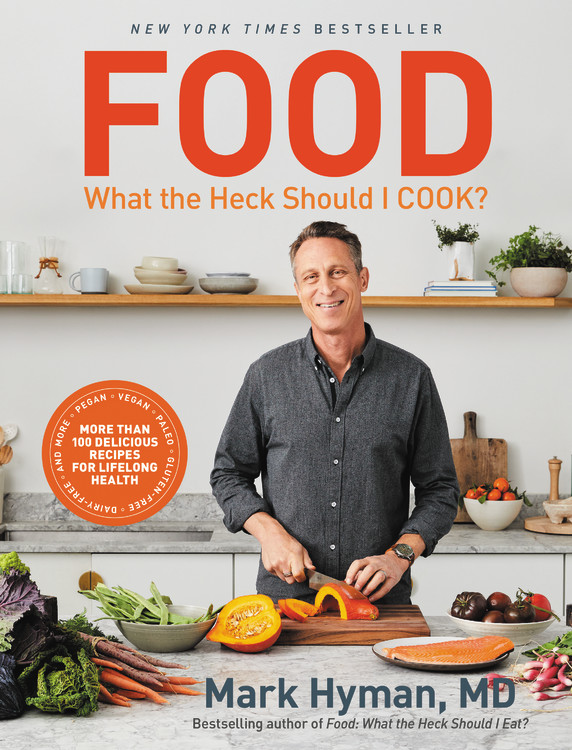

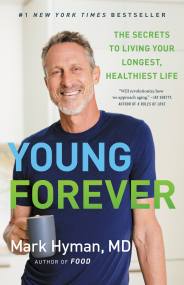

Food: What the Heck Should I Cook?

More than 100 Delicious Recipes--Pegan, Vegan, Paleo, Gluten-free, Dairy-free, and More--For Lifelong Health

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$35.00Price

$45.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $35.00 $45.00 CAD

- ebook $15.99 $20.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 22, 2019. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

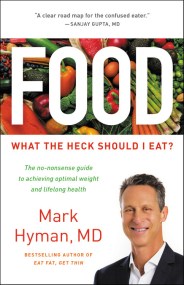

The companion cookbook to Dr. Hyman’s New York Times bestselling Food: What the Heck Should I Eat?, featuring more than 100 delicious and nutritious recipes for weight loss and lifelong health.

Dr. Mark Hyman’s Food: What the Heck Should I Eat? revolutionized the way we view food, busting long-held nutritional myths that have sabotaged our health and kept us away from delicious foods that are actually good for us. Now, in this companion cookbook, Dr. Hyman shares more than 100 delicious recipes to help you create a balanced diet for weight loss, longevity, and optimum health. Food is medicine, and medicine never tasted or felt so good.

The recipes in Food: What the Heck Should I Cook? highlight the benefits of good fats, fresh veggies, nuts, legumes, and responsibly harvested ingredients of all kinds. Whether you follow a vegan, Paleo, Pegan, grain-free, or dairy-free diet, you’ll find dozens of mouthwatering dishes, including:

- Mussels and Fennel in White Wine Broth

- Golden Cauliflower Caesar Salad

- Herbed Mini-Meatballs with Butternut Noodles

- Lemon Berry Rose Cream Cake

- and many more

With creative options and ideas for lifestyles and budgets of all kinds, Food: What the Heck Should I Cook? is a road map to a satisfying diet of real food that will keep you and your family fit, healthy, and happy for life.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Oct 22, 2019

- Page Count

- 320 pages

- Publisher

- Little Brown Spark

- ISBN-13

- 9780316453134

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use