Promotion

Shop now and save 20% on your back-to-school purchases & get free shipping on orders $45+ Use code: SCHOOL24

Oregon and Washington's Roadside Ecology

33 Easy Walks Through the Region’s Amazing Natural Areas

Contributors

By Roddy Scheer

Formats and Prices

Price

$24.95Price

$30.95 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $24.95 $30.95 CAD

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 29, 2022. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

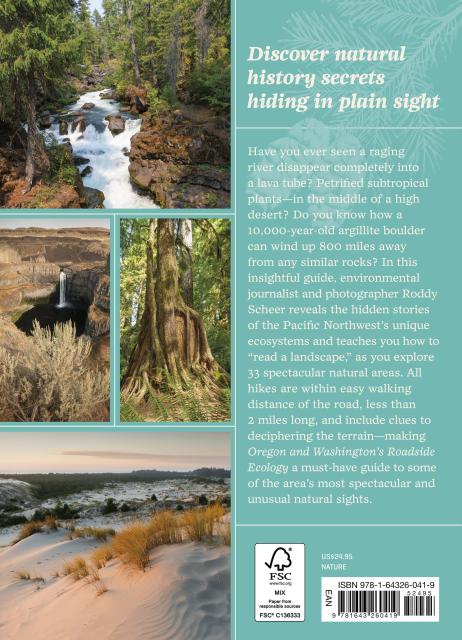

Have you ever seen a raging river disappear completely into a lava tube? Petrified subtropical plants in the middle of a high desert? Do you know how a 10,000-year-old argillite boulder can wind up 800 miles away from any similar rocks? In this insightful guide, environmental journalist and photographer Roddy Scheer reveals the hidden stories of the Pacific Northwest’s unique ecosystems and teaches you how to “read a landscape,” as you explore 33 spectacular natural areas. All hikes are within easy walking distance of the road, less than two miles long, and include clues to deciphering the terrain—making Oregon and Washington’s Roadside Ecology a must-have guide to some of the area’s most spectacular and unusual natural sights.

Genre:

-

“A must-have guide to some of the area’s most spectacular and unusual natural sights." —The Good Men Project

- On Sale

- Mar 29, 2022

- Page Count

- 368 pages

- Publisher

- Timber Press

- ISBN-13

- 9781643260419

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use