Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

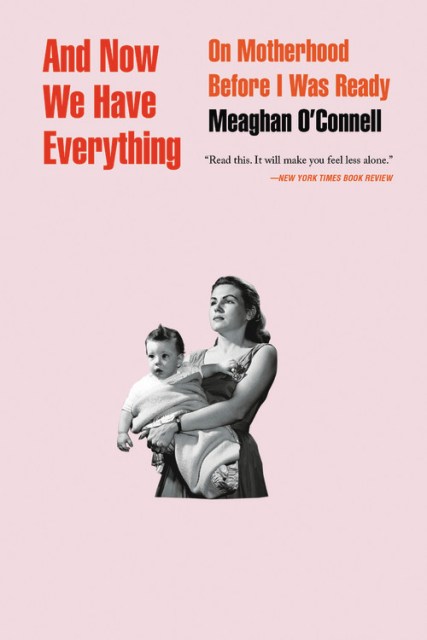

And Now We Have Everything

On Motherhood Before I Was Ready

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$16.99Price

$22.49 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $16.99 $22.49 CAD

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 16, 2019. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

A raw, funny, and fiercely honest account of becoming a mother before feeling like a grown up.

When Meaghan O’Connell got accidentally pregnant in her twenties and decided to keep the baby, she realized that the book she needed — a brutally honest, agenda-free reckoning with the emotional and existential impact of motherhood — didn’t exist. So she decided to write it herself.

And Now We Have Everything is O’Connell’s exploration of the cataclysmic, impossible-to-prepare-for experience of becoming a mother. With her dark humor and hair-trigger B.S. detector, O’Connell addresses the pervasive imposter syndrome that comes with unplanned pregnancy, the fantasies of a “natural” birth experience that erode maternal self-esteem, post-partum body and sex issues, and the fascinating strangeness of stepping into a new, not-yet-comfortable identity.

Channeling fears and anxieties that are still taboo and often unspoken, And Now We Have Everything is an unflinchingly frank, funny, and visceral motherhood story for our times, about having a baby and staying, for better or worse, exactly yourself.

Smart, funny, and true in all the best ways, this book made me ache with recognition.” — Cheryl Strayed

When Meaghan O’Connell got accidentally pregnant in her twenties and decided to keep the baby, she realized that the book she needed — a brutally honest, agenda-free reckoning with the emotional and existential impact of motherhood — didn’t exist. So she decided to write it herself.

And Now We Have Everything is O’Connell’s exploration of the cataclysmic, impossible-to-prepare-for experience of becoming a mother. With her dark humor and hair-trigger B.S. detector, O’Connell addresses the pervasive imposter syndrome that comes with unplanned pregnancy, the fantasies of a “natural” birth experience that erode maternal self-esteem, post-partum body and sex issues, and the fascinating strangeness of stepping into a new, not-yet-comfortable identity.

Channeling fears and anxieties that are still taboo and often unspoken, And Now We Have Everything is an unflinchingly frank, funny, and visceral motherhood story for our times, about having a baby and staying, for better or worse, exactly yourself.

Smart, funny, and true in all the best ways, this book made me ache with recognition.” — Cheryl Strayed

Genre:

-

"This honest, neurotic, searingly funny memoir of pregnancy and childbirth is a welcome antidote in the panicked-expectant-mothers canon -- though its gripping narrative will appeal to nonparents, too."New York Times Book Review, Editors' Choice

-

"Meaghan O'Connell writes with bracing clarity about the milk-soaked days of pregnancy and early parenthood, and I (truly) laughed and cried reading her account of crossing the great human divide. The biggest compliment of all: I used several hours of daylight childcare hours reading this book, just because I didn't want to put it down."Emma Straub, New York Times bestselling author of Modern Lovers

-

"Smart, funny, and true in all the best ways, this book made me ache with recognition of what it felt like to be a new mom (and a human)."Cheryl Strayed

-

"A stunningly insightful book."Lydia Kiesling, The Millions

-

"The harrowing, hilarious, totally honest account of parenthood we've all been waiting for. O'Connell's story is compulsively readable for parents and non-parents alike, as much about being young and unprepared for life as bringing another human into this chaotic world."Sarah Gerard, author of Sunshine State

-

"As someone who hopes to have kids someday, but has no idea what that might mean, reading this book felt like getting the first honest glimpse into that world after a lifetime of clichés."Julie Buntin, authorof Marlena

-

"As any parent knows, having a child is akin to detonating a tiny bomb in the middle of your otherwise wonderful life. O'Connell is fearless when negotiating the mess and magic of such difficult terrain, the place where fantasy goes to die and a genuine adult must rise in its stead (and function perfectly on no sleep). And Now We Have Everything is like the very best conversations, the ones you have in lowered tones at the back of a smoky bar with a trusted friend-funny, dark, and threaded with just the right amount of hope."CynthiaD'Aprix Sweeney, New York Timesbestselling author of The Nest

-

"And Now We Have Everything shows how the most normal thing in the world - having an ordinary, healthy baby after an ordinary, healthy pregnancy - means being visited with all possible extremes of pain, fear, and love. O'Connell renders this normal and horrific experience real, in both emotional sweep and brutal particulars. The question she asks is simple: What is it like? And this joyous, useful, grim book tells it straight: 'F****** awful.'"NPR

-

"It's impossible to praise this book without realizing how the words we use to describe prose often originate in the words we use to describe the experiences of the body: laid bare, warm, ecstatic, brutal. And Now We Have Everything is a stark reminder of the beating, breakable hearts of the world's mothers."AlanaMassey, author of All the Lives I Want

- Emily Gould, author of Friendship

-

"For every What to Expect When You're Expecting (and its ilk), there should be a What to Expect When You Weren't Expecting. But, strangely, there isn't, so Meaghan O'Connell has committed her experience of accidental pregnancy and motherhood to the page."Elle

-

"I began And Now We Have Everything on a Friday evening and was finished with it by Saturday afternoon--and that was with house guests to entertain and two children to keep alive! Meaghan O'Connell's honesty, humor, vulnerability, and willingness to explore motherhood in all of its messy complexities made me feel understood in a way few books do. I never wanted it to end. A necessary, brilliant debut."Edan Lepucki, New York Times bestselling author of California and Woman No. 17

-

"O'Connell's honest, heartbreaking, and hilarious book about motherhood and identity is unlike anything I've ever read. And Now We Have Everything is a smart, tell-it-like-it-is essay collection from a much-needed voice."Esmé Weijun Wang, author of The Border of Paradise

-

"Stripping away the mythical fantasies of motherhood, O'Connell delivers a poignant and funny look at what it means to be a parent in our current time. The warts-and-all examination is powerful reading for anyone with or without kids."Esquire

-

"Equal parts anthropology and autobiography, And Now We Have Everything is a rigorous and thoughtful debut (and funny, let's not forget funny) from a fiercely intelligent writer. Meaghan O'Connell has done a great service to new moms and dads: showing that anxiety and humiliation are a part of being a parent, and best confronted with humor and honesty."RumaanAlam, author of Rich and Pretty

-

"The kind of book I wished for when I was pregnant. Pulling no punches, the writing is blunt, honest...This should be required reading that your doctor hands you after you see the two pink lines on the pregnancy test."BookRiot

-

"Part memoir, part guidebook, And Now We Have Everything captures all the fears and anxieties mothers-to-be have, but still aren't allowed to say out loud. Smart, insightful, and searingly honest, Meghan O'Connell's exploration of motherhood should be on every expectant parent's baby registry."Bustle

-

"Frankly speaking, this is a must-read for anyone with a mother, anyone with a baby, anyone who knows anyone with a baby - anyone."Refinery29

-

"O'Connell isn't playing a birth story for shock value or sympathy here, nor is she doing the written equivalent of shoving cute baby pictures into strangers' faces. She's cracking open her experience, analyzing the pieces, and gluing the resulting discoveries back together with perspective and artistry. To do so is an act of generosity."LitHub

-

"And Now We Have Everything isn't a book of parenting advice, but a story of the unvarnished reality of what becoming a mother meant to one woman. And for me, that's a survival guide."Rae Nudson, Electric Literature

-

"And Now We Have Everything stretches beyond the well-worn narrative grooves of the delivery room, although O'Connell's keen observational acuity throughout those pivotal scenes is nothing short of a blessing...I am, of course, slightly bitter I didn't have this book three years ago as I stared down the barrel of motherhood myself-but I'm happy to do my due diligence, and pass it on to other moms-to-be in need."Carla Bruce-Eddings, The Rumpus

-

"[O'Connell's] account is energised by her devotion to revealing the truth... Her book is a testament, a gift to mothers who might want their realities confirmed, as well as to everyone else."R. O. Kwon, The Guardian

- On Sale

- Apr 16, 2019

- Page Count

- 240 pages

- Publisher

- Back Bay Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780316393850

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use