By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

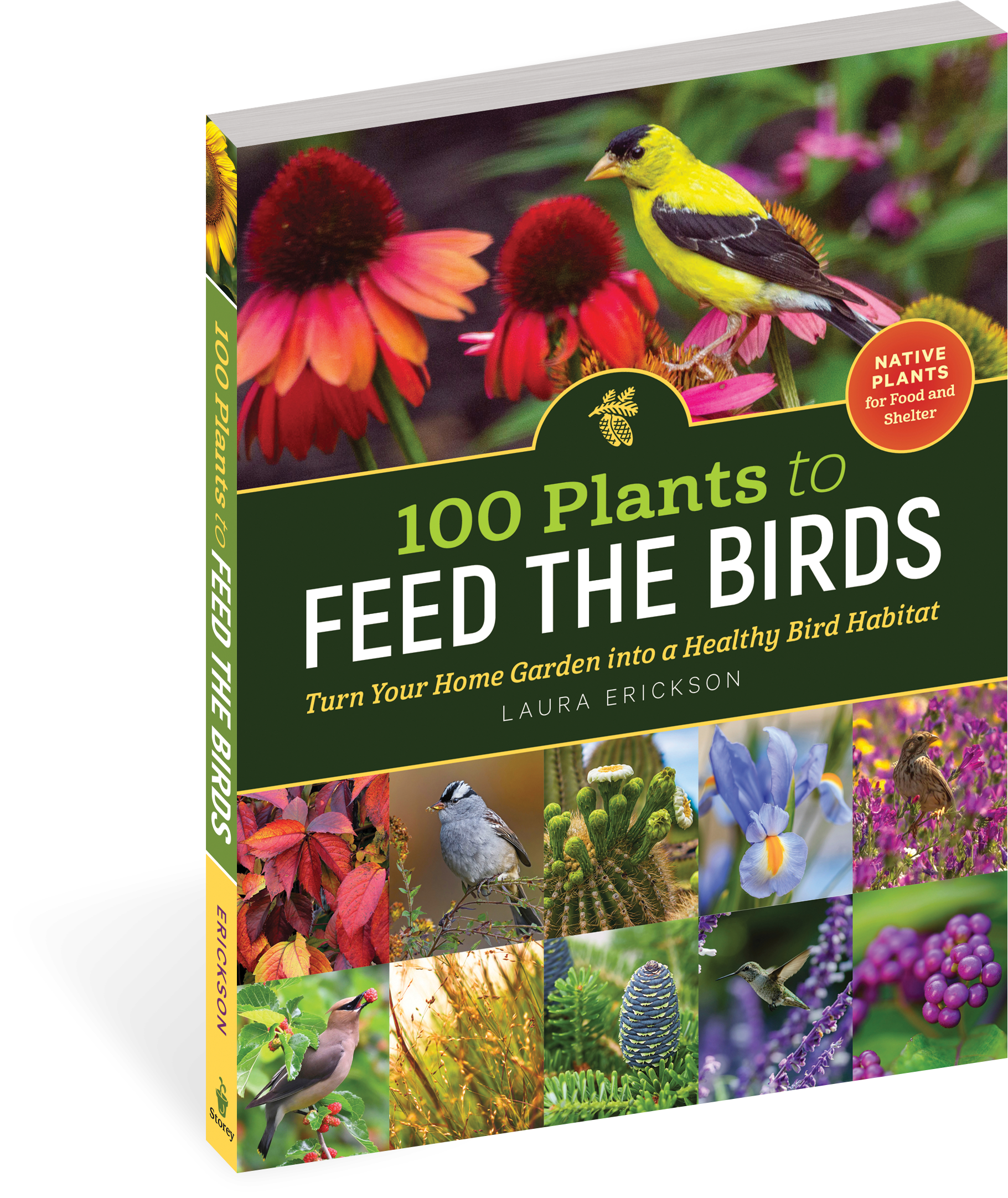

100 Plants to Feed the Birds

Turn Your Home Garden into a Healthy Bird Habitat

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Dec 20, 2022

- Page Count

- 256 pages

- Publisher

- Storey

- ISBN-13

- 9781635864380

Price

$16.99Price

$22.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $16.99 $22.99 CAD

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around December 20, 2022. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

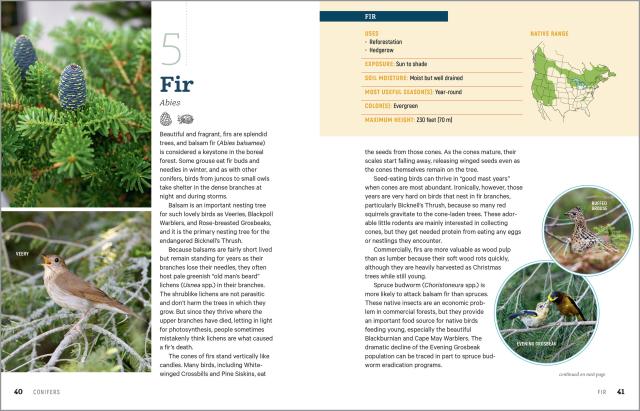

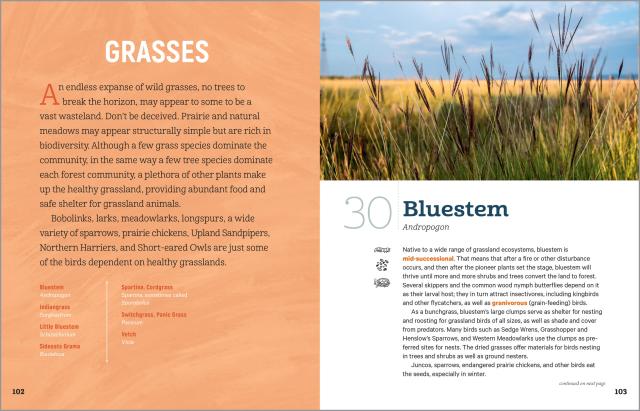

This guide offers in-depth planting and care information for 100 native plant species that feed and shelter birds all year long, including during breeding and migrating periods. Some of these plants can be added to your garden, some are helpful wild plants to avoid weeding, and some are trees that you can plant.

Color photographs and range maps give you the visual guidance you need to choose the right plants for any location in North America.

Genre:

-

“This beautifully photographed primer on bringing native species to your yard is the perfect place to start for the homeowner wondering how to attract more birds."Rebecca Minardi, Birding Magazine

-

“With its engaging text and lovely photos of plants as well as feathered friends, this book will put readers well on their way to building healthy habitats for birds.”Horticulture

-

“The best book I've seen on planting to attract birds. Packed with useful information and beautiful photos, written in a lively and accessible style, it's an essential reference for anyone who wants to improve an outdoor space anywhere in North America.” Kenn Kaufman, naturalist, author of Kingbird Highway, and editor of the Kaufman Field Guides

-

"Kudos to Laura Erickson for bringing a macro-level understanding of the world of interrelationships between birds and plants. Using native plants is the key to creating that healthy world. Informative, practical, and beautifully done, this book will help birders make backyard bird Edens wherever they live."Lillian Stokes, co-author of the Stokes Field Guide to Birds of North America

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use