Promotion

Shop now and save 20% on your back-to-school purchases & get free shipping on orders $45+ Use code: SCHOOL24

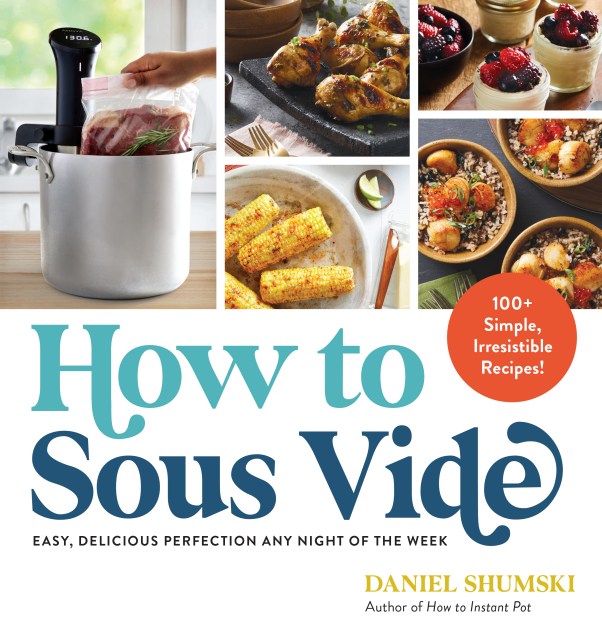

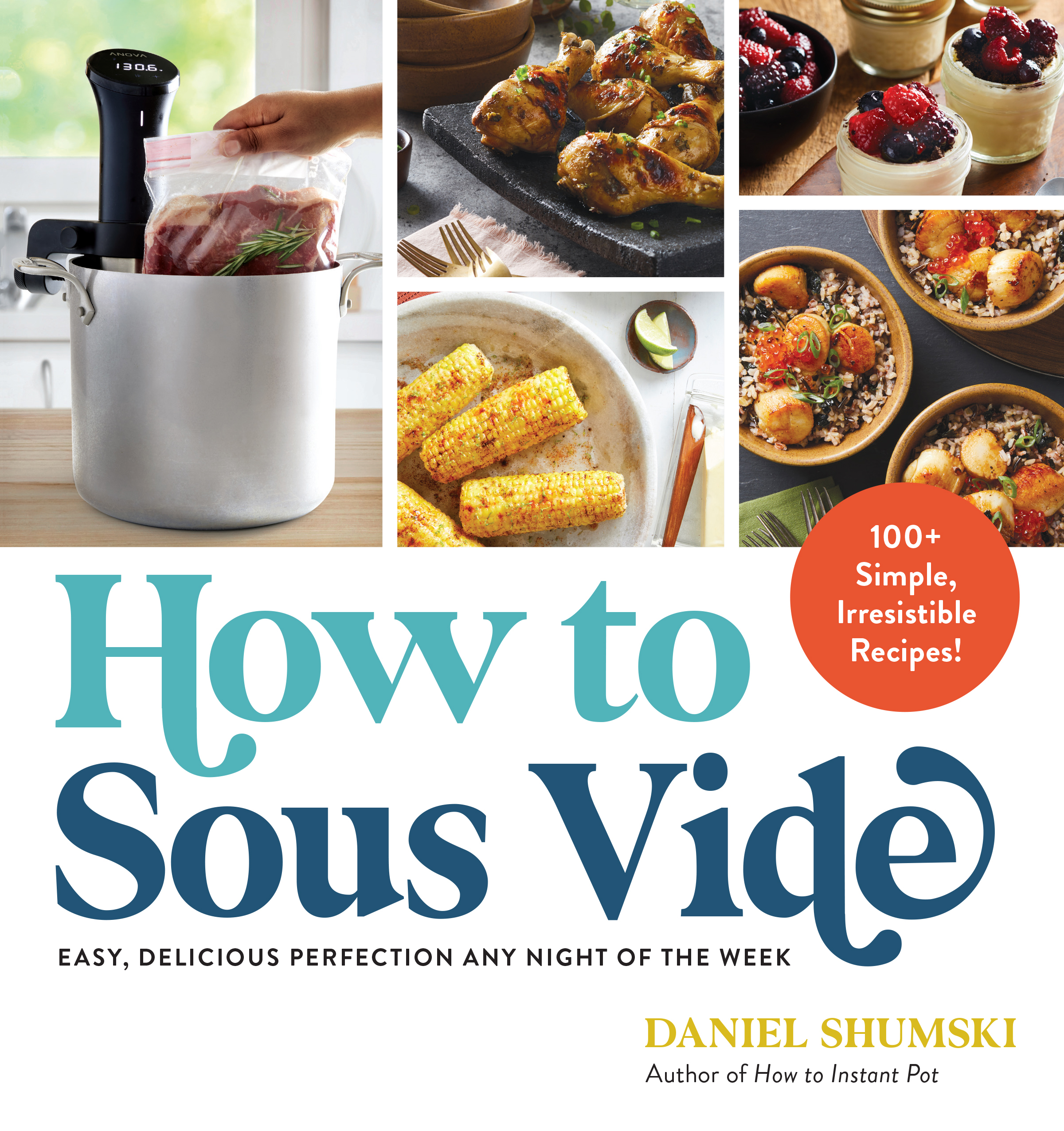

How to Sous Vide

Easy, Delicious Perfection Any Night of the Week: 100+ Simple, Irresistible Recipes

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$19.95Price

$24.95 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $19.95 $24.95 CAD

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around November 23, 2021. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

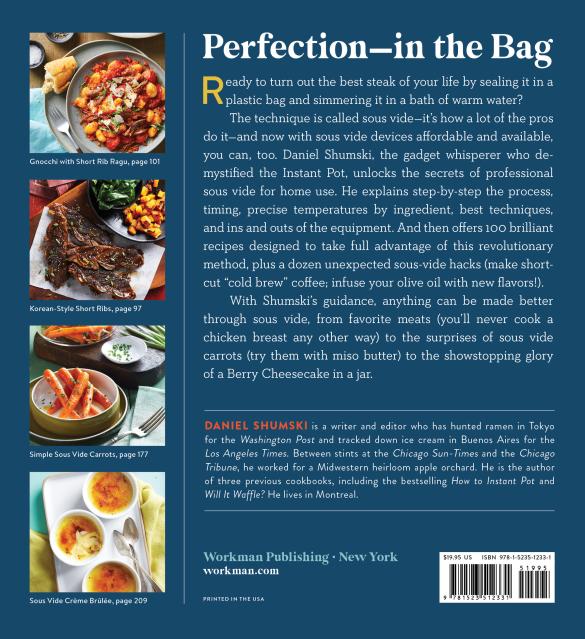

Perfection—in the bag

Ready to turn out the best steak of your life by sealing it in a plastic bag and simmering it in a bath of warm water?

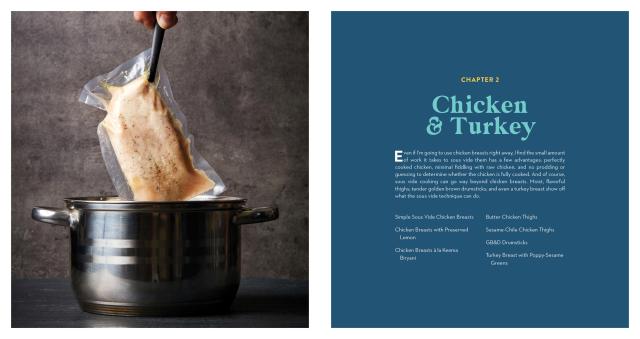

The technique is called sous vide— it’s how a lot of the pros do it—and now with sous vide devices affordable and available, you can too. Daniel Shumski, the gadget whisperer who demystified the Instant Pot, unlocks the secrets of professional sous vide for home use. He explains step by step the process, timing, precise temperatures by ingredient, best techniques, and ins and outs of the equipment. And then offers 100 brilliant recipes designed to take full advantage of this revolutionary method, plus a dozen unexpected sous-vide hacks (make short-cut “cold-brew” coffee; infuse your olive oil with new flavors!)

With Shumski’s guidance, anything can be made better through sous vide, from favorite meats (you’ll never cook a chicken breast any other way) to the surprises of sous vide carrots (try them with miso butter) to the showstopping glory of a Berry Cheesecake in a jar.

Genre:

-

“Cooking sous vide (in water with an immersion circulator) can often make dinner prep easier (and more flexible). For anyone who isn’t yet convinced, this accessible cookbook from the author of How to Instant Pot will help to demystify the whole process.” —Epicurious

“A terrific how-to... In Shumski’s estimation, this cooking method is forgiving, flavorful, and foolproof—and his enticing recipes go a long way to prove it.” —Publishers Weekly

"Sharing his enthusiasm in an approachable style, Shumski’s take on sous vide should get any cook excited to try the technique."—Library Journal

- On Sale

- Nov 23, 2021

- Page Count

- 240 pages

- Publisher

- Workman Publishing Company

- ISBN-13

- 9781523512331

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use