Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

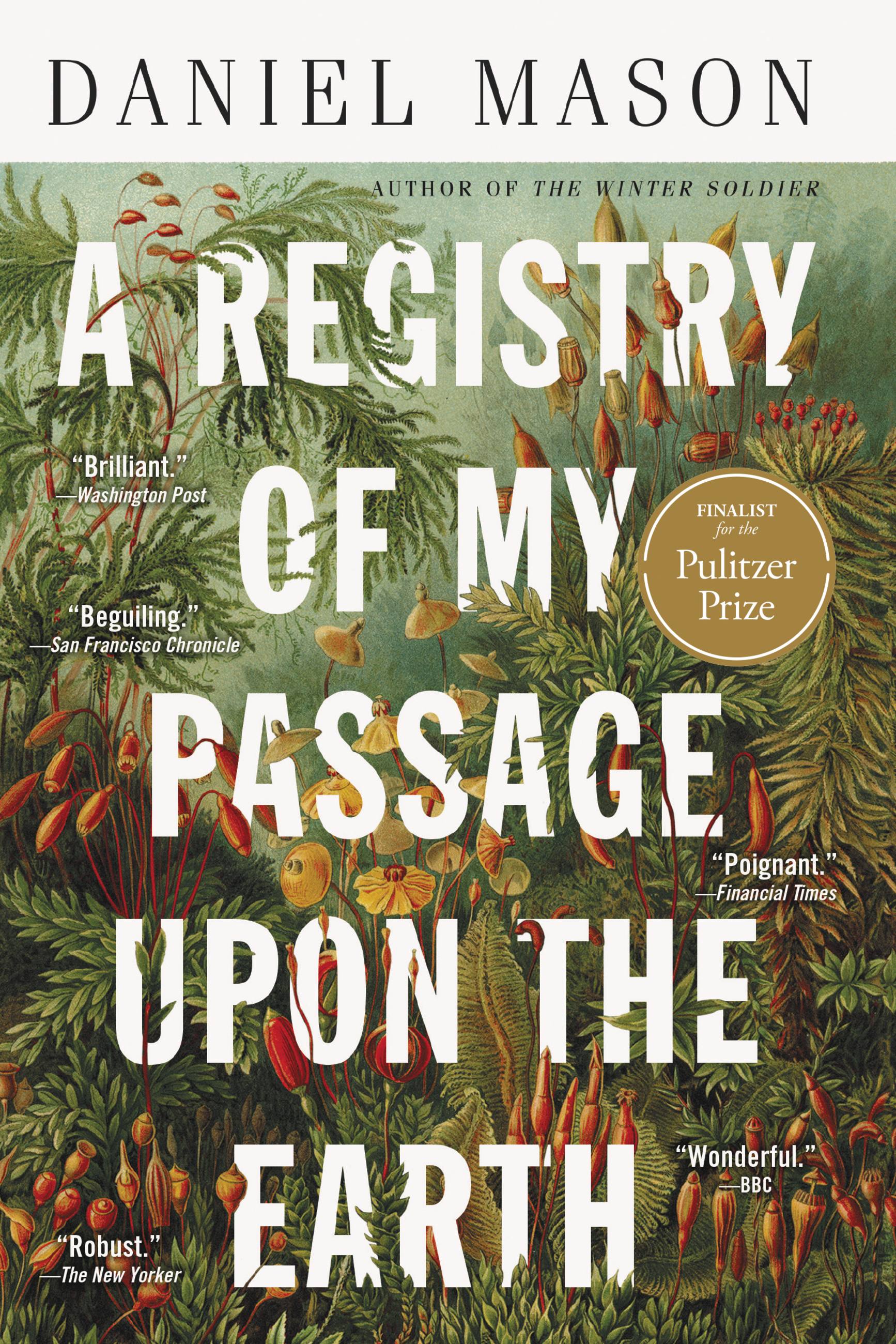

A Registry of My Passage upon the Earth

Stories

Contributors

By Daniel Mason

Formats and Prices

Price

$17.99Price

$23.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $17.99 $23.99 CAD

- ebook $10.99 $13.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around January 4, 2022. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

A Pulitzer Prize Finalist: This collection of moving short stories is “a treasure trove of lush scene setting in faraway times and places” (Alexis Burling, San Francisco Chronicle).

On a fateful flight, a balloonist makes a discovery that changes her life forever. A telegraph operator finds an unexpected companion in the middle of the Amazon. A doctor is beset by seizures, in which he is possessed by a second, perhaps better, version of himself. And in Regency London, a bare-knuckle fighter prepares to face his most fearsome opponent, while a young mother seeks a miraculous cure for her ailing son.

At times funny and irreverent, always moving and deeply urgent, these stories—among them a National Magazine Award and a Pushcart Prize winner—cap a fifteen-year project. From the Nile's depths to the highest reaches of the atmosphere, from volcano-racked islands to an asylum on the outskirts of Rio de Janeiro, these are tales of ecstasy, epiphany, and what the New York Times Magazine called the "struggle for survival . . . hand to hand, word to word," by "one of the finest prose stylists in American fiction."

A Library Journal Best Book of 2020

Genre:

-

“A collection of stories with themes of class division, the artist’s role in society and our need for love and belonging, reflecting a prowess with language and a mastery of the short form.”2021 Pulitzer Prize Committee

-

"Unique and beguiling... Mason's first short story collection is a treasure trove of lush scene setting in faraway times and places, from the wilds of England to the Malay Archipelago... A perfect and fitting pick for these seemingly endless days when science, our understanding of reality and a faint longing for human connection are so irrevocably intertwined."Alexis Burling, San Francisco Chronicle

-

"What I've found most remarkable about Mason's fiction is the quality of his revelations, his ability to unveil temperaments, habits, natures. His stories are mysteries, albeit not in the genre sense... In all of the stories, you can see Mason figuring out new strategies to get closer to the people he is writing about. Each is a portrait, each a deep dive into an individual's nature, each rooted in history."Wyatt Mason, New York Times Magazine

-

“A Registry of My Passage upon the Earth is itself something of an aesthetic miracle of found material, an extraordinarily rich and varied collection in which Mason's erudition shimmers with insight and deep feeling.”Northern California Book Award Committee

-

“Mason is particularly strong at depicting the state of mind a character works himself into when struggling with fear, uncertainty or even impostor syndrome… the subjects and settings provide a pleasing unity. The grand pleasures of fiction are all here: rich, cushioning detail; vivid characters delivering decisive action; and a sense of escape into a larger world.”John Self, The Guardian

-

"Mason conveys more in a short story than many authors manage in an entire novel."Christian Science Monitor

-

“The characters in these robust short stories, set mostly in the nineteenth century, struggle as captains of their destinies.”The New Yorker

-

"A wonderful set of period tales that offer a welcome transportive escape... conjuring a vivid world of scientific endeavor and human isolation in myriad settings."Mariella Frostrup, BBC

-

"Daniel Mason is a masterful storyteller, and these stories---the attention to history and science and all that is unknown---are nothing short of brilliant. With exquisite, mesmerizing language, he transports us to places far beyond the realm of our realities and then lands us in ways wholly intimate and moving. A Registry Of My Passage Upon the Earth is a marvel and a journey not to be missed."Jill McCorkle, New York Times bestselling author of Life After Life

-

"An enchanting cabinet of curiosities and wonders... Mason is one of our best historical novelists, creating panoramas of rich detail, propulsive plot, and artful character development... In his first story collection, he shows how quickly and completely he can immerse readers in a foreign place and time... Nine tales of human endurance, accomplishment, and epiphany told with style and brio."Kirkus Reviews (starred review)

- On Sale

- Jan 4, 2022

- Page Count

- 240 pages

- Publisher

- Back Bay Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780316477628

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use