Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

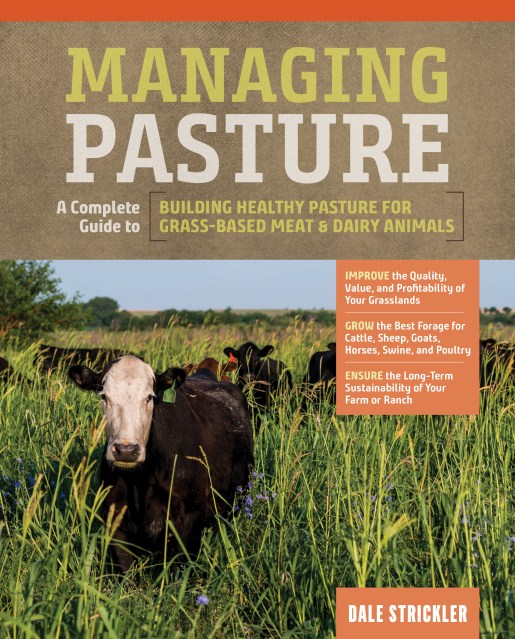

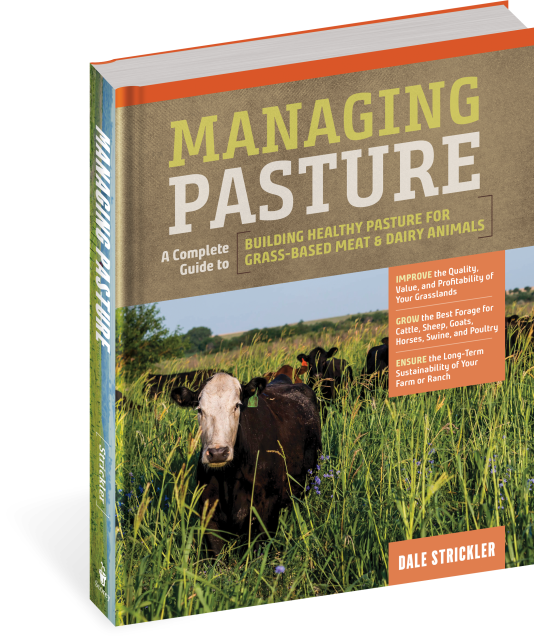

Managing Pasture

A Complete Guide to Building Healthy Pasture for Grass-Based Meat & Dairy Animals

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Apr 30, 2019

- Page Count

- 288 pages

- Publisher

- Storey

- ISBN-13

- 9781635860702

Price

$35.00Price

$45.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $35.00 $45.00 CAD

- ebook $14.99 $19.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 30, 2019. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

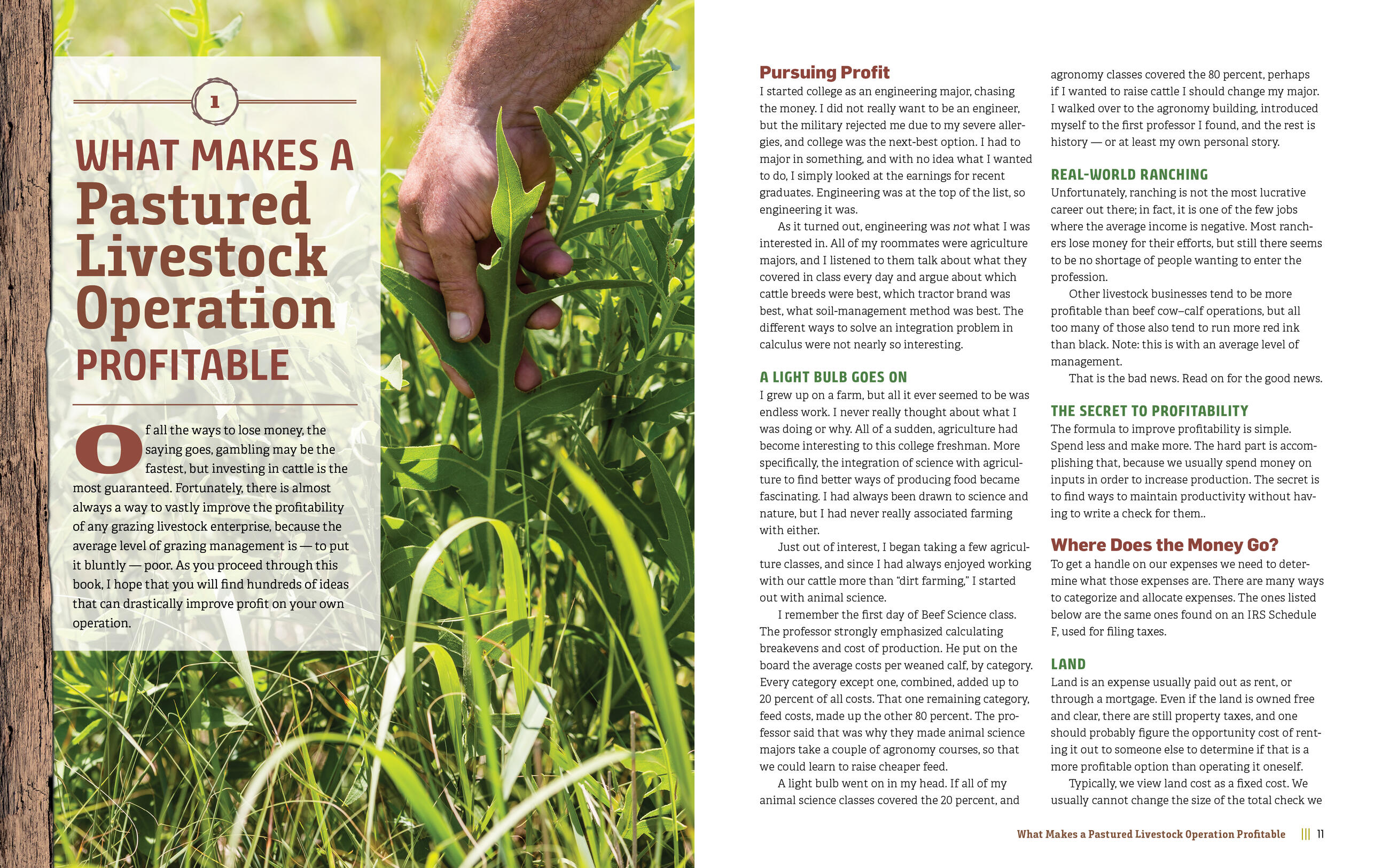

The health and profitability of grass-based livestock begins with the food they eat. In Managing Pasture, author Dale Strickler guides farmers and ranchers through the practical and ideological considerations behind caring for the land as a key part of running a successful grass-based operation, from the profitability of replacing expensive grain feed with nutrient-rich native grasses to the benefits of ecologically-minded land management.

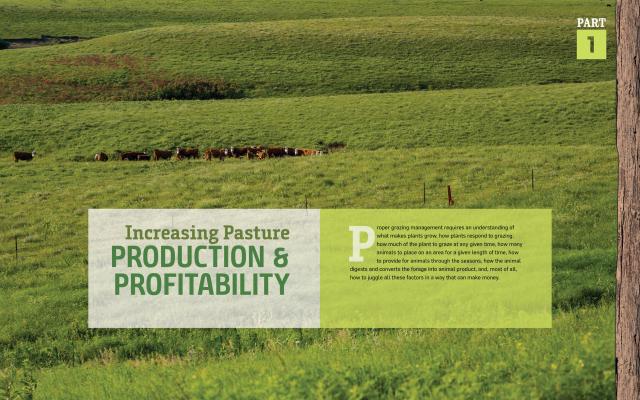

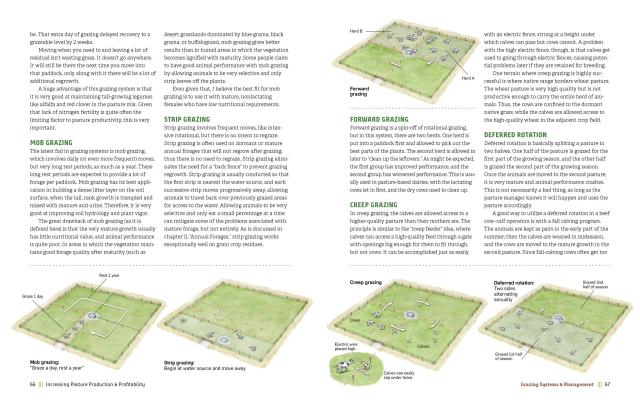

In-depth examinations of the biology and benefits of grazing plants and different grazing strategies accompany detailed plans for paddock and fencing set-ups, livestock watering, and effective methods for dealing with common pasture problems throughout the seasons, from mud to drought. For readers invested in pasture improvement strategies that offer environmental benefits beyond better meat and dairy, including carbon sequestration, erosion prevention, increased pollinator resources and wildlife habitat, and improved water quality, Managing Pasture is an approachable, accessible guide to creating and caring for the grassland that feeds animals and future generations.

In-depth examinations of the biology and benefits of grazing plants and different grazing strategies accompany detailed plans for paddock and fencing set-ups, livestock watering, and effective methods for dealing with common pasture problems throughout the seasons, from mud to drought. For readers invested in pasture improvement strategies that offer environmental benefits beyond better meat and dairy, including carbon sequestration, erosion prevention, increased pollinator resources and wildlife habitat, and improved water quality, Managing Pasture is an approachable, accessible guide to creating and caring for the grassland that feeds animals and future generations.

-

“In Managing Pasture, Dale Strickler offers plenty of first-hand guidance for both seasoned and novice livestock producers. His personal experience with what works and what doesn’t makes this a must-read for the range manager who wants to maximize profitability in a way that is best for the land and for the livestock.” — Bill Spiegel, Successful Farming

“Dale Strickler’s Managing Pasture is a testament to an agricultural awakening going on across America’s farms and ranches. Call it sustainability, or regenerative agriculture, or prescribed grazing — it’s all about managing the land, understanding how forages produce, and seeing the mutualism that exists between livestock and the land. There are amazing rewards to be found where farmers work with nature, not against it. If you want to understand why sustainable practices work, read this book. —Victoria G. Myers, Progressive Farmer

“Dale Strickler has written a comprehensive guide to what actually matters in pasture management, with enough humor woven throughout to make it an enjoyable, as well as valuable, read. If you are serious about growing and utilizing productive, high-quality pasture, this book should be on your shelf.” — Jim Gerrish, American GrazingLands Services, LLC