By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

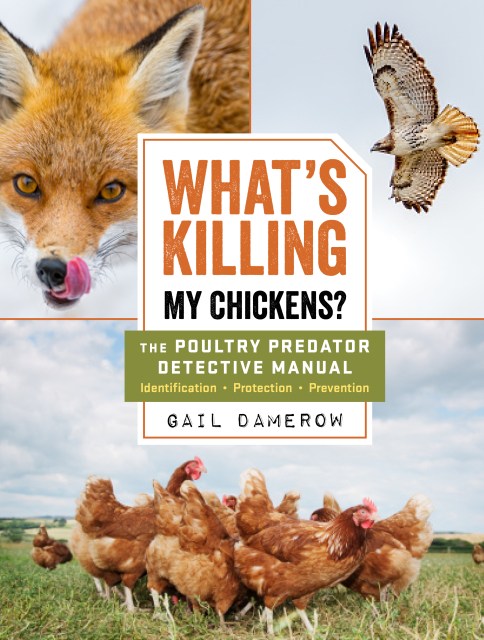

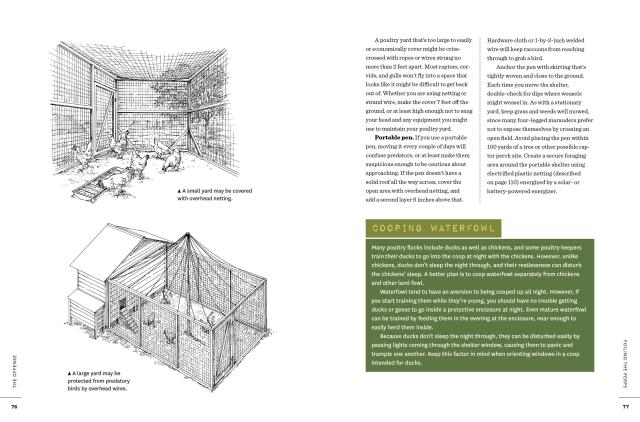

What’s Killing My Chickens?

The Poultry Predator Detective Manual

Contributors

By Gail Damerow

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Dec 10, 2019

- Page Count

- 272 pages

- Publisher

- Storey

- ISBN-13

- 9781612129099

Price

$19.95Price

$26.95 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $19.95 $26.95 CAD

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around December 10, 2019. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

-

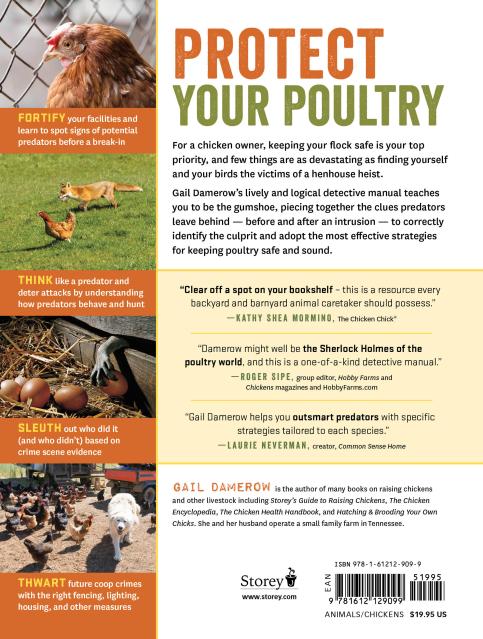

“Interspersed with compelling, often humorous, anecdotes from the author’s own close encounters and near misses with poultry predators, this book encourages responsibility and preparedness in protecting flocks from other animals that naturally find poultry attractive.” — Kathy Shea Mormino, The Chicken Chick®

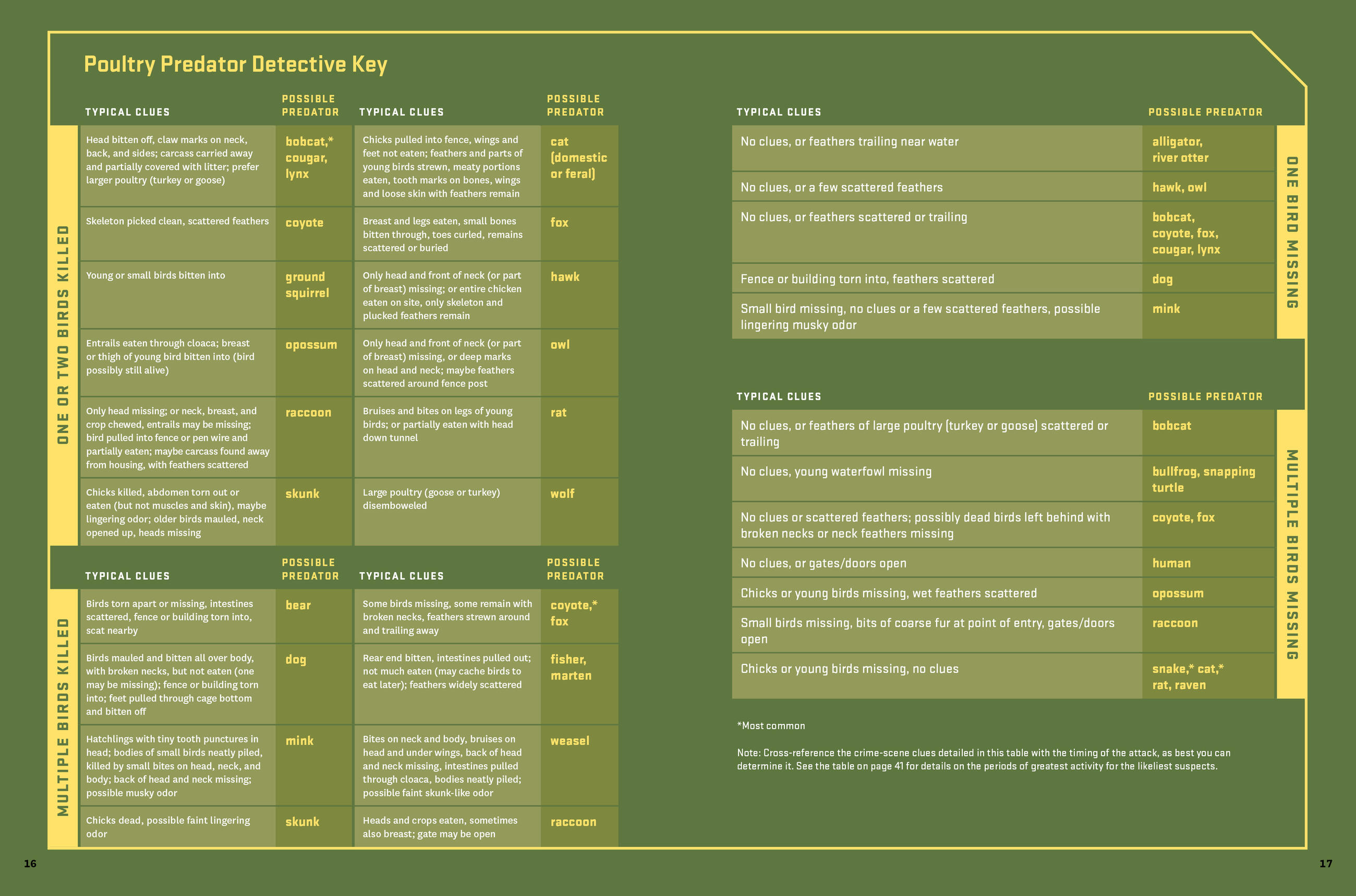

“Finally, a well-thought-out and balanced approach to protecting your flock from predators. Gail Damerow helps you ID the perps with detailed images, charts, and descriptions. Then she helps you outsmart them with specific strategies tailored to each species.” — Laurie Neverman, creator, Common Sense Home

"Gail Damerow might well be the Sherlock Holmes of the poultry world, and What’s Killing My Chickens? is a one-of-a-kind ‘detective manual’ that every chicken keeper needs to read. Through the author’s insights, flock owners can figure out what predators to watch for and how to guard against them.”

— Roger Sipe, Group Editor, Hobby Farms and Chickens magazines and HobbyFarms.com

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use