By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

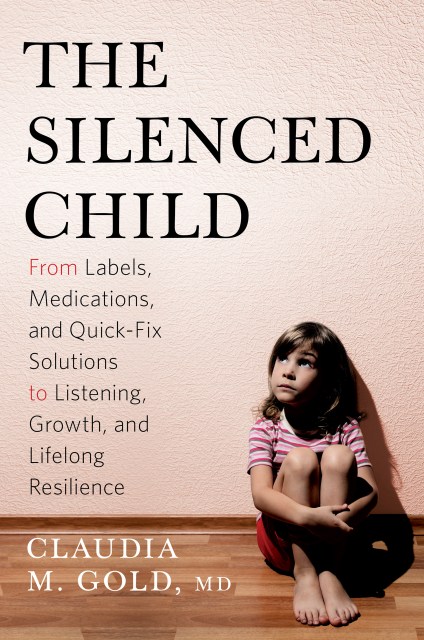

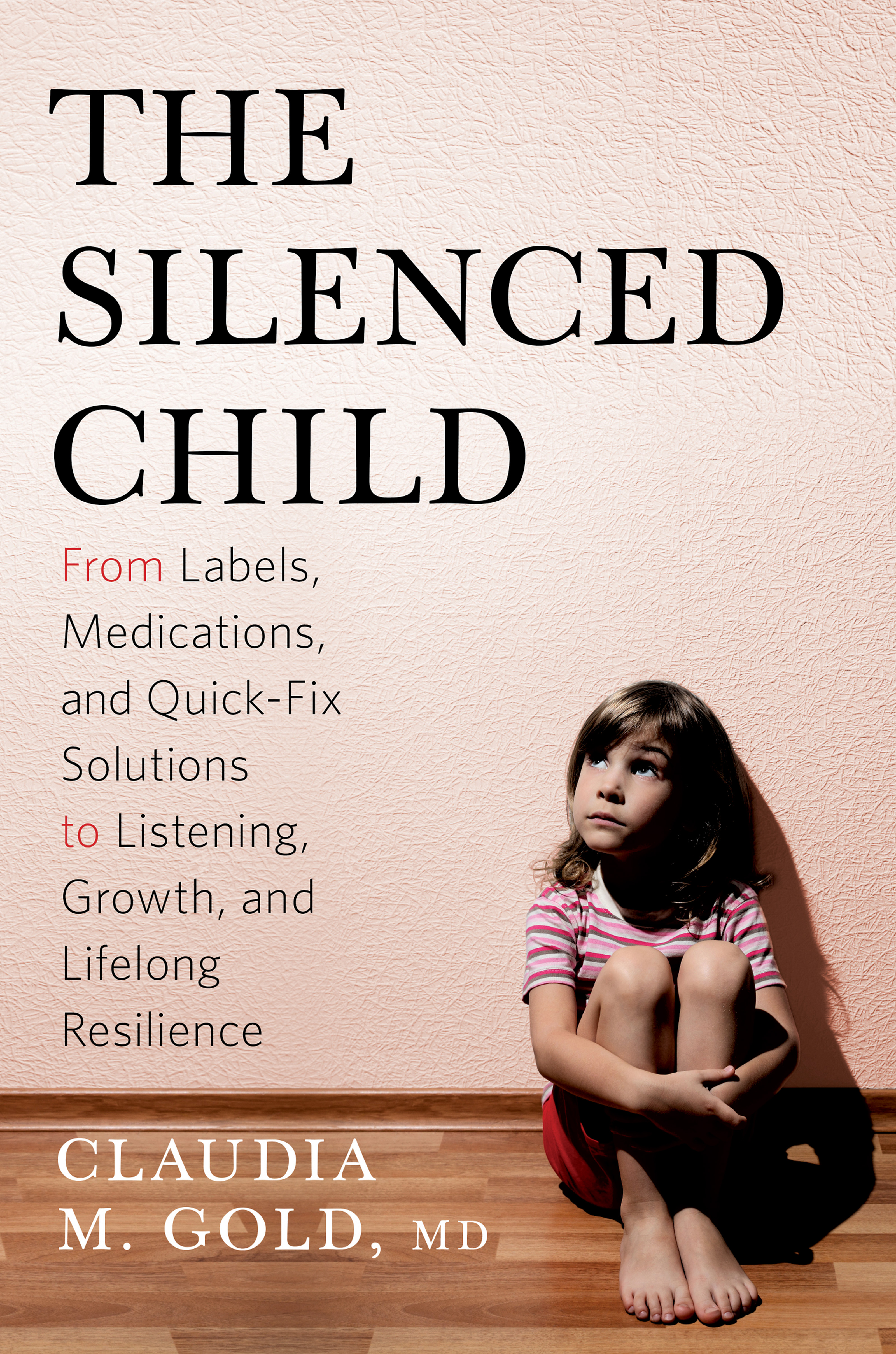

The Silenced Child

From Labels, Medications, and Quick-Fix Solutions to Listening, Growth, and Lifelong Resilience

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- May 3, 2016

- Page Count

- 272 pages

- Publisher

- Balance

- ISBN-13

- 9780738218403

Price

$17.99Price

$22.99 CADFormat

Format:

ebook $17.99 $22.99 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 3, 2016. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Praise for Keeping Your Child in Mind:

“A very useful, thoughtful book. It lays out the best thinking of our time to help parents make decisions about nurturing their child’s development.” — T. Berry Brazelton, MD, professor of Pediatrics, Emeritus Harvard Medical School

Genre:

Series:

-

Advance Praise for The Silenced Child

"This poignant book is a paean to patience, carefulness, and attentiveness—rare commodities in a digital age. It is an urgent call to action for a medical world dominated by biology and statistics. In arguing that attachment and healing take time, Claudia Gold creates a manifesto for wiser family relations, demonstrating with elegant simplicity how we can realize more productively the love we already feel for our children."

—Andrew Solomon, author of FAR FROM THE TREE

"Brazelton's To Listen to a Child, and later, his "Touchpoints" books, taught millions of parents, pediatricians and teachers that children's behavior has much to tell us, if only we learn to listen to it. In her important new book, Dr. Gold describes the ways in which children and parents have been silenced and shows us how to rescue the irreplaceable and uniquely human capacity to listen from the misguided efforts to categorize children and automate the art of caring for them."

—Joshua D Sparrow MD Director, Brazelton Touchpoints Center, Associate Professor of Psychiatry, Part-time, Harvard Medical School

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use