By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

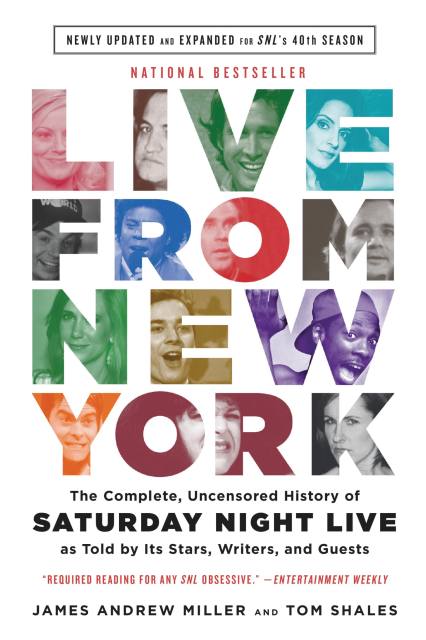

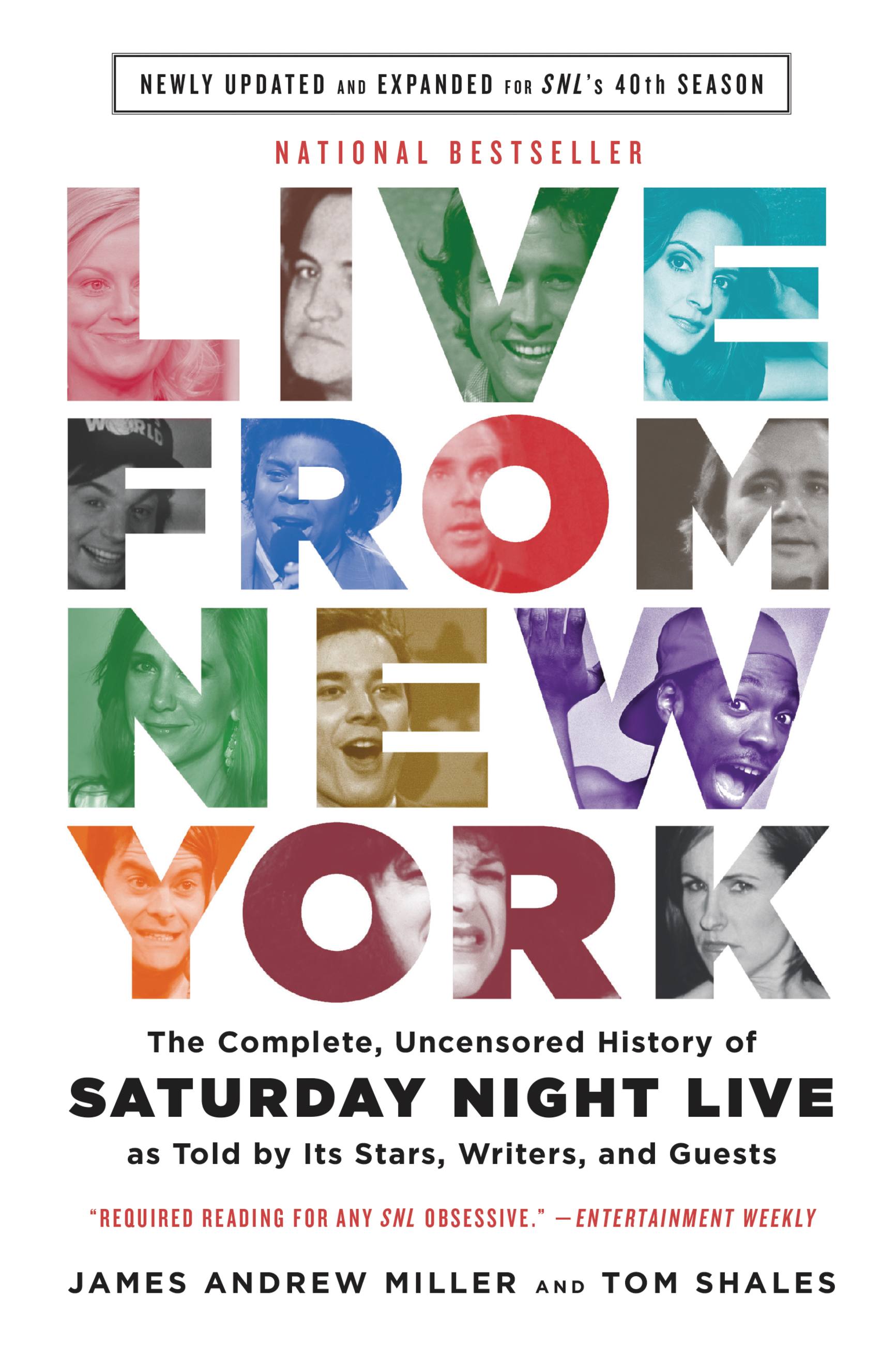

Live From New York

The Complete, Uncensored History of Saturday Night Live as Told by Its Stars, Writers, and Guests

Contributors

By Tom Shales

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Sep 9, 2014

- Page Count

- 800 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown and Company

- ISBN-13

- 9780316295079

Price

$13.99Price

$17.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $13.99 $17.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $24.99 $31.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 9, 2014. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

When first published to celebrate the 30th anniversary of Saturday Night Live, Live from New York was immediately proclaimed the best book ever produced on the landmark and legendary late-night show. In their own words, unfiltered and uncensored, a dazzling galaxy of trail-blazing talents recalled three turbulent decades of on-camera antics and off-camera escapades.

Now decades have passed, and bestselling authors James Andrew Miller and Tom Shales have returned to Studio 8H. Over more than 100 pages of new material, they raucously and revealingly take the SNL story up to the present, adding a constellation of iconic new stars, surprises, and controversies.

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use