Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

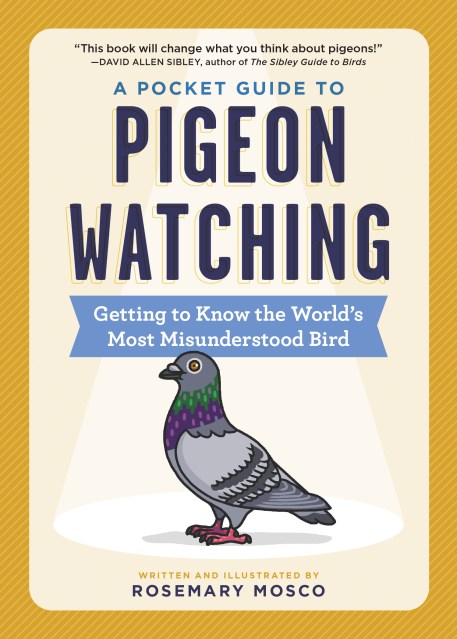

A Pocket Guide to Pigeon Watching

Getting to Know the World's Most Misunderstood Bird

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$14.99Price

$19.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $14.99 $19.99 CAD

- ebook $9.99 $12.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 26, 2021. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Part field guide, part history, part ornithology primer, and altogether fun.

Fact: Pigeons are amazing, and until recently, humans adored them. We’ve kept them as pets, held pigeon beauty contests, raced them, used them to carry messages over battlefields, harvested their poop to fertilize our crops—and cooked them in gourmet dishes. Now, with The Pocket Guide to Pigeon Watching, readers can rediscover the wonder. Equal parts illustrated field guide and quirky history, it covers behavior: Why they coo; how they flock; how they preen, kiss, and mate (monogamously); and how they raise their young (on chunky pigeon milk). Anatomy and identification, from Birmingham Roller to the American Giant Runt to the Scandaroon. Birder issues, like what to do if you find a baby pigeon stranded in the park. And our lively shared story together, including all the things we’ve taught them—Ping-Pong, for example. “Rats with wings?” Think again.

Pigeons coo, peck and nest all over the world, yet most of us treat them with indifference or disdain. So Rosemary Mosco, a bird-lover, science communicator, writer, and cartoonist (and co-author of The Atlas Obscura Explorer’s Guide for the World’s Most Adventurous Kid) is here to give the pigeon’s image a makeover, and to help every town- and city-dweller get closer to nature by discovering the joys of birding through pigeon-watching.

Genre:

-

“This book will change what you think about pigeons! With loads of eye-opening pigeon science, delivered in playful and engaging style by Rosemary Mosco's text and illustrations, A Pocket Guide to Pigeon Watching will help you gain a whole new appreciation of these smart, savvy, and adaptable birds whose lives are so intertwined with ours.”

—David Allen Sibley, author of The Sibley Guide to Birds

“Crammed with witty writing and charming cartoons, this cute book is a fun and entertaining invitation into the fascinating world of pigeons”

—Forbes

"Mosco...has written the most perfect of popular science titles, one that teaches readers everything about a topic in an accessible, funny, and charming manner. A must-read for bird lovers and urban wildlife watchers."

—Booklist, STARRED review

“We scorn pigeons for their commonness, but their ubiquity speaks to their talents. Past civilizations domesticated them and brought them wherever they went, for pigeons were loved and prized—as messengers, as producers of fertilizer, as meat on the plate. With her trademark wit and artistic charms, Mosco gives us a hundred reasons to rekindle the love affair. A Pocket Guide to Pigeon Watching is part field guide, part history, part ornithology primer, and altogether fun!”

—Mary Roach, New York Times bestselling author of Stiff and Grunt

"So joyful that it’s almost effervescent, A Pocket Guide to Pigeon Watching will convert even the grumpiest pigeon skeptics into being, at the very least, pigeon-curious. Readers will never hear the cooing in a city park or watch a preening flock of pigeons the same way again."

—Foreward Reviews

“A gifted communicator, Rosemary Mosco makes every science subject both fascinating and fun—as they should be. This delightful look at the world of pigeons is a treasure.”

—Kenn Kaufman, editor of Kaufman Field Guides

“A Pocket Guide to Pigeon Watching is my favorite kind of book: one that teaches you everything you could want to know about a single fascinating topic in a way that is accessible, charming, and hilarious.”

—Ryan North, New York Times bestselling author of How to Invent Everything

"Sparkling, witty prose, loaded with relatable pop-culture references and enhanced with charming cartoons, A Pocket Guide to Pigeon Watching is a seductive draw into the multilayered world of pigeons. This little book will sneak up and drop a load of solid ornithology on the unsuspecting reader."

—Julie Zickefoose, author of Saving Jemima: Life and Love with a Hard-luck Jay

- On Sale

- Oct 26, 2021

- Page Count

- 240 pages

- Publisher

- Workman Publishing Company

- ISBN-13

- 9781523511341

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use