Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

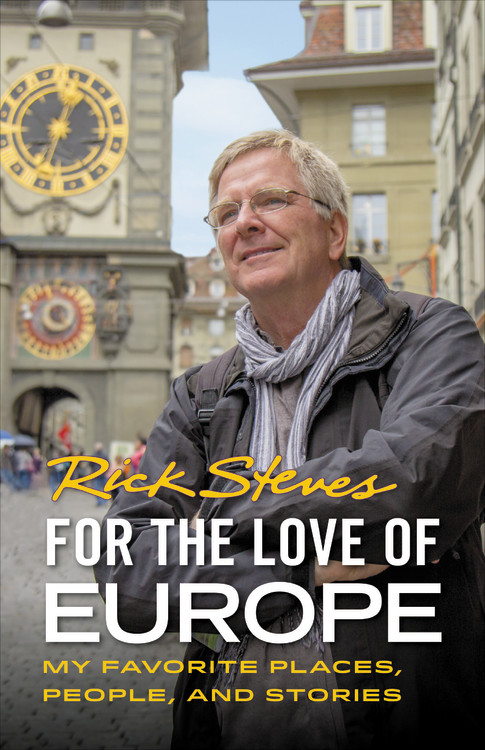

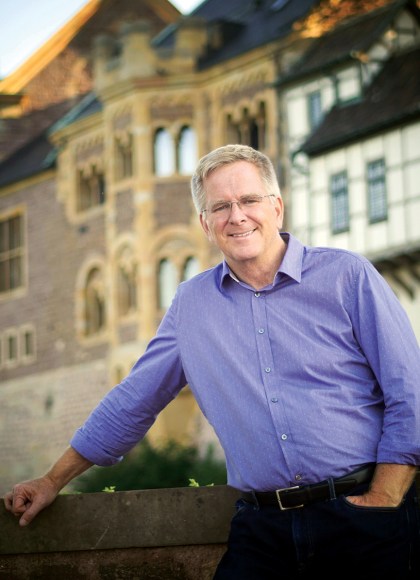

For the Love of Europe

My Favorite Places, People, and Stories

Contributors

By Rick Steves

Formats and Prices

Price

$23.99Price

$29.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $23.99 $29.99 CAD

- ebook $16.99 $21.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around July 7, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Join Rick as he's swept away by a fado singer in Lisbon, learns the dangers of falling in love with a gondolier in Venice, and savors a cheese course in the Loire Valley. Contemplate the mysteries of centuries-old stone circles in England, dangle from a cliff in the Swiss Alps, and hear a French farmer's defense of foie gras.

With a brand-new, original introduction from Rick reflecting on his decades of travel, For the Love of Europe features 100 of the best stories published throughout his career. Covering his adventures through England, France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, the Netherlands, Spain, and more, these are stories only Rick Steves could tell.

Winner of the 2022 Society of American Travel Writers' Lowell Thomas Travel Journalism Award: Best Travel Book, Silver

Genre:

- On Sale

- Jul 7, 2020

- Page Count

- 416 pages

- Publisher

- Rick Steves

- ISBN-13

- 9781641711319

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use