Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

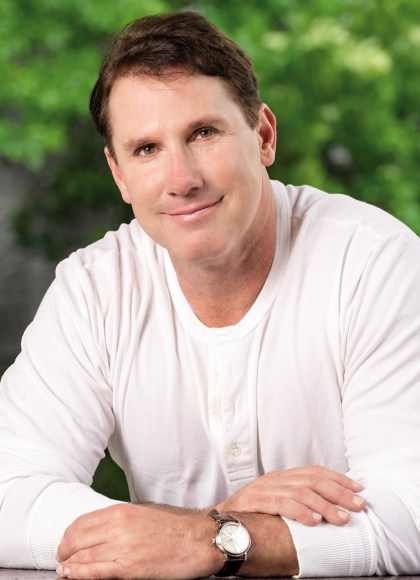

Three Weeks with My Brother

Contributors

By Micah Sparks

Formats and Prices

Price

$16.99Price

$22.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $16.99 $22.99 CAD

- ebook $9.99 $12.99 CAD

- Hardcover (Large Print) $35.00 $45.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Audiobook CD (Unabridged) $15.00 $17.00 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around June 1, 2021. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

As moving as his bestselling works of fiction, Nicholas Sparks's unique memoir, written with his brother, chronicles the life-affirming journey of two brothers bound by memories, both humorous and tragic. In January 2003, Nicholas Sparks and his brother, Micah, set off on a three-week trip around the globe. It was to mark a milestone in their lives, for at thirty-seven and thirty-eight respectively, they were now the only surviving members of their family.

Against the backdrop of the wonders of the world and often overtaken by their feelings, daredevil Micah and the more serious, introspective Nicholas recalled their rambunctious childhood adventures and the tragedies that tested their faith. And in the process, they discovered startling truths about loss, love, and hope.

Narrated with irrepressible humor and rare candor, and including personal photos, Three Weeks with My Brother reminds us to embrace life with all its uncertainties . . . and most of all, to cherish the joyful times, both small and momentous, and the wonderful people who make them possible.

Includes a Reading Group Guide.

Genre:

-

"Refreshingly honest and perceptive . . . Weaving in vignettes of tenderness and loss with travelogue-like observations . . . the brothers cover the crucial moments in a life full of familial love and tragedy."Publishers Weekly

-

"A deeply personal story of family and familial bonds . . . an entertaining blend of travelogue and memoir, but most of all it's the story of two brothers' relationship with each other."Greenville News (SC)

-

"A life-changing trip . . . of reminiscing, sharing, and learning."New York Daily News

-

"Poignant, funny, and ultimately life-affirming . . . Fans of Nicholas Sparks's novels may be surprised to learn that the author's life has known the same emotional turmoil he brings so vividly to life in his fiction."BookPage

-

"An incredible story of two brothers who fit each other like two pieces of a puzzle . . . a heartfelt tale of two brothers and a family who conquered the world in their own special way . . . The finale will make everyone want to beam a thousand-watt smile right along with them."MyShelf.com

-

"This is a rare opportunity for readers to get to know a favorite author as Nicholas reveals the inspirations for his fiction. A mustread for Sparks fans as well as a treat for those who want to find out what makes a family strong."Booklist

-

"Compelling . . . unprecedented . . . This unforgettable memoir will touch your heart and your spirit, and will make you look at Sparks's writings, and your own life, with a fresh perspective."Large Print Reviews

- On Sale

- Jun 1, 2021

- Page Count

- 400 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9781538705452

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use