Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

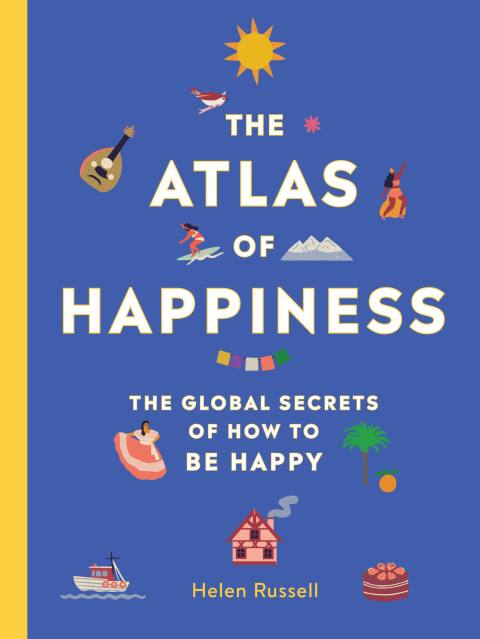

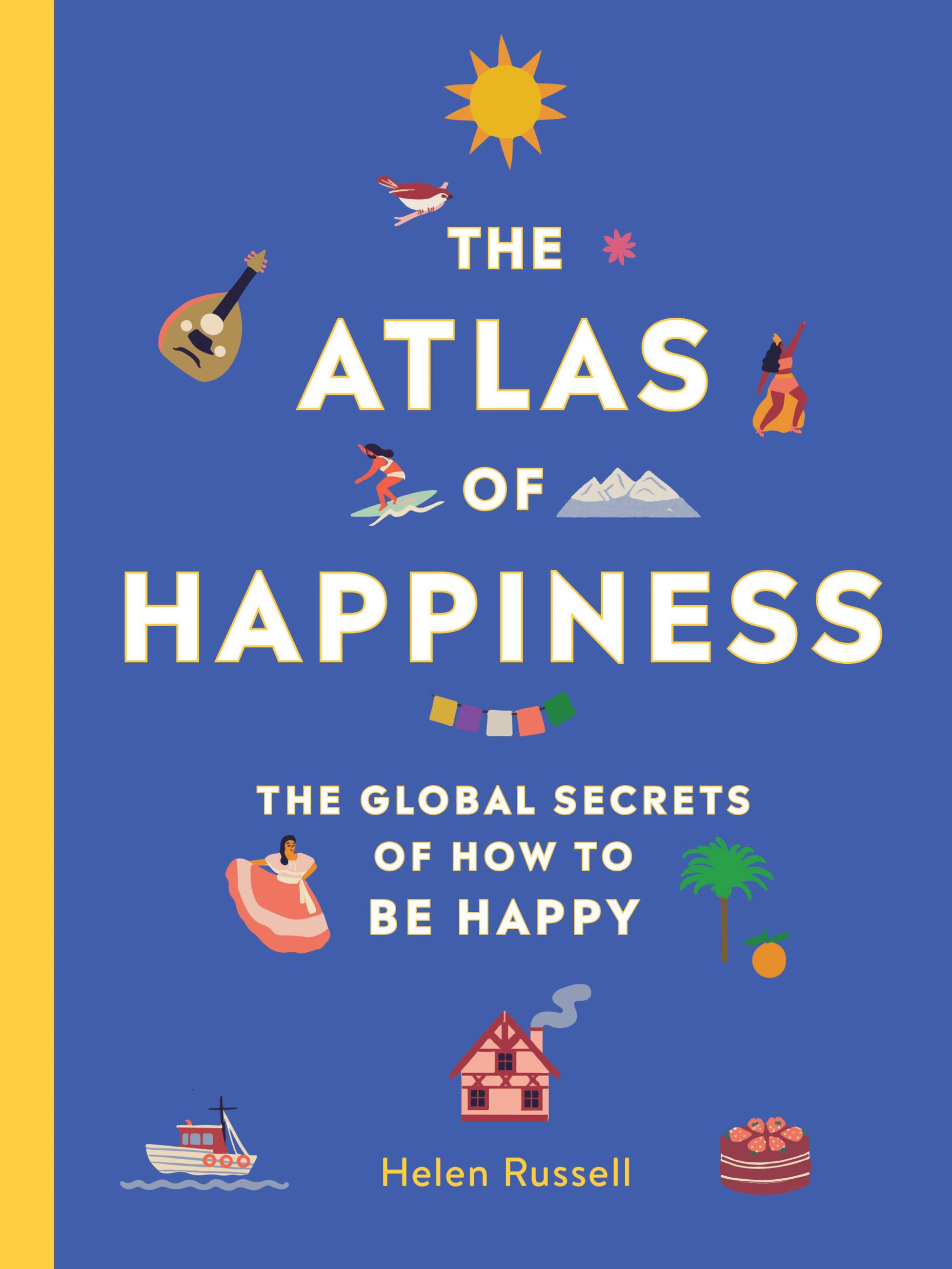

The Atlas of Happiness

The Global Secrets of How to Be Happy

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$12.99Price

$16.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $12.99 $16.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 7, 2019. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

A fun, illustrated guide that takes us around the world, discovering the secrets to happiness. Author Helen Russell (The Year of Living Danishly) uncovers the fascinating ways that different nations search for happiness in their lives, and what they can teach us about our own quest for meaning.

This charming and diverse assortment of advice, history, and philosophies includes:

- Sobremesa from Spain

- Turangawaewae from New Zealand

- Azart from Russia

- Tarab from Syria

- joie de vivre from Canada

- and many more.

Genre:

-

"This attractive, intriguing book-chock-full of colorful illustrations and breezy, informative essays-will be enjoyed by all, young or old."-BookPage

- On Sale

- May 7, 2019

- Page Count

- 288 pages

- Publisher

- Running Press

- ISBN-13

- 9780762467884

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use