Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

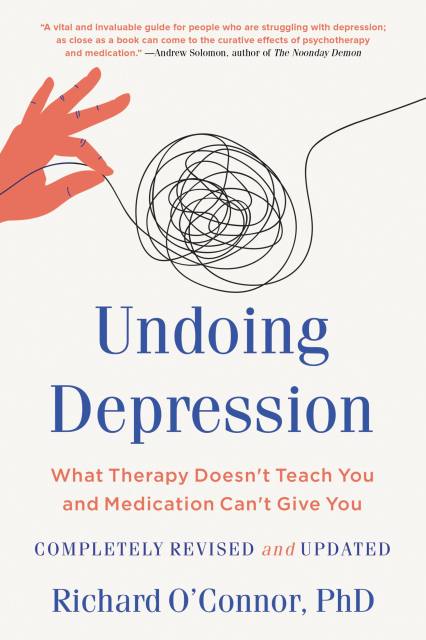

Undoing Depression

What Therapy Doesn't Teach You and Medication Can't Give You

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$21.99Price

$28.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback (Revised) $21.99 $28.99 CAD

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download $31.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 28, 2021. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Depression rates around the world have skyrocketed in the 20‑plus years since Richard O'Connor first published his classic book on living with and overcoming depression. Nearly 40 million American adults suffer from the condition, which affects nearly every aspect of life, from relationships, to job performance, physical health, productivity, and, of course, overall happiness. And in an increasingly stressful and overwhelming world, it's more important than ever to understand the causes and effects of depression, and what we can do to overcome it.

In this fully revised and updated edition — which includes updated information on the power of mindfulness, the relationship between depression and other diseases, the risks and side effects of medication, depression’s effect on thinking, and the benefits of exercise — Dr. O'Connor explains that, like heart disease and other physical conditions, depression is fueled by complex and interrelated factors: genetic, biochemical, environmental. But Dr. O'Connor focuses on an additional factor that is often overlooked: our own habits. Unwittingly we get good at depression. We learn how to hide it, and how to work around it. We may even achieve great things, but with constant struggle rather than satisfaction. Relying on these methods to make it through each day, we deprive ourselves of true recovery, of deep joy and healthy emotion.

Undoing Depression teaches us how to replace depressive patterns with a new and more effective set of skills. We already know how to "do" depression—and we can learn how to undo it. With a truly holistic approach that synthesizes the best of the many schools of thought about this painful disease, and a critical eye toward medications, O'Connor offers new hope—and new life—for sufferers of depression.

Genre:

-

"This is a vital and invaluable guide for people who are struggling with depression, as close as a book can come to the curative effects of psychotherapy and medication."Andrew Solomon, author of The Noonday Demon

-

"Undoing Depression is a book that anyone who has ever felt depressed, to any degree, can keep nearby as a useful companion. If you are really depressed, chain it to your clothing. Beautifully written, full of dependable and inspiring information, it offers countless creative things to do in the face of depression without trying to conquer it or win battles and wars. The intelligence in this book is deeply satisfying."Thomas Moore, author of Care of the Soul and Dark Nights of the Soul

-

"Essential reading for anyone who suffers from depression. The wisdom in these pages speaks directly to each individual, as if O'Connor knows exactly what we're going through. MDSG runs dozens of support groups each week and at our literature tables this is always the bestselling book. Packed with the latest research and fresh ideas, this new, updated edition hasn't lost the engaging style and compassion of the original."Howard Smith, Director of Operations, Mood Disorders Support Group

-

"This up-to-date, clearly written and illuminating book about the nature and treatment of depression is just plain wonderful. I view it as a gift to us all."Maggie Scarf, author of Unfinished Business, Intimate Partners, and Intimate Worlds

- On Sale

- Sep 28, 2021

- Page Count

- 400 pages

- Publisher

- Little Brown Spark

- ISBN-13

- 9780316261166

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use