Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

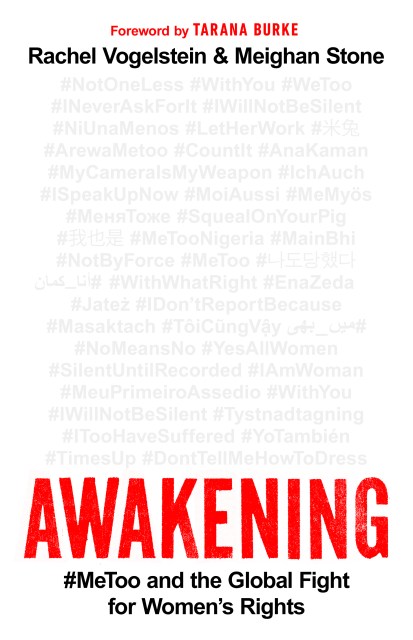

Awakening

#MeToo and the Global Fight for Women's Rights

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$16.99Price

$21.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $16.99 $21.99 CAD

- Hardcover $28.00 $35.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $24.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around July 13, 2021. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Foreword by Tarana Burke. Awakening chronicles the remarkable global impact of the #MeToo movement.

Since 2017, millions have joined the global movement known as #MeToo, catalyzing an unprecedented wave of women’s activism powered by technology that reaches across borders, races, religions, and economic divides. Today, women in more than 100 countries are using the hashtag to fight the violence and discrimination they face—and winning. What started as an online campaign against sexual harassment has triggered the most widespread cultural reckoning on women’s rights in history, with global implications for women’s participation in the economy, politics, and across social and cultural life.

Awakening is the first book to capture the global impact of this breakthrough movement. Bringing together political analysis and inspiring personal stories from women in seven countries—Brazil, China, Egypt, Nigeria, Pakistan, Sweden, and Tunisia—Awakening takes readers to the front lines of a networked movement that’s fundamentally shifting how women organize for their own equality.

Since 2017, millions have joined the global movement known as #MeToo, catalyzing an unprecedented wave of women’s activism powered by technology that reaches across borders, races, religions, and economic divides. Today, women in more than 100 countries are using the hashtag to fight the violence and discrimination they face—and winning. What started as an online campaign against sexual harassment has triggered the most widespread cultural reckoning on women’s rights in history, with global implications for women’s participation in the economy, politics, and across social and cultural life.

Awakening is the first book to capture the global impact of this breakthrough movement. Bringing together political analysis and inspiring personal stories from women in seven countries—Brazil, China, Egypt, Nigeria, Pakistan, Sweden, and Tunisia—Awakening takes readers to the front lines of a networked movement that’s fundamentally shifting how women organize for their own equality.

Genre:

-

"Awakening goes where no book has gone before, taking readers on a journey around the world in a powerful exploration of the most widespread cultural reckoning around women's rights in history. In chronicling the global impact of the #MeToo movement, Meighan Stone and Rachel Vogelstein capture the speed and scale of women-led organizing in the digital age, as well as the social, economic, and legal progress that's possible when we come together to demand change. Inspiring, insightful, and profoundly moving, this book is a must-read for women and men alike."Hillary Rodham Clinton

-

“Awakening champions the stories of women from Nigeria to Pakistan fighting for equality in schools, workplaces, courts, and government. Through their reporting and research, Meighan Stone and Rachel Vogelstein bring us closer to a new generation of women who are using digital activism to achieve change.”Malala Yousafzai, 2014 Nobel Peace Prize Laureate

-

“Dynamically told and sharply written, Awakening is the global #MeToo book we’ve been waiting for. This connective, powerful book widens the frame and pans away from the US, transporting readers over borders and across cultures so we can see what women fighting for freedom everywhere have long known: that stories are world-changing and sisterhood is powerful.”Jill Filipovic, journalist and author of OK Boomer, Let’s Talk, and The H-Spot

-

“Awakening is a must-read for anyone thinking about the social and political consequences of #MeToo. This book provides critical insight into the movement’s global impact and the future of equality for women around the world.”Soraya Chemaly, author of Rage Becomes Her: The Power of Women’s Anger

-

“An eye-opening global tour of women’s activism in the wake of the #MeToo movement. Spotlighting activists in seven countries, the authors make clear the diversity of the movement…Readers will be galvanized by these detailed portraits of bravery, creativity, and persistence in the struggle for women’s rights.”Publishers Weekly

-

“An inspiring overview of burgeoning women’s movements…A fresh perspective on continued challenges to women’s lives.”Kirkus Reviews

-

“This book isn't simply a history or a series of case studies and anecdotes; it compiles these narratives to show readers how change happens, so that we can continue to do the work of disrupting and dismantling systemic injustices….Complete with a broad selection of resources for advocacy, this call-to-action will spark the interest of aspiring activists."Library Journal

-

“Remarkable… What is clear, as Vogelstein and Stone so compellingly demonstrate, is the strength and sisterhood women have taken in each others’ struggles and each others’ victories. By retelling their stories and reinforcing the magnetism now binding these brave survivors across vastly different cultures and geographies, the authors have moved and mobilized their readers, giving us the chance to celebrate and learn from these strong women’s courage, tenacity, and power, and to carry forward the fight.”Philanthropy Women

- On Sale

- Jul 13, 2021

- Page Count

- 272 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781541758612

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use