Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

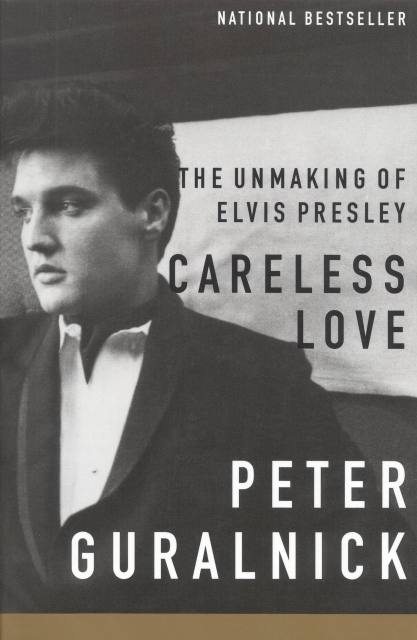

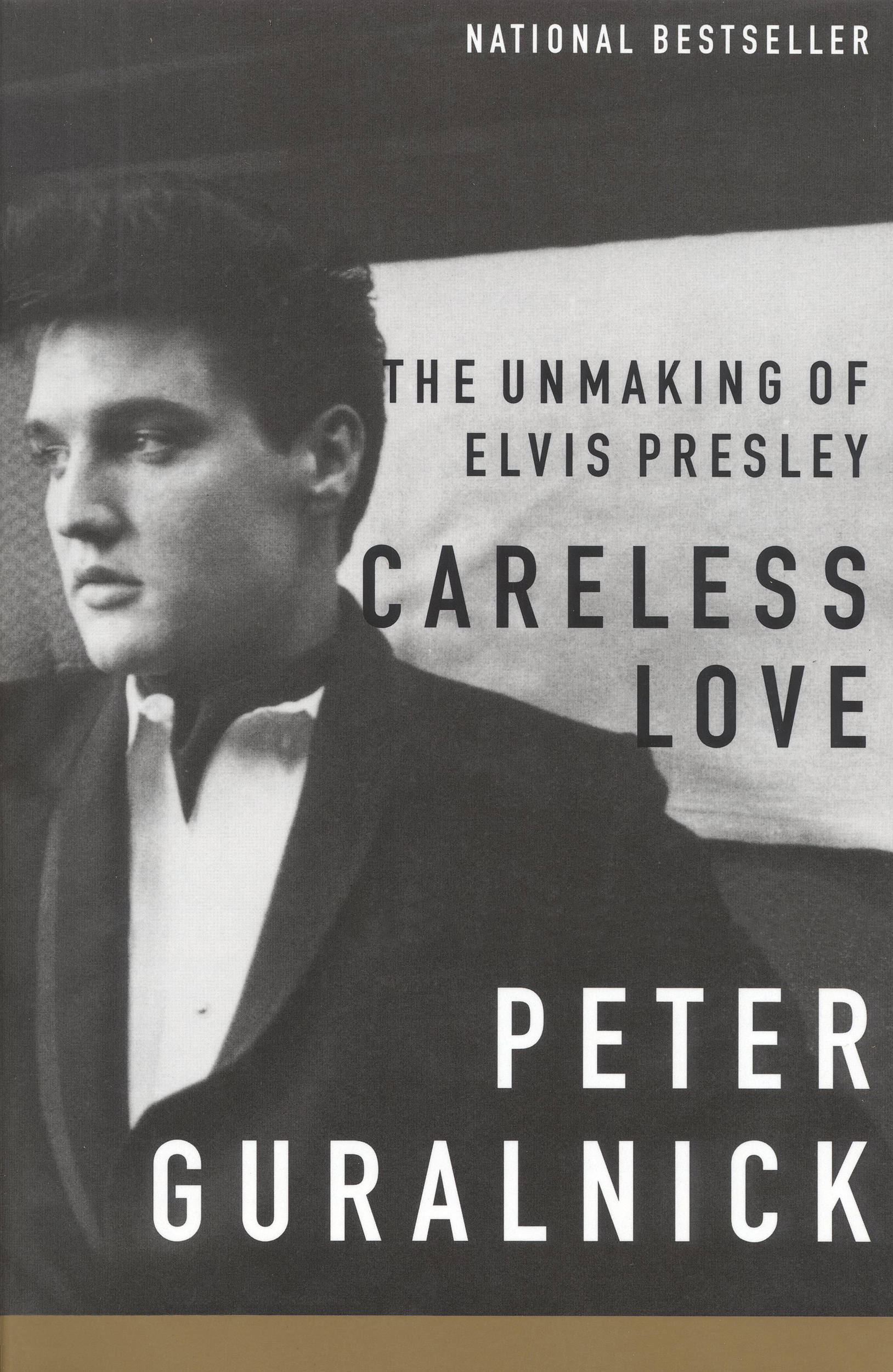

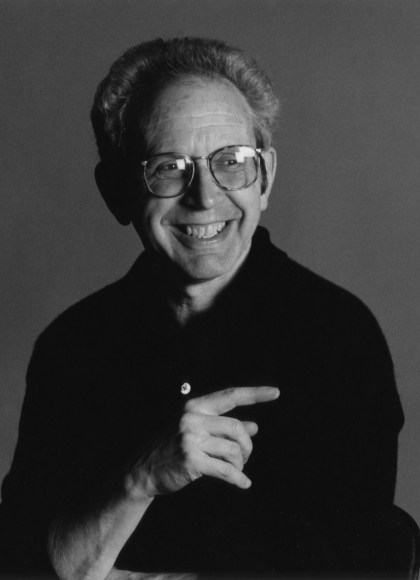

Careless Love

The Unmaking of Elvis Presley

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$11.99Price

$15.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Hardcover $40.00 $50.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback $24.99 $30.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around December 20, 2012. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Winner of the Ralph J. Gleason Music Book Award

Last Train to Memphis, the first part of Guralnick’s two-volume life of Elvis Presley, was acclaimed by the New York Times as “a triumph of biographical art.” This concluding volume recounts the second half of Elvis’ life in rich and previously unimagined detail, and confirms Guralnick’s status as one of the great biographers of our time.

Beginning with Presley’s army service in Germany in 1958 and ending with his death in Memphis in 1977, Careless Love chronicles the unravelling of the dream that once shone so brightly, homing in on the complex playing-out of Elvis’ relationship with his Machiavellian manager, Colonel Tom Parker. It’s a breathtaking revelatory drama that for the first time places the events of a too-often mistold tale in a fresh, believable, and understandable context.

Elvis’ changes during these years form a tragic mystery that Careless Love unlocks for the first time. This is the quintessential American story, encompassing elements of race, class, wealth, sex, music, religion, and personal transformation. Written with grace, sensitivity, and passion, Careless Love is a unique contribution to our understanding of American popular culture and the nature of success, giving us true insight at last into one of the most misunderstood public figures of our times.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Dec 20, 2012

- Page Count

- 768 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown and Company

- ISBN-13

- 9780316206723

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use