Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

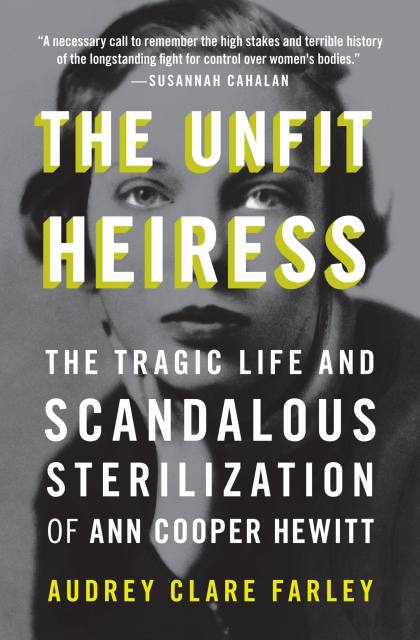

The Unfit Heiress

The Tragic Life and Scandalous Sterilization of Ann Cooper Hewitt

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$18.99Price

$23.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $18.99 $23.99 CAD

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Hardcover $28.00 $35.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $24.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 18, 2023. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

NAMED A BEST TRUE CRIME BOOK OF 2021 BY CRIMEREADS

For readers of The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks and The Phantom of Fifth Avenue, "a sensational story told with nuance and humanity" (Susannah Cahalan, #1 New York Times bestselling author) about the sordid court battle between Ann Cooper Hewitt and her socialite mother.

At the turn of the twentieth century, emboldened American women began to seek passion and livelihood outside the home. This alarmed authorities, who feared "over-sexed" women could destroy civilization, either by crossing the color line or passing their evident defects on to their children. Set against this backdrop, The Unfit Heiress chronicles the fight for inheritance between Ann Cooper Hewitt and her socialite mother Maryon, who had her daughter sterilized without her knowledge. A sensational court case ensued, and powerful eugenicists saw an opportunity to restrict reproductive rights in America for decades to come.

This riveting story unfolds through the brilliant research of Audrey Clare Farley, who captures the interior lives of these women on the pages and poses questions that remain relevant today: What does it mean to be "unfit" for motherhood? How do racial anxieties continue to influence who does and does not reproduce? In the battle for reproductive rights, can we forgive those who side against us? And can we forgive our mothers if they are the ones who inflict the deepest wounds?

Genre:

-

"A disturbing yet thought-provoking tale of family strife and ethically unsound medical practice."Kirkus Reviews

-

“THE UNFIT HEIRESS is a sensational story told with nuance and humanity with clear reverberations to the present. Historian Audrey Clare Farley's writing jumps off the page, as Ann Cooper Hewitt, once a one-dimensional tabloid fixation, is brought into full relief as a complicated victim of her time, standing in the crosshairs of the growing eugenics movement and the emergence of a "over-sexed" and "dangerous" New Woman. But most importantly, this book is a necessary call to remember the high stakes and terrible history of the longstanding fight for control over women's bodies.”Susannah Cahalan, #1 New York Times bestselling author of Brain on Fire

-

“THE UNFIT HEIRESS is the propulsive tale of a high-society scandal that triggered a high-stakes courtroom battle. It is also an illuminating exploration of America’s long, dark history of eugenics and forced sterilization. By braiding together these narrative threads, Audrey Clare Farley has accomplished the rare feat of writing a book that is as thought-provoking as it is page-turning.”Luke Dittrich, New York Times bestselling author Patient H.M.

-

“This book is as timely as ever. A gripping tale about the atrocity of systematic reproductive control.”Booklist, starred review

-

“Farley sets a brisk pace and persuasively reimagines the dynamic between Ann and Maryon. This is an eye-opening portrait of an obscure yet fascinating case.”Publishers Weekly

-

“Expertly blending biography and history, and using the life of Ann Cooper Hewitt as a backdrop, Farley has created an absorbing biography effectively explaining how the legacy of eugenics still persists today. Hewitt’s story will engage anyone interested in women’s history.”Library Journal

-

“THE UNFIT HEIRESS is not only a fascinating look at a wildly dysfunctional high society family, it’s also a compulsively readable account of the reproductive myths and bigotry-driven pseudoscience that still shape our world today.”Rachel Monroe, author of Savage Appetites

-

"THE UNFIT HEIRESS is a triumph of compassion, historical inquiry, and intellectual rigor. In her elegant telling of Ann Cooper Hewitt's story, Farley shines her bright, empathetic light on profoundly imperfect humans and the myriad, often tragic ways we grapple for fulfillment. At the same time, she renders with crystalline precision the history of American eugenics, insisting—gently, yet steadfastly—that we look where we'd rather avert our gaze. This book startled me, seized my attention, and summoned my empathy when I least expected it."Rachel Vorona Cote, author of Too Much

-

"In Audrey Clare Farley's book, the fascinating and unsettling case—and the worldwide media sensation it caused—is carefully revisited to expose what it meant to be considered an unfit parent and how easily family can become foes."Town and Country

-

“This well-researched and endlessly readable book is centered on the sterilization of Ann Cooper Hewitt, deemed too promiscuous by her mother to receive her father’s inheritance. Part biography and part history of eugenics, this one is intriguing and terrifying.”Ms. Magazine

-

“[Farley] keenly investigates the culture of eugenics that surrounded and pervaded both Ann’s life and court case...The most indicting feature of Farley’s book is not America’s eugenic past but America’s eugenic present.”Lady Science

-

“In her new book, The Unfit Heiress, Audrey Clare Farley untangles this dark and complex chapter of American history and shines a light on official and medical complicity in a horrifying system. Her book is exceedingly well-researched yet reads with the momentum of a thriller.”Crimereads

-

“The Unfit Heiress: The Tragic Life and Scandalous Sterilization of Ann Cooper Hewitt by Audrey Clare Farley, tells the sad and shocking tale of Cooper Hewitt, the daughter of famed engineer and inventor Peter Cooper Hewitt, and how her case reflected a time when eugenics was not only frighteningly common, but widely accepted in the US.”The New York Post

-

"[G]ripping, unsettling, reading."The Progressive

-

"Farley has presented an excellent case here. The book is fascinating on a variety of levels . . . not just a titillating story about greed, but one that delves further into the human mind and poor judgement, to say the least."New York Journal of Books

- On Sale

- Apr 18, 2023

- Page Count

- 320 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9781538753361

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use