Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

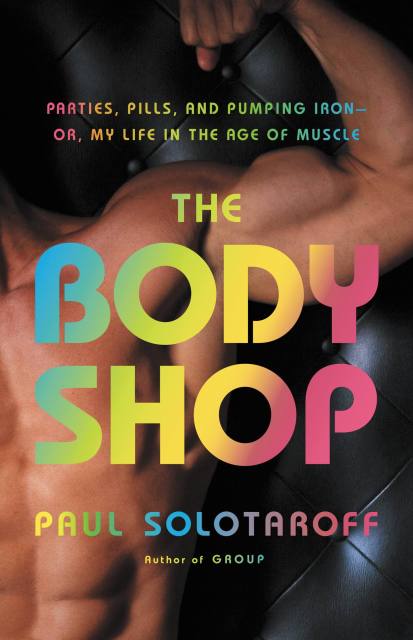

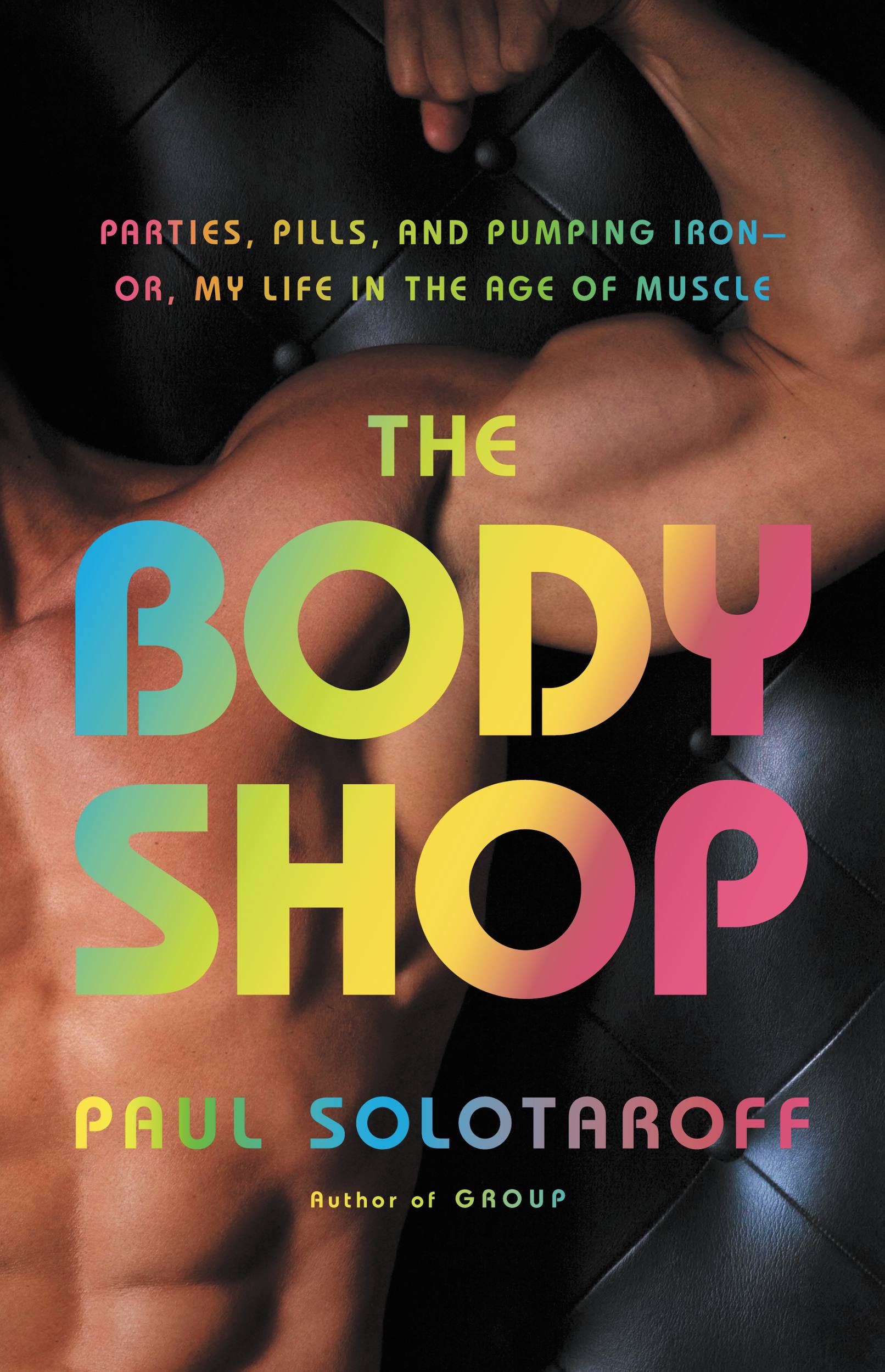

The Body Shop

Parties, Pills, and Pumping Iron -- Or, My Life in the Age of Muscle

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$13.99Price

$17.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $13.99 $17.99 CAD

- Hardcover $37.00 $47.00 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around July 26, 2010. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

In a matter of months, he grew from a dorky beanpole into a hulking behemoth, showing off his rock hard muscles first on the streets of New York City and then alongside his colorful gym-rat friends in strip clubs and in the homes of the gotham elite. It was a swinging time, when “Would you like to dance?” turned into “Your place or mine?” and the guys with the muscles had all the ladies — until their bodies, like Solotaroff”s, completely shut down.

But this isn’t the gloom-and-doom addiction one might expect — Solotaroff looks back at even his lowest points with a wicked sense of humor, and he sends up the disco era and its excess with all the kaleidoscopic detail of Boogie Nights or Saturday Night Fever.

Written with candor and sarcasm, The Body Shop is a memoir with all the elements of great fiction and dazzlingly displays Paul Solotaroff’s celebrated writing talent.

But this isn’t the gloom-and-doom addiction one might expect — Solotaroff looks back at even his lowest points with a wicked sense of humor, and he sends up the disco era and its excess with all the kaleidoscopic detail of Boogie Nights or Saturday Night Fever.

Written with candor and sarcasm, The Body Shop is a memoir with all the elements of great fiction and dazzlingly displays Paul Solotaroff’s celebrated writing talent.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Jul 26, 2010

- Page Count

- 304 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown and Company

- ISBN-13

- 9780316088831

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use