Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

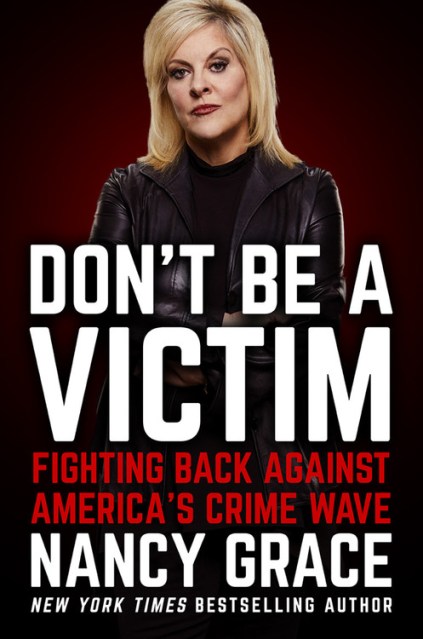

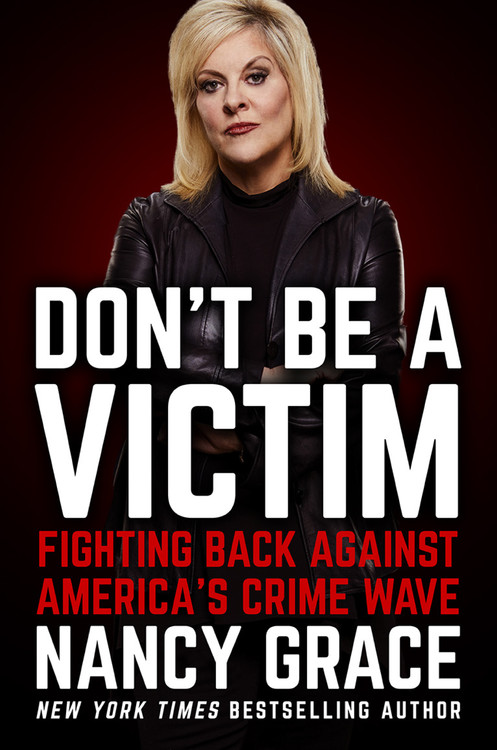

Don't Be a Victim

Fighting Back Against America's Crime Wave

Contributors

By Nancy Grace

With John Hassan

Formats and Prices

Price

$28.00Price

$35.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $28.00 $35.00 CAD

- ebook $15.99 $19.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback $18.99 $23.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 22, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Nancy Grace wasn’t always the iconic legal commentator we know today. One moment changed her entire future forever: her fiancé Keith was murdered just before their wedding. Driven to deliver justice for other crime victims, Nancy became a felony prosecutor and for a decade, put the “bad guys” behind bars in inner-city Atlanta.

Now, with a new and potentially life-saving book, Nancy puts her crime-fighting expertise to work to empower you stay safe in the face of daily dangers. Packed with practical advice and invaluable prevention tips, Don’t Be a Victim shows you how to:

- Fend off threats of assaults, car-jack and home invasion

- Defend yourself against online stalking, computer hackers and financial fraudsters

- Stay safe in your own home, at school and other public settings like parking garages, elevators and campsites

- Protect yourself while shopping, driving and even on vacation

With insights on so many potential threats, you’ll be empowered to protect yourself and your children at home and in the world at large by being proactive! Nancy’s crime-fighting expertise helps keep you, your family, and those you love out of harm’s way.

Genre:

-

"One of the greatest broadcasters of our time, Nancy Grace awakens us to the dark forces hiding among us."Dr. Mehmet Oz

-

"Nancy Grace has been America's preeminent crime victim advocate for as long as I have known her, and I have known her for more than 20-years. She understands the emotional and psychological suffering that crime victims endure, and always responds with empathy, compassion and dignity. Whether you are a victim of elder abuse, or a critically missing child, Nancy Grace will be your champion until justice is served."Marc Klaas, president of KlaasKids Foundation

-

"From her days at Court TV to her long-running show on CNN Headline News to her newest ventures, Injustice and Crime Stories, Nancy Grace has been one of America's foremost voices for victims. Her new book takes that advocacy to a newer, higher level. She provides a step-by-step and risk-by-risk guide for every parent, every child and every person on how to avoid becoming a victim."ErnieAllen, Chairman, WePROTECT Global Alliance

-

"[A] sensible guide on how to avoid becoming a crime victim...Grace's conversational tone makes for easy reading. Those concerned with personal safety will find comfort and practical advice."Publishers Weekly

- On Sale

- Sep 22, 2020

- Page Count

- 384 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9781538732298

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use