Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

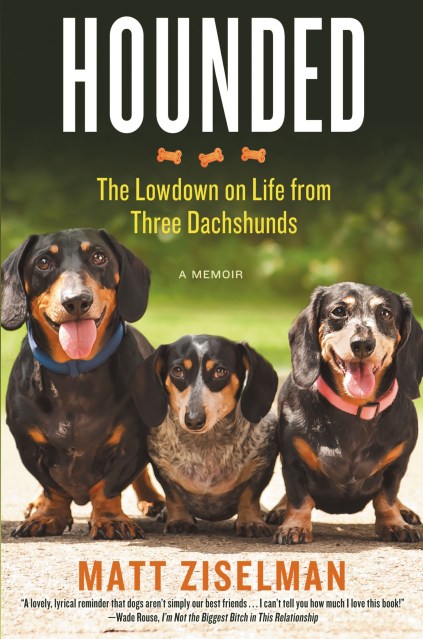

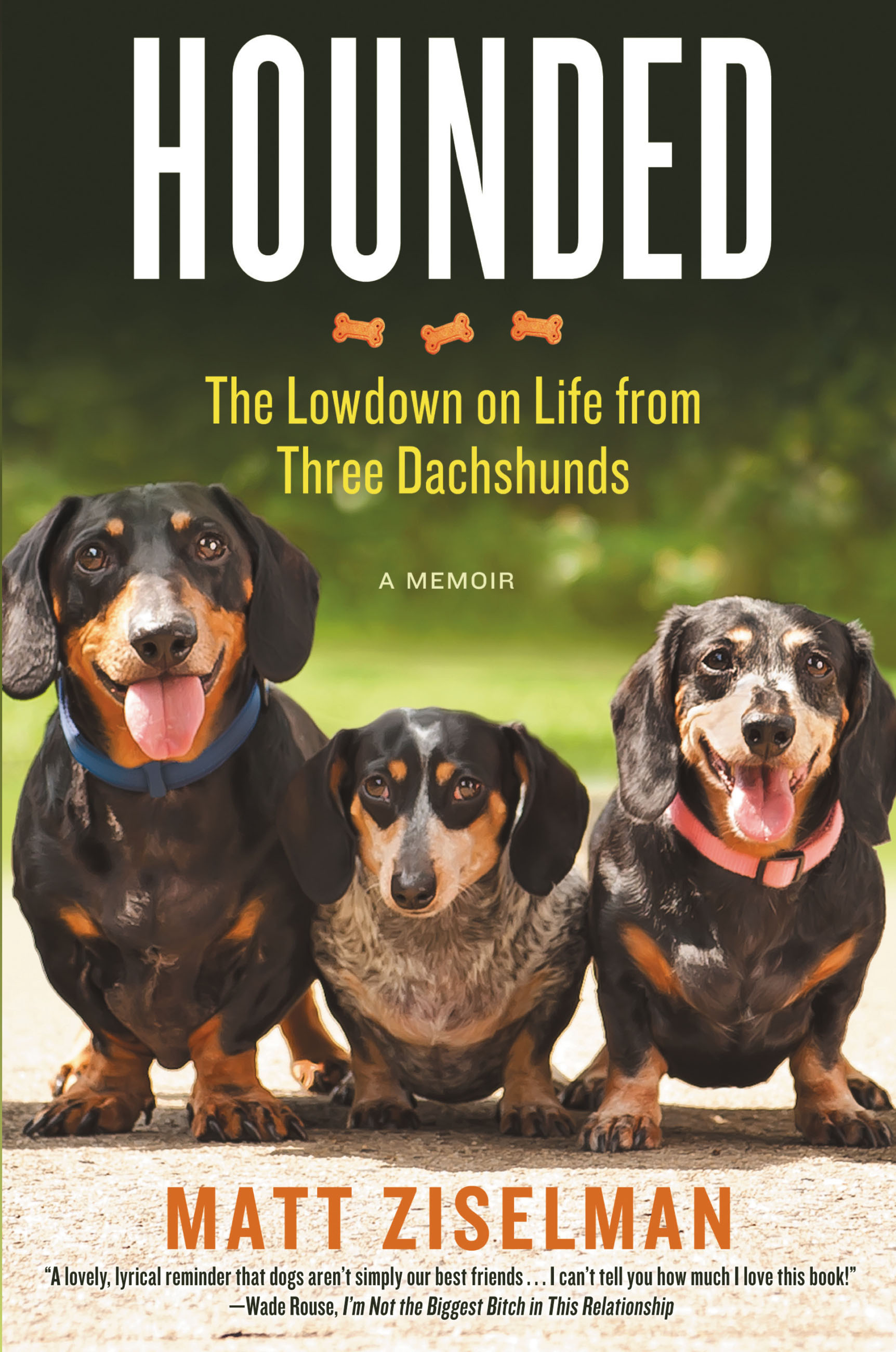

Hounded

The Lowdown on Life from Three Dachshunds

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$7.99Price

$9.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $7.99 $9.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback $15.00 $17.00 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 14, 2013. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Armed with a fresh, creative voice that is unabashedly cranky one moment and profoundly poignant the next, Ziselman mixes hilarious canine stories, with heartfelt reminiscences from his own life, the results of which is a memoir of illuminating life lessons, courtesy of the three thoroughly Teutonic Dachshunds that he shares his life (and couch) with: Baxter, Maya and Molly. Seemingly mundane moments, like Baxter’s incessant, neuroses inducing staring, Maya’s inexplicable refusal to walk through the front door and Molly’s obsessive compulsive love for a torn and tattered blanket become, through Ziselman’s insightful eyes, a treasure trove of observations that any dog-lover will appreciate. In a market where Americans spend more than $40 billion a year on their pets, this work of razor-sharp wit and quiet tenderness will reach out and grab readers everywhere by the heartstrings and-quite possibly-their leashes.

HOUNDED wraps universal insights in hot-dog-shaped packages, providing true dog lovers with many knowing nods, honest belly laughs and an accurate, warts-and-all reflection of the fascination, wonder and love that they have for their dogs.

And that Matt Ziselman obviously has for his.

Genre:

- On Sale

- May 14, 2013

- Page Count

- 288 pages

- Publisher

- Center Street

- ISBN-13

- 9781455527007

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use