By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

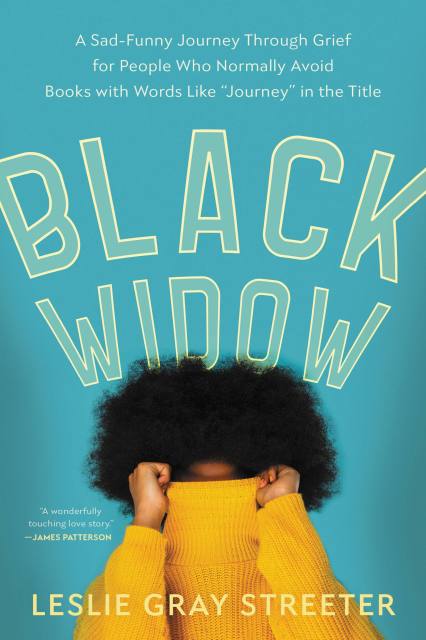

Black Widow

A Sad-Funny Journey Through Grief for People Who Normally Avoid Books with Words Like "Journey" in the Title

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Mar 10, 2020

- Page Count

- 272 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown and Company

- ISBN-13

- 9780316490726

Price

$11.99Price

$15.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback $16.99 $22.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 10, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Leslie Gray Streeter is not cut out for widowhood. She's not ready for hushed rooms and pitying looks. She is not ready to stand graveside, dabbing her eyes in a classy black hat. If she had her way she'd wear her favorite curve-hugging leopard print dress to Scott's funeral; he loved her in that dress! But, here she is, having lost her soulmate to a sudden heart attack, totally unsure of how to navigate her new widow lifestyle. ("New widow lifestyle." Sounds like something you'd find products for on daytime TV, like comfy track suits and compression socks. Wait, is a widow even allowed to make jokes?)

Looking at widowhood through the prism of race, mixed marriage, and aging, Black Widow redefines the stages of grief, from coffin shopping to day-drinking, to being a grown-ass woman crying for your mommy, to breaking up and making up with God, to facing the fact that life goes on even after the death of the person you were supposed to live it with. While she stumbles toward an uncertain future as a single mother raising a baby with her own widowed mother (plot twist!), Leslie looks back on her love story with Scott, recounting their journey through racism, religious differences, and persistent confusion about what kugel is. Will she find the strength to finish the most important thing that she and Scott started?

Tender, true, and endearingly hilarious, Black Widow is a story about the power of love, and how the only guide book for recovery is the one you write yourself.

-

One of Glamour’s Best Books of 2020

-

"Tender, clever, and endearing, this story of love and loss will have you alternating between laughter and tears. Leslie's mix of break-it-down humor and heartbreaking truth make this book playful and deep in all the right places."Tembi Locke, New York Timesbestselling author of From Scratch

-

"So often, readers feel it's not okay to laugh in times of grief, but Streeter not only reminds us its okay, she encourages it. Black Widow has earned a place on the shelf next to Joan Didion and Cheryl Strayed in the realm of the grief memoir."Booklist

-

"Black Widow is a beautiful love story that also happens to be a grief story. Leslie Gray Streeter tells the whole tale-falling in love, marriage, adopting, parenthood, death, moving on-with her captivating wit. Only she could make Black Widow so deeply moving, painfully funny, altogether unforgettable."Rob Sheffield, author of Dreaming the Beatles and Love is a Mix Tape

-

"Black Widow is a very special one of a kind book, a wonderfully touching love story that will make you laugh and cry, sometimes on the same page. Even more outstanding is Leslie Gray Streeter's voice. You won't soon forget Black Widow."James Patterson

-

"Grief is a heavy darkness with spots of unexpected, unpredictable light. Leslie's book is a light for those still stuck in the dark--a sad, funny, personal story filled with universal truths about life and love and loss."Nora McInerny, author of The Hot Young Widows Club and No Happy Endings

-

"I can only marvel at Leslie Streeter's resilience, humor, and candor. Black Widow is a funny, heartwarming read about one of the worst things that can happen to a person. We should all be this grounded in our day-to-day lives."Laura Lippman, NewYork Times bestselling author of Ladyin the Lake

-

"When Streeter's husband died, leaving her to raise their baby with her mother, also a widow, the journalist and playwright was plunged into a new, surprisingly funny life of coffin shopping and staring down racism."Glamour

-

"This hopeful account will appeal to readers who enjoy stories of resiliency and new life chapters."Publishers Weekly

-

A laugh-out-loud book for women who aren't ready to navigate widowhood in the traditional way.New York Post

-

"This is a great read for anyone who's suffered loss of a loved one. I'd say it's chicken soup for any soul in grief. Anyone who reads this will undoubtedly feel consoled."Aphrodite Jones

-

"I can't recommend this book enough. It made me realize how much I love my family and that LOVE conquers all."Johnathon Schaech

-

"In her seriocomic debut, Palm Beach Post entertainment columnist Streeter pays tribute to her husband, Scott, by sharing detailed stories about their life together and her many struggles dealing with his death...Streeter's candid exploration will resonate with those who have dealt with similar circumstances. A love-filled eulogy to a beloved husband and the special times the couple shared before he died."Kirkus

-

"If this book title isn't already a knockout to you, then I don't know what to say. But in all seriousness, humor is necessary to survive grief, and Leslie Gray Streeter imbues her memoir of losing her husband with just that. A love story that contemplates death, race, and single motherhood, Streeter's book is not something to gloss over."San Francisco Weekly

-

"Using humor and a powerful narrative, Streeter guides us into an unexpected life of widowhood, single motherhood, and newfound wisdom."Palm Beach Daily News

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use