Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

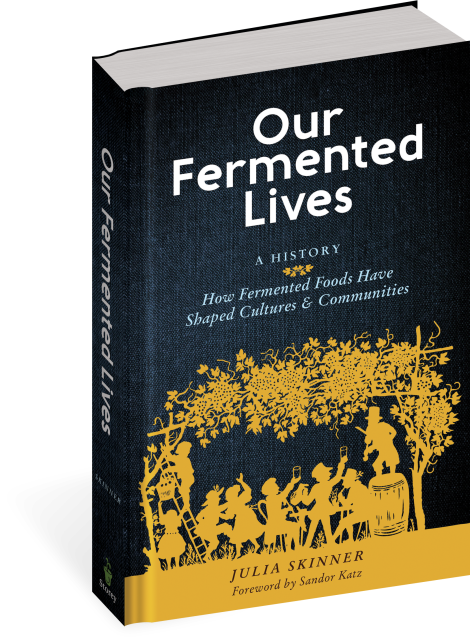

Our Fermented Lives

A History of How Fermented Foods Have Shaped Cultures & Communities

Contributors

Foreword by Sandor Ellix Katz

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Sep 27, 2022

- Page Count

- 384 pages

- Publisher

- Storey

- ISBN-13

- 9781635863833

Price

$30.00Price

$38.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $30.00 $38.00 CAD

- ebook $14.99 $18.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 27, 2022. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

-

"Skinner pours forth so much historical and practical information about fermentation that her book is indispensable for all levels of readers intrigued by this ancient process." - Booklist"Julia Skinner has given us a necessary and user friendly field guide to the bacteria that give zest and tang to the ecology of our plates and pantries. This is an exciting addition to the body of home knowledge about our friend fermentation and how to wield its magic.” - Michael W. Twitty, author of The Cooking Gene

"This profound and important text on the intersection of culture and fermentation offers not only history, but also guidelines on fermentation and recipes as well. How better to understand a culture or a time period than to understand and prepare its food?" - Manhattan Book Review

“Julia has a seamless way of weaving history, recipes, tales together making one feel as if they are being transported to another place in time through smells, facts flavors. Her deep knowledge, and reverence for the craft of preserving food makes my life as a forever student all the more joyful.” - Cortney Burns, Chef Author of Nourish Me Home“Skinner illuminates the deep past through recipes and stories that tether the foods of today to those of our ancestors. In doing so, she paints an expansive picture of just how intractably linked fermentation is to the human endeavor." - David Zilber, The Noma Guide to Fermentation "Interesting, eloquent – a sensual journey of discovery and exploration that transcends the very fabric of space and time. From ancient Jiahu in China to the heart of the Brazilian rainforest, these stories will captivate you. " - Jeremy Umansky, Koji Alchemy

“A necessary book. Skinner has brilliantly combined practical, hands-on knowledge with historical context and anthropological themes for this treasure trove!” - Jenny Dorsey, chef, writer, and founder of Studio ATAO “The recipes are fabulous, and by setting microbes in their historical and social contexts, Skinner makes this book a unique addition to the literature on fermentation.” - Ken Albala, professor of history, University of the Pacific “Skinner weaves together ancient history with modern conversations about food security, inequality, and appropriation. In doing so, she has created a rich tapestry that illuminates fermentation’s place in the human experience — one that encompasses food preservation, flavor, health, and the intersection of human and microbial cultures.” — Kirsten K. Shockey, author of Fermented Vegetables and cofounder of The Fermentation School