Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

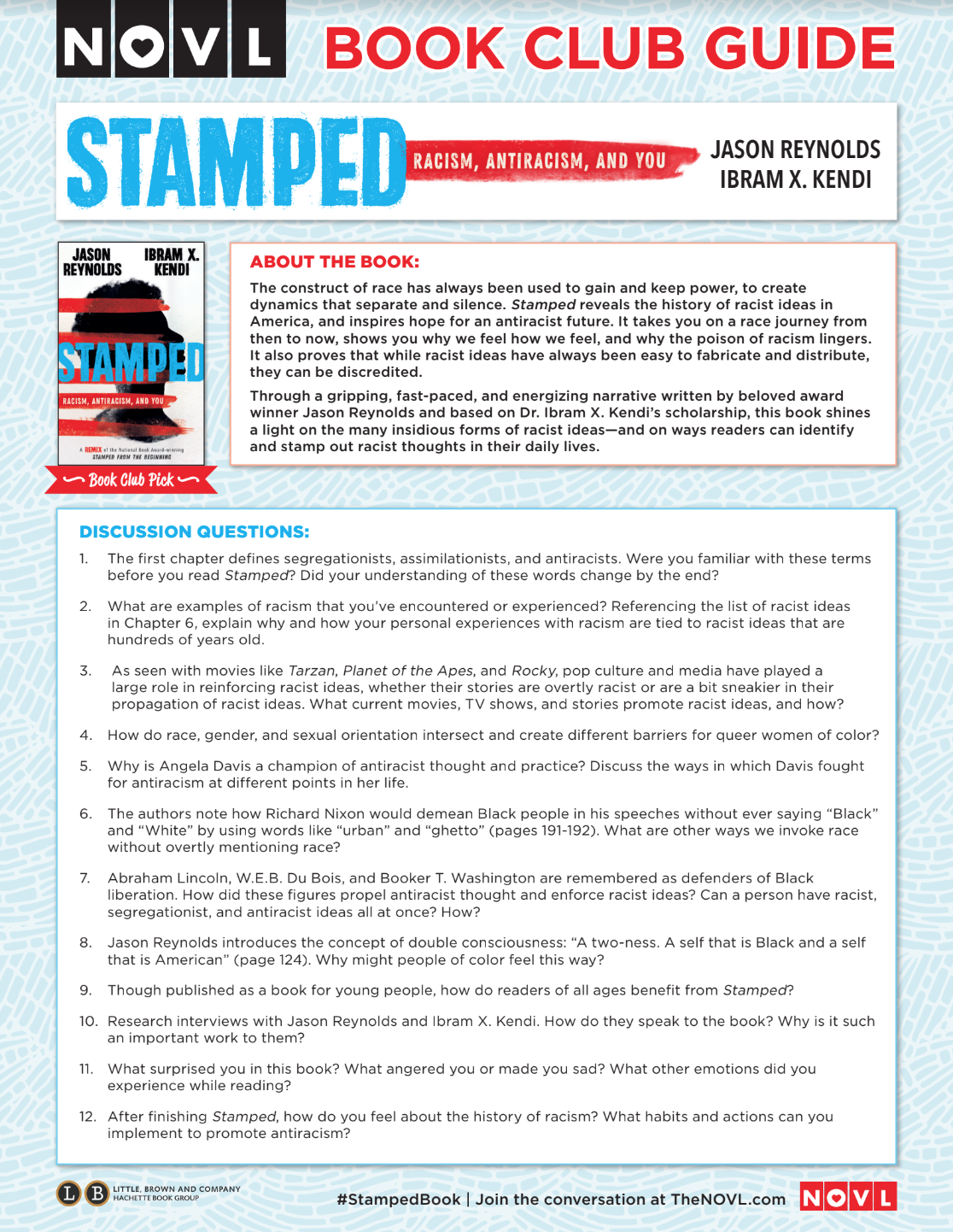

Stamped: Racism, Antiracism, and You

A Remix of the National Book Award-winning Stamped from the Beginning

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$10.99Price

$13.99 CADFormat

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 10, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

This crucial, empowering, #1 New York Times bestselling exploration of racism—and antiracism—in America makes critical ideas accessible for teen readers, adapted from Ibram X. Kendi's National Book Award-winning Stamped from the Beginning.

This is NOT a history book.

This is a book about the here and now. This is NOT a history book.

A book to help us better understand why we are where we are.

A book about race.

The construct of race has always been used to gain and keep power, to create dynamics that separate and silence. Racist ideas are woven into the fabric of this country, and the first step to building an antiracist America is acknowledging America's racist past and present. This book takes you on that journey, showing how racist ideas started and were spread, and how they can be discredited.

Through a gripping, fast-paced, and energizing narrative written by beloved award-winner Jason Reynolds with research from renowned author Ibram X. Kendi, Stamped shines a light on the many insidious forms of racist ideas—and on ways you can identify and stamp out racist thoughts, leading to a better future.

Download the free educator guide here: https://www.hachettebookgroup.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Stamped-Educator-Guide.pdf

Now available for younger readers: Stamped (for Kids): Racism, Antiracism, and You

Now available for younger readers: Stamped (for Kids): Racism, Antiracism, and You

Genre:

-

Praise for Stamped: Racism, Antiracism, and You:Jacqueline Woodson, bestselling and National Book Award-winning author of Brown Girl Dreaming

#1 New York Times bestseller

#1 IndieBound bestseller

USAToday bestseller

Wall Street Journal bestseller

2020 Kirkus Prize finalist

Best Teen Book of the Year, Kids’ Book Choice Awards Winner

A TIME Magazine Ten Best Children’s and YA Books of the Year

A Parents Magazine best book of the year

A Washington Post Best Children's Book of the Year

A Publishers Weekly best book of the year

An SLJ best book of the year

A 2020 New York Public Library Best Teen Book

A 2020 Chicago Public Library Best of the Best Teen Book

"An amazingly timely and stunningly accessible manifesto for young people....At times funny, at times somber but always packed with relevant information that is at once thoughtful and spot-on, Stamped is the book I wish I had as a young person and am so grateful my own children have now." -

"Sheer brilliance....An empowering, transformative read. Bravo."Jewell Parker Rhodes, New York Times bestselling author of Ghost Boys

-

"Teens are often searching for their place in the world, in Stamped, Reynolds gives context to where we are, how we got here, and reminds young people-and all of us-that we have a choice to make about who we want to be. This unapologetic telling of the history of racism in our nation is refreshingly simple and deeply profound. This is the history book I needed as a teen."Renée Watson, New York Timesbestselling and Newbery Honor-winning author of Piecing Me Together

-

"Jason Reynolds has the amazing ability to make words jump off the page. Told with passion, precision, and even humor, Stamped is a true story-a living story-that everyone needs to know."Steve Sheinkin, New York Times bestselling and award-winning author of Bomb and Born to Fly

-

"The R-word: Racism. Some tuck tail and run from it. Others say it's no longer a thing. But Dr. Kendi breaks it down, and Jason Reynolds makes it easy to understand. Mark my words: This book will change everything."Nic Stone, bestselling author of Dear Martin

-

"If knowledge is power, this book will make you more powerful than you've ever been before."Ibi Zoboi, author of the National Book Award finalist American Street

-

"Reading this compelling not-a-history book is like finding a field guide to American racism, allowing you to quickly identify racist ideas when you encounter them in the wild."Dashka Slater, author of The 57 Bus

-

"Reynolds's engaging, clear prose shines a light on difficult and confusing subjects....This is no easy feat."The New York Times Book Review

-

"the must-read book of the moment...potent and provocative"--San Francisco Chronicle

-

* "Readers who want to truly understand how deeply embedded racism is in the very fabric of the U.S., its history, and its systems will come away educated and enlightened. Worthy of inclusion in every home and in curricula and libraries everywhere. Impressive and much needed."Kirkus Reviews, starred review

-

* "An epic feat... More than merely a young reader's adaptation of Kendi's landmark work, Stamped does a remarkable job of tying together disparate threads while briskly moving through its historical narrative."Bookpage, starred review

-

* "Required reading for everyone, especially those invested in the future of young people in America."Booklist, starred review

-

* "Reynolds and Kendi eloquently challenge the common narrative attached to U.S. history. This adaptation, like the 2016 adult title, will undoubtedly leave a lasting impact. Highly recommended for libraries serving middle and high school students."School Library Journal, starred review

-

* "Eye-opening...this engaging overview offers readers lots to think about and should spark important conversations about this timely topic."School Library Connection, starred review

-

* "Reynolds (Look Both Ways) lends his signature flair to remixing Kendi's award-winning Stamped from the Beginning...Told impressively economically, loaded with historical details that connect clearly to current experiences, and bolstered with suggested reading and listening selected specifically for young readers, Kendi and Reynolds's volume is essential, meaningfully accessible reading."Publishers Weekly, starred review

-

“Thorough and educational…fresh and conversational...”TIME Magazine

-

“A must-read for everyone…eye-opening.”Seventeen Magazine

- On Sale

- Mar 10, 2020

- Page Count

- 320 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown Books for Young Readers

- ISBN-13

- 9780316453707

Read an Excerpt

Book Club & Educator Guides

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use