Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

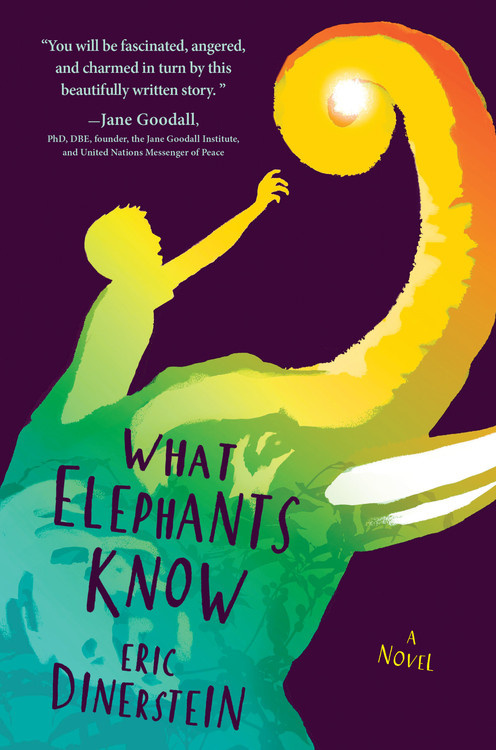

What Elephants Know

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$15.99Price

$20.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $15.99 $20.99 CAD

- ebook $7.99 $9.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 16, 2017. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

When the king’s government threatens to close the stable, Nandu, now twelve, searches for a way to save his family and community. A risky plan could be the answer. But to succeed, they’ll need a great tusker. The future is in Nandu’s hands as he sets out to find a bull elephant and bring him back to the Borderlands.

In simple poetic prose, author Eric Dinerstein brings to life Nepal’s breathtaking jungle wildlife and rural culture, as seen through the eyes of a young outcast, struggling to find his place in the world.

Genre:

- On Sale

- May 16, 2017

- Page Count

- 288 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown Books for Young Readers

- ISBN-13

- 9781484746479

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use