Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

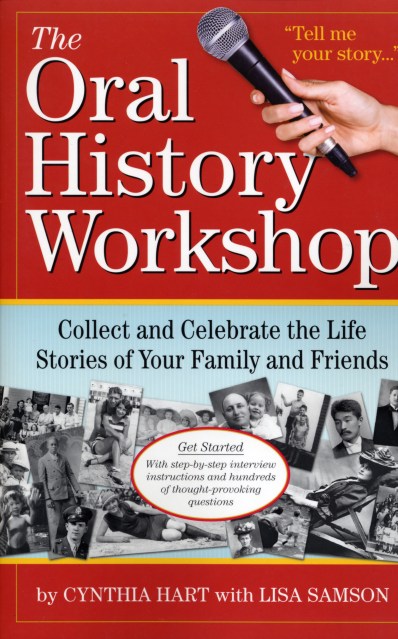

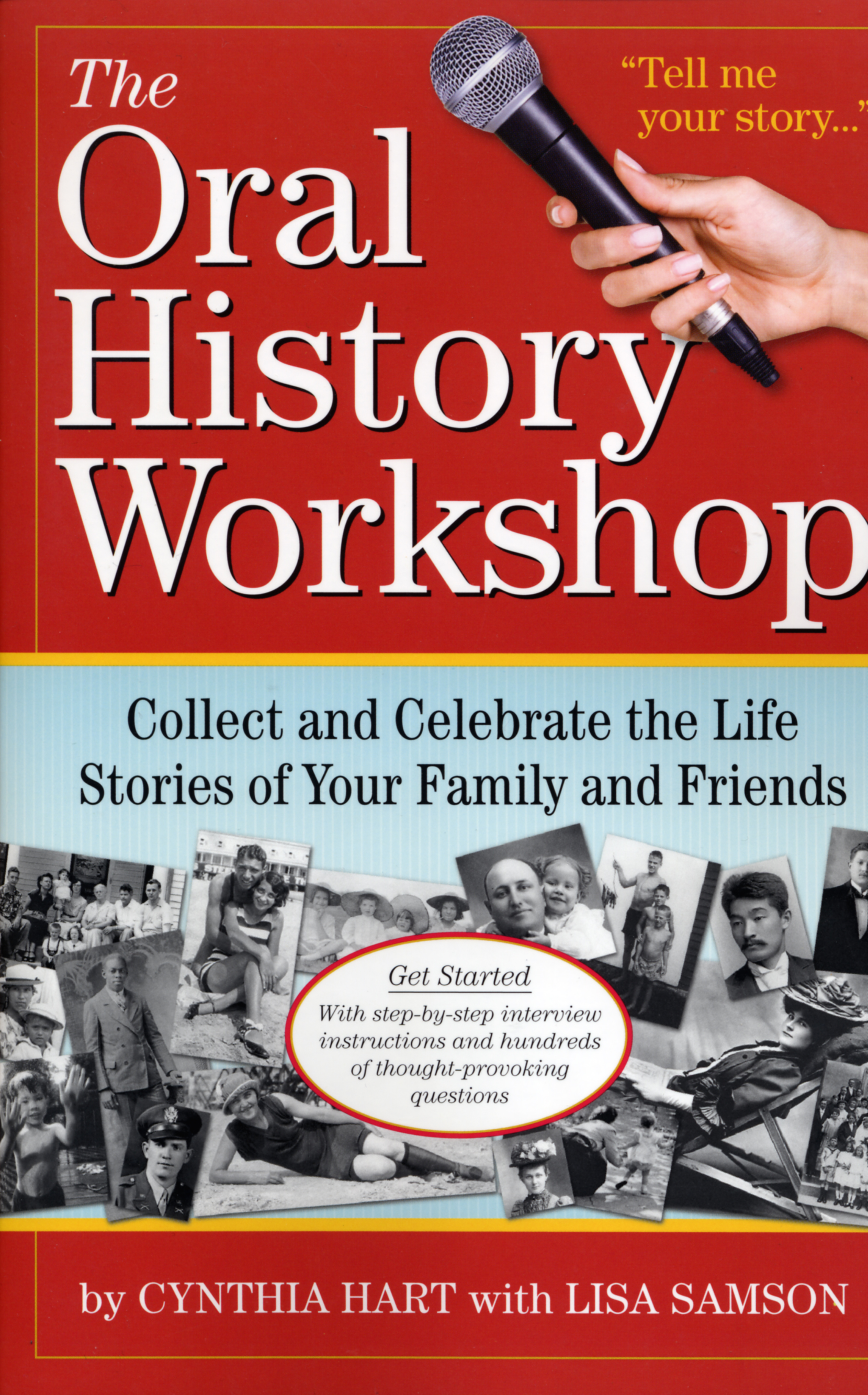

The Oral History Workshop

Collect and Celebrate the Life Stories of Your Family and Friends

Contributors

By Cynthia Hart

By Lisa Samson

Formats and Prices

Price

$9.99Price

$12.99 CADFormat

Format:

ebook $9.99 $12.99 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around August 28, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

We all know that we should ask now, before it’s too late, before the stories are gone forever. But knowing and doing are two different things.

Cynthia Hart, author of Cynthia Hart’s Scrapbook Workshop, shows exactly how to collect, record, share, and preserve a family member’s or a friend’s oral history in this practical and inspirational guide. The Oral History Workshop breaks down what too often feels like an overwhelming project into a series of easily manageable steps: how to prepare for an interview; how to become a better listener; why there’s always more beneath the surface and the questions to ask to get there; the pros and cons of video recording, including how your subjects should dress so the focus is on their words; four steps to keeping the interview on track; how to be attentive to your subject’s energy levels; and the art of archiving or scrapbooking the interview into a finished keepsake.

At the heart of the book are hundreds of questions designed to cover every aspect of your subject’s history: Do you remember when and how you learned to read? Who in your life showed you the most kindness? What insights have you gained about your parents over the years? Would you describe yourself as an optimist or a pessimist? In what ways were you introduced to music? What is the first gift you remember giving? If you could hold on to one memory forever, what would it be? When the answers are pieced together, a mosaic appears—a living history.

Cynthia Hart, author of Cynthia Hart’s Scrapbook Workshop, shows exactly how to collect, record, share, and preserve a family member’s or a friend’s oral history in this practical and inspirational guide. The Oral History Workshop breaks down what too often feels like an overwhelming project into a series of easily manageable steps: how to prepare for an interview; how to become a better listener; why there’s always more beneath the surface and the questions to ask to get there; the pros and cons of video recording, including how your subjects should dress so the focus is on their words; four steps to keeping the interview on track; how to be attentive to your subject’s energy levels; and the art of archiving or scrapbooking the interview into a finished keepsake.

At the heart of the book are hundreds of questions designed to cover every aspect of your subject’s history: Do you remember when and how you learned to read? Who in your life showed you the most kindness? What insights have you gained about your parents over the years? Would you describe yourself as an optimist or a pessimist? In what ways were you introduced to music? What is the first gift you remember giving? If you could hold on to one memory forever, what would it be? When the answers are pieced together, a mosaic appears—a living history.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Aug 28, 2018

- Page Count

- 180 pages

- Publisher

- Workman Publishing Company

- ISBN-13

- 9781523507184

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use