Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

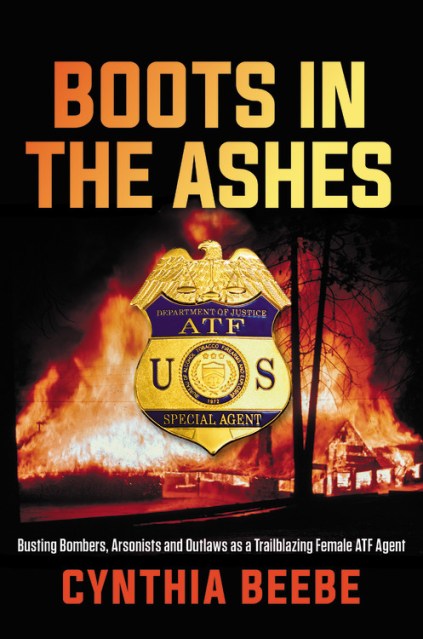

Boots in the Ashes

Busting Bombers, Arsonists and Outlaws as a Trailblazing Female ATF Agent

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$28.00Price

$35.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $28.00 $35.00 CAD

- ebook $14.99 $18.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around February 25, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

The thrilling career of ATF agent Cynthia Beebe is told through the lens of six-high profile cases involving bombings, arson, and the Hell’s Angels.

Boots in the Ashes is the memoir of Cynthia Beebe’s groundbreaking career as one of the first women special agents for the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives, (ATF). A smart and independent girl growing up in suburban Chicago, she unexpectedly became one of the first women to hunt down violent criminals for the federal government.

As a special agent for 27 years, Beebe gives the reader first-hand knowledge of the human capacity for evil. She tells the story of how, as a young woman, she overcame many obstacles on her journey through the treacherous world of illegal guns, gangs, and bombs. She battled conflicts both on the streets and within ATF. But Beebe learned how to thrive in the ultra-masculine world of violent crime and those whose job it is to stop it.

Beebe tells her story through the lens of six major cases that read like crime fiction: four bombings, one arson fire and a massive roundup of the Hell’s Angels on the West Coast. She also shares riveting never before revealed trial testimonies, including killers, bombers, arsonists, victims, witnesses and judges.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Feb 25, 2020

- Page Count

- 304 pages

- Publisher

- Center Street

- ISBN-13

- 9781546084594

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use