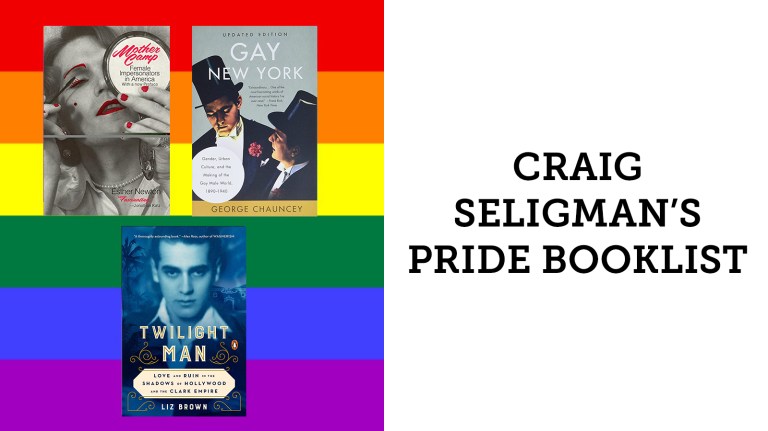

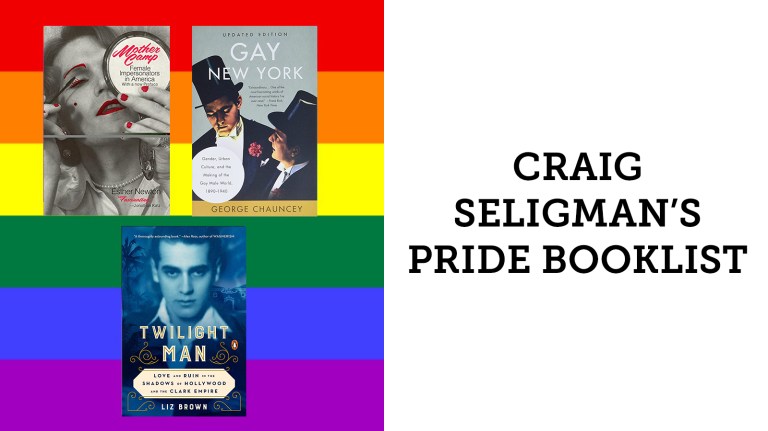

Craig Seligman's Pride Month Booklist

You’ve watched the video, now learn more about the books and pick up a copy.

Read full article

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

Doris Fish and the Rise of Drag

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around February 28, 2023. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use