Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

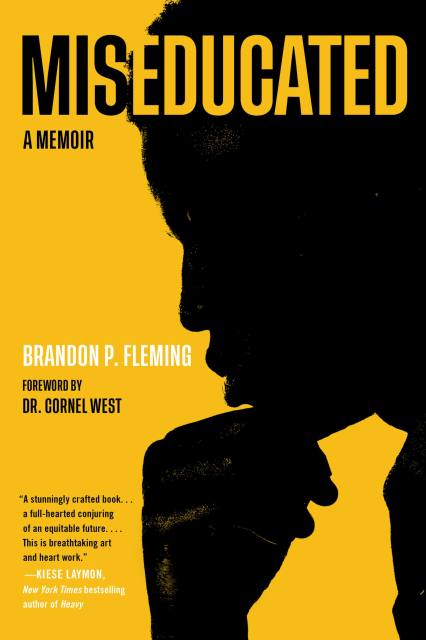

Miseducated

A Memoir

Contributors

Foreword by Cornel West

Formats and Prices

Price

$18.99Price

$24.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $18.99 $24.99 CAD

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Hardcover $28.00 $35.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $27.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around June 14, 2022. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

An inspiring memoir of one man’s transformation from a delinquent, drug-dealing dropout to an award-winning Harvard educator through literature and debate—all by the age of twenty-seven.

Brandon P. Fleming grew up in an abusive home and was shuffled through school, his passing grades a nod to his skill on the basketball court, not his presence in the classroom. He turned to the streets and drug deals by fourteen, saved only by the dream of basketball stardom.

When he suffered a career-ending injury during his first semester at a Division I school, he dropped out of college, toiling on an assembly line, until depression drove him to the edge. Miraculously, his life was spared.

Returning to college, Fleming was determined to reinvent himself as a scholar—to replace illiteracy with mastery over language, to go from being ignored and unseen to commanding attention. He immersed himself in the work of Black thinkers from the Harlem Renaissance to present day. Crucially, he found debate, which became the means by which he transformed his life and the tool he would use to transform the lives of others—teaching underserved kids to be intrusive in places that are not inclusive, eventually at Harvard University, where he would make champions and history.

Through his personal narrative, readers witness Fleming’s transformation, self-education, and how he takes what he learns about words and power to help others like himself. Miseducated is an honest memoir about resilience, visibility, role models, and overcoming all expectations.

Brandon P. Fleming grew up in an abusive home and was shuffled through school, his passing grades a nod to his skill on the basketball court, not his presence in the classroom. He turned to the streets and drug deals by fourteen, saved only by the dream of basketball stardom.

When he suffered a career-ending injury during his first semester at a Division I school, he dropped out of college, toiling on an assembly line, until depression drove him to the edge. Miraculously, his life was spared.

Returning to college, Fleming was determined to reinvent himself as a scholar—to replace illiteracy with mastery over language, to go from being ignored and unseen to commanding attention. He immersed himself in the work of Black thinkers from the Harlem Renaissance to present day. Crucially, he found debate, which became the means by which he transformed his life and the tool he would use to transform the lives of others—teaching underserved kids to be intrusive in places that are not inclusive, eventually at Harvard University, where he would make champions and history.

Through his personal narrative, readers witness Fleming’s transformation, self-education, and how he takes what he learns about words and power to help others like himself. Miseducated is an honest memoir about resilience, visibility, role models, and overcoming all expectations.

Genre:

-

“Miseducated is a stunningly crafted book exploring the radical possibilities of what happens when a Black child who ‘hates’ school finds the language, tones, and practice to contextualize and precisely state why he rightfully resents the parts of American formal education system that hated him. In that way, the book is not so much about a prelapsarian kind of renewal, but a full hearted conjuring of an equitable future. I learned how to learn and how to teach again in Miseducated. This is breathtaking art and heart work.”Kiese Laymon, New York Times bestselling author of Heavy: An American Memoir

-

"Miseducated touched my soul. From the very first sentence to the last, I was riveted. Only one other book has affected my soul so profoundly. It was my great-great grandfather’s Narrative – and, fatefully, the book that happened to change Brandon’s life."Nettie Washington Douglass, great-great granddaughter of Frederick Douglass, great-granddaughter of Booker T. Washington, Cofounder & Chairwoman of Frederick Douglass Family Initiatives

-

"Though we frequently hear about the disproportionate numbers of Black boys and men who struggle in school and experience incarceration, narratives that provide perspective-shifting insight into the beautiful humanity of these boys and men are few and far between. It is impossible to read this book and not come away with a combination of fury over the oppressive systems that miseducate, and faith in the power and resilience of the human spirit to overcome. Miseducated is vital reading as we fight our way to a more equitable world."Nic Stone, #1 New York Times bestselling author of Dear Martin

-

"Despite seemingly insurmountable barriers standing in his way, Brandon P. Fleming reinvented himself in similar ways as the Black scholars who shaped him. Frederick Douglass, beginning his quest for literacy, 'set out with high hope, and a fixed purpose, at whatever cost of trouble,' and Fleming, consciously continuing Douglass’s tradition in Black autobiography, likewise set out to learn and eventually teach and inspire a new generation of black thinkers. Inspiring, heartbreaking and gripping, Miseducated is pure motivation."Tripp Rebrovick, PhD, Director of Debate, Harvard University

-

"Miseducated breaks your heart and then heals your soul with the love and agency of an educator who never stopped believing in himself. This is a beautifully written, deeply moving portrait of a vulnerable and tender Black man who uses his sheer strength and stamina to not only save his own life, but also the lives of his students living in a country that has put a target on their bodies, minds, and souls. Brandon P. Fleming dares us to see him and his students as anything other than human. This is what we mean when we say Black Lives Matter."Candacy Taylor, award-winning author of the bestselling book, Overground Railroad: The Green Book and the Roots of Black Travel in America

-

"Spellbinding storytelling...With immediacy and stylistic flair, Fleming powerfully narrates his difficult childhood with an absent mother and a violent stepfather; his total-immersion course in street life and failure in school; a chance at a Division I basketball career that he would have destroyed himself if injury had not beat him there; a dramatic incident of lust, infidelity, and an attempt at murderous revenge that occurred when the author was only 14; and his interest in—and great talent for—debate, which turned out to be one of the most transformative elements of his life....Informed by the autobiographies of Malcolm X and Frederick Douglass, the books that finally overcame his resistance to reading, Fleming adds a compelling chapter to the body of literature that inspired him. An inspiring page-turner for all readers, especially those seeking to overcome significant obstacles to find success."Kirkus Reviews

-

“Fleming gives us an intimate look at his transformation from a troubled youth to an esteemed scholar and educator in this intimate memoir….The author is candid about the pain he experienced….His recollections of debate tournaments are a highlight of the memoir, showing the moments in which he discovered the power of his voice and connecting with others….[A] story about triumph of the will. Fleming conveys his passion for learning and teaching, in writing that is by turns entertaining and moving. This is a must-read for educators, as a professional development tool and to consider for high school curricula.”Library Journal

-

"[A] bracingly frank [memoir] about his phoenix-like rise from a violent, abusive home on the margins and his wayward stint on the streets as a drug dealer[,] with... gritty details and feel-good ending."Atlanta Journal-Constitution

-

"[A] fascinating and inspiring memoir."Arab News

- On Sale

- Jun 14, 2022

- Page Count

- 272 pages

- Publisher

- Hachette Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780306925146

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use